In recent decades, Quebec scholars have paid special attention to the américanité of French Canadians—the extent to which they have been culturally, economically, and politically American, whether they be on Canadian soil or in the United States. This conceptual lens has proven its worth not merely in studies of recent Quebec history. When projected over nearly two and a half centuries of North American history, it reveals a fascination with (and ambivalent response to) American political ideals. In time, the lure of republicanism would yield to cultural and economic concerns, but, in the 1830s, reformers and radicals in Lower Canada could envision a day when they too would break free from colonial bondage and more fully realize democratic ideals.

~ ~ ~

From the beginning of the American Revolution, political ideology played a major part in the relationship that bound French Canadians to their southern neighbours. The Patriot invasion and occupation of the “Old” Province of Quebec in 1775-1776 opened new possibilities for those living under British rule. Although this incursion never elicited a sustained mass uprising of French Canadians, anti-colonial and republican promises no doubt influenced men like Clément Gosselin and Basile Mignault as they joined the revolutionary endeavour.

The impact of these ideals was not confined to immediate contemporaries of the War of Independence. In the 1820s and 1830s, as uncompromising attitudes led to near-permanent conflict between the predominantly French-Canadian legislative assembly and the British colonial administration in Lower Canada, political grievances cohered as an ideology inspired by the American revolutionary experience and the United States’ democratic institutions.

Finding their agenda blocked by the appointed Legislative Council, the Parti Patriote sought to reform the upper chamber along democratic lines. In the face of British intransigence, the opposition disrupted the business of government—halting appropriations for the colony’s infrastructure, schools, public health measures, the salaries of civil servants, and more—to obtain concessions. Reformers and radicals promoted non-importation, as American revolutionaries had.

A commission of enquiry led by Lord Gosford failed to report favourably on the Patriotes’ democratizing agenda; after its recommendations became the policy of John Russell’s government in Britain, mass rallies became common occurrences in the Lower Canadian countryside. Public order broke down, to which colonial authorities responded by revoking militia commissions and issuing arrest warrants in cases of sedition. The formation of the American-inspired Fils de la liberté in the summer of 1837 was emblematic of the moment. A few months later, a full-scale revolt was at hand—although here the rallying cry could not be “no taxation without representation.”

Nevertheless, in 1837 and through the following winter, when a small band of exiled insurgents formulated their own declaration of independence, the Patriotes envisioned a polity that would recall the United States in most respects.

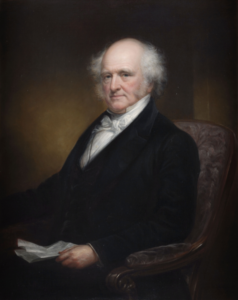

In their campaign to rid the continent of British power, the rebels won the approval of American public opinion. But the hoped-for support of the United States’ federal government never came. President Martin Van Buren’s administration, certain Democratic officials, and the Whig Party in particular were eager to avoid conflict with Britain so soon after the War of 1812, from which neither country had gained much. Both the United States and Britain were contending with the aftershocks of the Panic of 1837; both were concerned with other foreign policy challenges. Lord Durham, governor of the British colonies in 1838, stated in his famous report that there had never been “a time in which the specific relations of the two countries rendered it less likely that the United States would imagine that a war with England could promote their own interests.”

With American accomplices, some exiled rebels launched attacks on Canadian soil from the perceived safety of U.S. soil, an episode of Canada–U.S. history known as the Patriot War. In response, Van Buren enforced a reinvigorated Neutrality Act and dispatched military forces to the border—not to intimidate Britain, but not restrain raids into Canadian territory. As this article at Borealia explains, the mutual interests of peace won the day. After the failed invasions of 1775 and 1813, there would be no new attempt to seize British North America. The larger benefits of friendly bilateral relations in effect deprived the Patriotes of a republican state in which French Canadians would hold the reins of government.

In fact, high-ranking British officials rejected the notion that the Canadiens could ever become Americans in any genuine sense. Durham exclaimed that

[t]here is no people in the world so little likely as that of the United States to sympathize with the real feelings and policy of the French Canadians; no people so little likely to share in their anxiety to preserve ancient and barbarous laws, and to check the industry and improvement of their country, in order to gratify some idle and narrow notion of a petty and visionary nationality.

Durham identified a clash of values between dominant races, with French Canadians on one side and the Anglo-American world on the other. Although the former had their virtues, the governor stated that they were “not so civilized, so energetic, or so money-making a race as that by which they are surrounded.” As we will see in a future post, Henry David Thoreau would come to a similar conclusion about a decade later, but all the while envisioning republican possibilities that Durham could not.

And yet, hundreds of thousands of Canadiens did enjoy the republican promise, ironically thanks to friendly Anglo-American relations as well as continental economic integration. They did so as migrants. “[T]he stationary habits and local attachments of the French Canadians render it little likely that they will quit their country in great numbers,” Durham wrote. He was, in this respect if not others, wrong. In the second half of the nineteenth century, as the Catholic clergy and political elites pushed the Rebellions to the margins of Lower Canada’s self-conception, French-Canadian migrants asserted the right to maintain their inherited cultural identity while embracing the political values and institutions of the Great Republic. The Canadiens could be committed republican citizens. But that dream would be fulfilled on American soil, not in Canada.

In an upcoming instalment, we will look at economic relations between French Canadians and the Great Republic in the decades leading up to the American Civil War. Stay tuned!

Further reading

A synopsis of the international ramifications of the Canadian Rebellions, with special emphasis on the Patriot War, is available from the International History Review.

Gérard Bouchard and Yvan Lamonde’s Québécois et Américains (1995) offers a valuable introduction to the question of américanité. On early-nineteenth-century American influence and ideas of liberty, see Louis-Georges Harvey, Le Printemps de l’Amérique française (2005), and Michel Ducharme, The Idea of Liberty in Canada During the Age of Atlantic Revolutions (2014). Also keep an eye out for Maxime Dagenais and Julien Mauduit’s forthcoming The Canadian Rebellion and Jacksonian America (2018), an edited collection discussing some of the same themes. The excerpts of Lord Durham’s Report are taken from Gerald M. Craig’s edited version (1968).

At last, Mark Paul Richard provides robust analysis of the relative Americanization of Franco-Americans in Loyal But French: The Negotiation of Identity by French-Canadian Descendants in the United States (2008).

Leave a Reply