Mention race and the conversation to follow may prove to be a powder keg. Some folks are likely to bring up (with contempt) woke ideology and critical race theory; others, systemic racism and persistent inequities. These issues are political, as they should be, politics being the space where we discuss society-wide issues to find solutions, often at the cost of compromise (l’art du possible). There are different kinds of politics, however, and healthy, civil, constructive exchanges around racial equity seem all too rare.

These conversations tend to be more difficult when they involve white minority groups and their historical relationship to the native-born white majority and to people of color. This is partly due to the “in-between” space that white immigrants and their descendants occupied in the American ethnic and racial landscape. They faced discrimination and contempt while enjoying opportunities inaccessible to African Americans, Asian Americans, Indigenous peoples, and other groups. The point of establishing a wider racial context is not to engage in “oppression olympics,” as one friend very aptly calls this type of conversation. Rather, it is to historicize present circumstances in hopes of fostering a better understanding of ourselves and others.

Almost from the moment of arrival in the United States, white immigrant groups were status-conscious. Facing discrimination and competing for economic advancement, they sought to sort out their place in U.S. society. French Canadians were among these groups. We have abundant research on the hostility that Franco-Americans encountered, but only in the last decade have scholars connected these experiences with the field of race studies. Historians have asked whether (or to what extent) Franco-Americans were themselves racialized during the era of mass migration and how they found their place in a society marked by profound inequities.

Immigrants and their descendants often responded to that discrimination by doubling down on their whiteness and meeting Anglo-Saxon racial criteria. They intended to fit in—and fit within the dominant group. As a result, over time, status anxiety helped harden American racial lines. Immigrants were also concerned about property values, employment, and “unfair” comparisons that would set back their acceptance by mainstream society. Franco-Americans were not immune to this process.

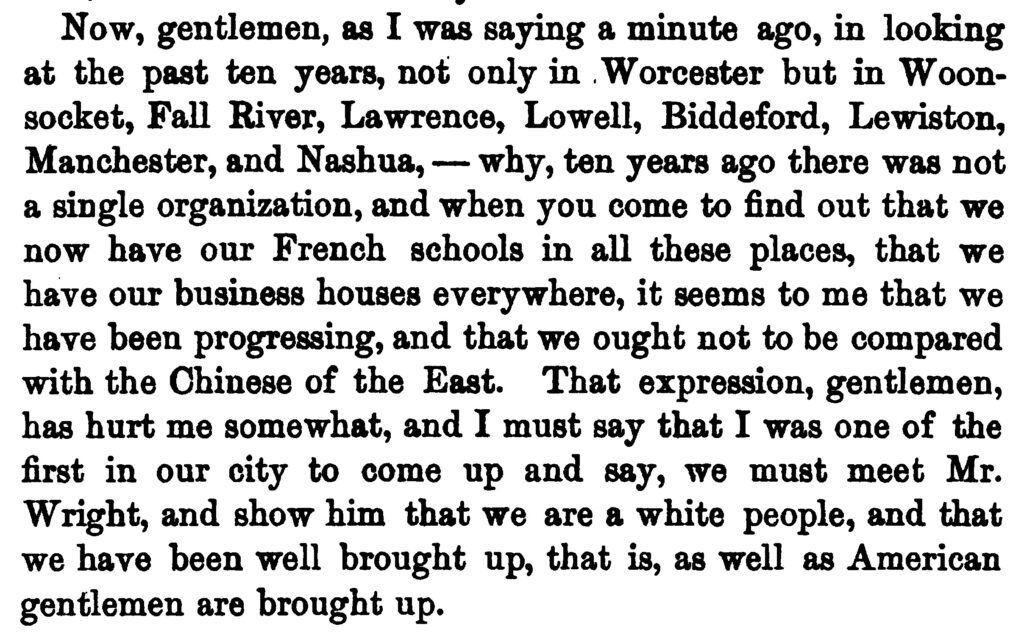

Reactions to the infamous “Chinese of the East” report were telling in this respect. Franco-American elites were emphatic in denouncing the comparison to a far more marginalized people—so marginalized that they were the first singled out for immigration restriction. The reaction among French Canadians was not an outburst of solidarity with East Asian immigrants; the French were among civilized nations and this was considered a slur.

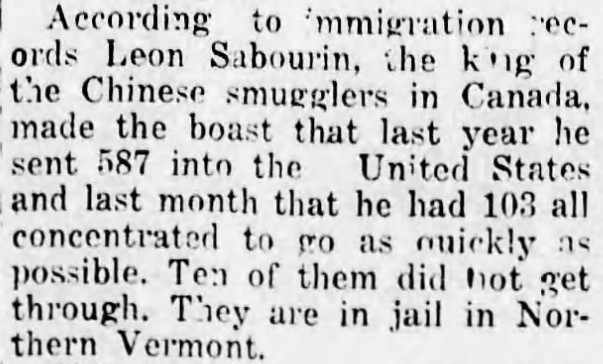

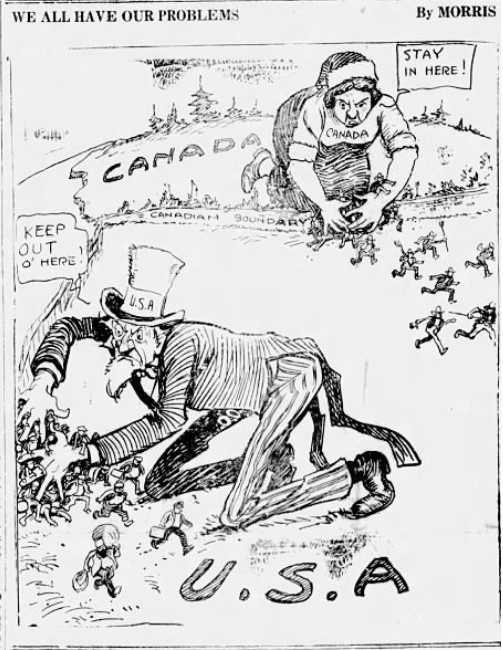

The different fates of Franco-Americans and visible minorities became particularly clear in the involvement of French Canadians in the “smuggling” of Chinese migrants across the northern border during the 1920s. We should not confuse this with the complicity of an entire people, but the nature of human trafficking reflected the widely different circumstances of the two groups in the United States (in Canada, too, actually).

The same process of cultural and racial distancing involved other groups. While today many people of French-Canadian ancestry seek out and embrace possible Native roots, this was not always the case. As several historians have argued, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the French-Canadian intelligentsia followed Pascal Poirier and went out of its way to refute theories of widespread intermarriage between French settlers and Indigenous people. School children were taught damaging and outright racist tropes about the First Nations. Poirier himself insisted on the purity of French blood, which had the dubious virtue of connecting French Canada to the achievements of a world power and dismissing as less civilized the Indigenous peoples of America. (Lionel Groulx also insisted on French-Canadian purity and homogeneity.)

Outright racism thrived in other settings, including minstrel shows held in Little Canadas all over the Northeast over the course of generations—into the late 1950s and perhaps later. Blackface performances turned African Americans into objects of ridicule. They established a clear color line—and clearly established where Franco-Americans stood. These shows also pointed to Franco-Americans’ gradual adaptation to mainstream culture, as they accepted and consumed forms of entertainment that were widely enjoyed by white audiences in the host society. We should not think that this was a passive curiosity. The historical record is clear: such events were organized by and held in Franco-American parishes, often with entirely French-heritage casts.

People of French-Canadian descent had it far from made on U.S. soil—this too is clear. But there was another side to their in-betweenness: that they fit the rubric of “free white persons” under U.S. naturalization law seems to have been seldom contested. Nativists often indirectly conceded that French Canadians, under slightly different institutions, could assimilate. If they abandoned their ancestral language, foreswore the Church of Rome, and accepted the ways of the majority, they might well become indistinguishable from other (white) Americans. In fact, Franco-Americans had the luxury and privilege of becoming invisible—though that would come at the cost of a culture that had its own legitimacy and that had anchored them for generations. To be sure, well-placed people expressed graver and darker doubts about Francos in the era of Social Darwinism—all while these Francos reached unprecedented influence and occupied public spaces as never before.

Again, contrary to a certain narrative, this type of research is not an act of liberal self-flagellation, or yet finger-pointing meant to single out Franco-Americans. For one thing, similar processes have been identified in other white ethnic groups and in the WASP mainstream. Nor is the point to make anyone feel better or worse. It is a matter of using the past to understand the present and bring perspective to current issues, particularly the long-term construction of racial identity and race relations in this country. It helps us see how marginalized groups have historically sought to shed their outsider status. Avoiding the kneejerk “pas nous autres,” it is in fact possible to accept the historical record, lean into discomfort, and think of how this speaks to the present. Just as earlier generations of Franco-Americans were agents (not unconstrained, but agents nonetheless) of their own circumstances, so are we. Research of this kind reminds us that we should feel empowered to engage with issues whose fruits will be felt for generations to come.

You can find more information on Franco-Americans’ adaptation to the United States’ ethnic and racial landscape in the latest issue of the Journal of History.

Leave a Reply