Last month, we revisited one of our recurring characters in light of new archival evidence. This post also brings us to Vermont, but it takes us away from politics and away from archives as we usually imagine them.

Our “guest” did not have the name recognition that J. D. Bachand enjoyed in his day. He is not a minor historical celebrity. His name may no less ring a bell. In the spring of 2018, I contributed an article titled “Au revoir, Jerry” to Le Forum; a translated version has since appeared on this blog. The title character was Jerry Cross, born Jean Baptiste Jérémie Lacroix in the Township of Brome, Lower Canada, in 1855. He was a brother to my great-, great-grandfather, Edouard Lacroix.

My interest in “uncle” Jerry’s life did not stem from the reverential filial piety that long drove genealogical research, though empathy there certainly was and is. I find in his life the type of microhistory that can sometimes be just as revealing as sweeping, ambitious works about an entire society. It is a story of immigration and industrialization, a story of poverty and persistence in little-studied areas. It is also a story where things don’t go according to plan.

A quick refresher: Jerry migrated to Vermont as a young man. There he met and married Sophie Brosseau, a companion for forty years. Sophie experienced at least fifteen pregnancies, but of the live children only six reached adulthood. The rate at which the family lost children—not counting stillbirths—exceeded nineteenth-century averages, perhaps a sign of their material circumstances. The family lived in Fairfax in the 1870s and 1880s, after which they lived in various Franklin County and Northeast Kingdom towns in quick succession: St. Albans, Swanton, Lowell, Irasburg, Coventry. We have no evidence, at present, that they ever owned land outright. At some point, after 1910, the family splintered. Jerry lived with a son in Connecticut at the time of the First World War. But he was back in northern Vermont, on his own, in the winter of 1918. Months later, he decided to take his own life.

The questions are many. What explains the struggle to secure and pay off a plot of land? Would the Crosses have fared better north of the border? Did Jerry’s wife and children abandon him? Was he a deadbeat or a drunk? How did his adoptive communities view him and his family?

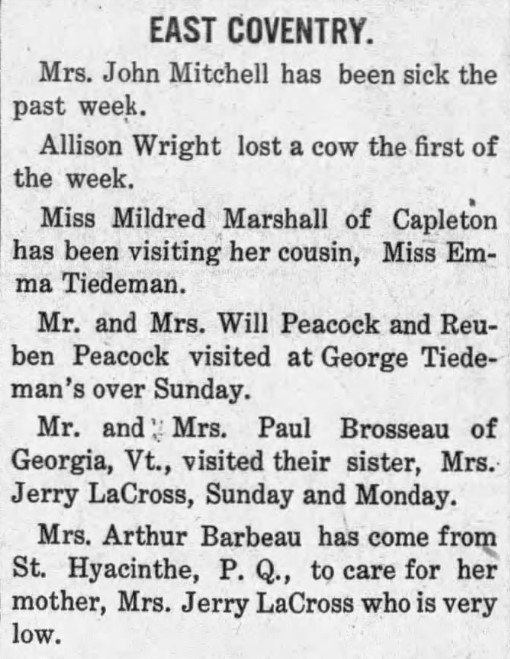

The story is made more complicated by a slightly cryptic social note published in the Orleans County Monitor in March 1907. “Jerry Cross,” it reads, “has moved from the [Irasburg] town farm.” As I found in my travels in northern Vermont, town farms, or poor farms, are no longer remembered even in the communities that hosted them. We might think of these farms as a temporary employment program and as one of the few ways of dispensing charity before the state and federal governments introduced a social safety net. The “deserving” poor would pay for their room and board by contributing to the publicly-owned farm according to their skills and mental and physical abilities, though, in some places, people with major disabilities were supported for the long term. Generally, local taxpayers did not want to see the town farm incur a deficit that they would have to make up. That helped determine who might be selected, not that anyone truly wished to be on the dole (or on the farm). This was a last resort that no doubt injured the pride of those who had nowhere else to go—and that provides a sorry glimpse into the Crosses’ circumstances in the first decade of the twentieth century.

To learn more about these reluctant charity cases, I turned to the town clerks of Lowell and Irasburg. From a look at these towns’ vaults, I began to appreciate how many small, local gold mines of information—barely explored by historians—lay across the Green Mountain State.

I had visited Lowell, Vermont, before; a number of times, actually. On one of those visits, helped by a local cemetery volunteer, I had visited the small unmarked stone that gives Jerry’s final resting place. No one had stepped forward to pay for an inscription. Jerry was condemned to oblivion outside of the memories of the living. The town office offered Chapter 2 in the mysterious case of the vanishing Crosses. The imposing cabinet holding genealogist Betty Kelley’s research files on local residents includes a folder on the Cross family—a folder that lay sadly empty, as if to acknowledge that they existed but no more. It held not a single note. As with the grave marker, memory and erasure cohabitated a little too comfortably.

The meticulous recordkeeping of former town officials saved me. Municipal log books reveal that Jerry and Sophie settled in Lowell in 1899. They sought to purchase a large plot of land, including an entire surveyor’s lot, along with its cattle, farm implements, vehicles, and crops, from one Frank W. Jordan. The family had evidently saved up to make initial payments towards the ultimate sum of $2,550. Three years later, they relinquished their claim and the farm returned to Jordan. It is likely that they could no longer make payments. “Mr. Cross is undecided as yet what he will do,” a paper indicated.

There were other sources of income beyond the farm, local road maintenance for instance. Jerry received $27.05 from the Town of Lowell for road work in 1904. But these paltry sums did little for the family’s long-term prospects.

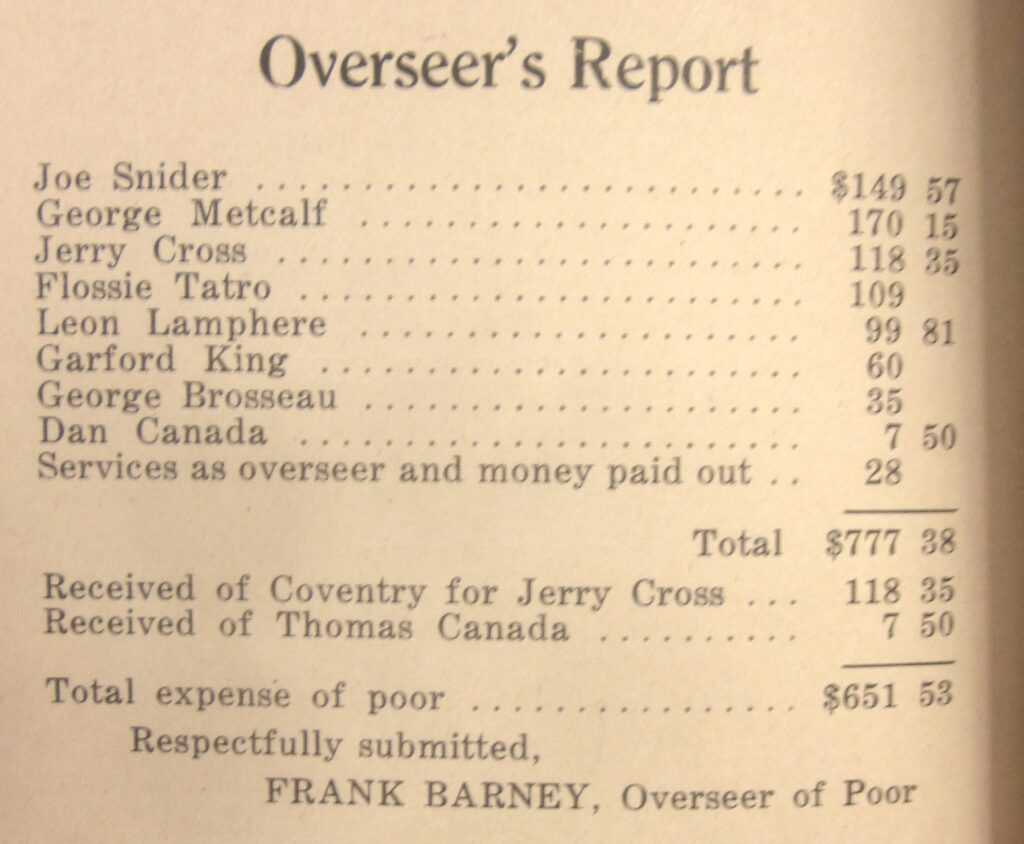

Records of disbursements for road work tell us that the Crosses did not leave Lowell upon losing their farm and that Jerry was still able-bodied enough to provide (some) physical labor. In or about 1905, the family disappear from local town records, having likely moved to neighboring Irasburg. In 1906-1907, the Overseer of the Poor—who also served as superintendent of the poor farm—in Irasburg recorded payments totaling approximately $80.00 to the family.

The family’s admission to the town farm hints at their “worthiness” of charity. The proceedings of Lowell town meetings explicitly state that local selectmen and residents left matters of charity to the discretion of their own Overseer. It seems Irasburg functioned similarly. There is no evidence that locals publicly discussed whether Jerry, Sophie, and their children ought to be admitted to the farm. The decision lay in one elected official’s hands—and that decision momentarily saved them. That probably wouldn’t have happened had Jerry been deemed shiftless or a helpless alcoholic.

The town farm was a temporary shelter; it did not change the Crosses’ circumstances. Newspaper articles reveal repeated moves from 1907 to 1912. It is possible that one of their daughters took Sophie in when she fell ill in 1912. That would explain why the couple was estranged in 1918.

Jerry went to live with a son, Fred, who worked in a textile mill in Danielson, Connecticut. As noted above, he was back in northern Vermont in the winter of 1918. Again, local town records fill the gaps. We know that Jerry was living with the Bousquet family in Lowell when he committed suicide. The municipal treasurer’s cash book recorded payments totaling $54 for Euphémie Laferrière (Mrs. Omer Bousquet) on order from the local Overseer of the Poor. It seems incontrovertible that these payments were for Jerry’s care. The town’s Grand List for 1918 states that Jerry had no real or personal property; he was a pauper and a marginal note (“sickness”) provides context.

Yet the story is again complicated by evidence that Lowell received payments from the nearby town of Coventry to provide for Jerry’s care. We can afford a few conjectures. Jerry and Sophie’s youngest surviving son, George, and his wife Loretta lived in Coventry in the 1910s. Ill and perhaps requiring care, Jerry would have left Connecticut and perhaps stayed with George, though that arrangement would have been short-lived. It seems he qualified for assistance in Coventry, but it may be that there was no home that could welcome or accommodate him. The next best option lay with the Bousquets in Lowell and so one town simply paid the other. At least for the second time in his life, Jerry was “on the dole,” though this time not on a poor farm—and quite explicitly because he was sick. Those two facts, and the sense that he was a burden, bring us to the decision that brought it all to an end, tragically, in 1918.

In many respects, Vermont towns continue to operate as they did more than a century ago. March meetings are an important affair where essential business is transacted. The idea of small, local, grassroots, and inexpensive government survives. Clerks are the face (and the sinew) of many towns. But changes in the management of the social safety net with increasing state and federal involvement have enabled us to forget what charity existed prior to the 1960s. Payments made by a local Overseer of the Poor and the charity dispensed through town farms have slipped out of the collective historical consciousness.

Ethnicity does not seem to have entered the equation. The sheer number of French Canadians in northern Vermont, some of whom were entering positions of public trust, negated the issue to an extent. But, amid the temptation to celebrate better, simpler days, it might do us well to remember the harsher edges of a society that, despite its efforts to care, modestly, for those who struggled, could be unforgiving and leave some of its members behind.

Leave a Reply