Some four years ago I completed a draft of my “COVID book,” which would be published as “Tout nous serait possible”: Une histoire politique des Franco-Américains, 1874-1945, the first full-length regional synthesis of Franco-Americans’ political involvement.

The book is available in French only, though many aspects have appeared in similar form on this blog since its inception. Last year I shared a translated excerpt on the struggle to create and mobilize a French-Canadian electorate in Connecticut. This time, in appreciation of those who have followed and supported Query the Past, I am pleased to share another excerpt of the book—one that takes us farther north. We pick up the story in New Hampshire and Vermont in the 1910s.

Please cite appropriately.

* * *

Eight months after the election of Charles Lemaire in Lewiston [1917], grocer Moïse Verrette won a strong majority over the incumbent mayor of Manchester, Republican Harry W. Spaulding. He was not the first “Franco” to try his luck. Alderman Victor W. Roy, a Republican, had run for office in 1912. However, it was Verrette, five years later, who became the city’s first Franco-American mayor. Like Lemaire, Verrette was re-elected at the height of One Hundred Percent Americanism. Other challenges appeared. His second swearing-in took place at home since he was suffering from severe rheumatism. The following month, his continued absence from city hall was drawing attention. In June 1920, aldermen claimed – without mentioning his health – that Verrette was unable to fulfill his responsibilities and should resign. He chose not to run again in 1921 – not without condemning a campaign of slander waged against him. Beyond the city’s budgetary challenges, his long absences may have prevented him from cultivating political connections that could benefit his career. Several Franco-American mayors would follow him in Manchester.

Nashua followed the example of its sister-city by appointing local lawyer Henri A. Burque as mayor on December 2, 1919. Burque had completed his elementary education at the French parish school before pursuing a classical course in Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir, Quebec, and then in Montreal. He had served as city attorney and clerk of the State Senate prior to his election; he also participated in Nashua’s Franco-American social and cultural life. In 1924, following his second term as mayor, Democratic Governor Fred Brown appointed Burque a judge of the New Hampshire Superior Court. As in Manchester, Franco-American mayors followed, including the young attorney Alvin Lucier in the 1930s.

Beyond the industrial centers of Manchester and Nashua, reports from the interwar period attest to the extensive Franco-American presence in town halls across New Hampshire and the numerous state legislators sent to Concord. Franco-Americans represented Newmarket; the manufacturing towns located on the Cocheco and Salmon Falls rivers (Rochester, Somersworth, Rollinsford, and Dover); Keene and Claremont in the western part of the state; Franklin and Laconia in the center; and, of course, Berlin. The local elections of March 13, 1923 were particularly promising at the state level. “In Newmarket,” one report read, “Mr. Joseph Rousseau was elected municipal clerk; Mr. Wilfrid Laporte, selectman for three years; Mr. Arthur Labranche, treasurer; Mr. Alexandre Pelletier, commissioner of public works.” . . .

At the state level, the political position of Franco-American voters was always more complicated. In the 1950s, political scientist Duane Lockard highlighted the strong majorities that the Democratic Party achieved in manufacturing centers where the “Francos” were concentrated, particularly Berlin, Manchester, Nashua, and Somersworth. This trend was already apparent in the interwar period. However, two factors prevented this ethnic influence from breaking into the state’s highest executive positions. First, the Democratic Party was continually plagued by a lack of cooperation between its French and Irish factions. Only one Democrat, Fred Brown, succeeded in becoming governor during the interwar period; he won his race perhaps because he was a “Yankee” who did not arouse the resentment of either the Irish or the Franco-Americans. Second, especially in the era of Republican Styles Bridges, who served as governor and then senator, Democratic leaders often abandoned their party to accept a sinecure granted by the GOP. . . .

Franco-American voters might win state nominations and carry their own to certain positions of influence, but the obstacles were always lower and fewer at the local level. In 1928, Eli King (of Berlin) and Pierre Gagné were defeated as candidates for the state executive council, but a former senator from Manchester, Democrat Cyprien J. Bélanger, won a seat. The following year, Bélanger chose to run for mayor of Manchester. He therefore faced another Franco-American, Arthur E. Moreau, who was seeking a third term. Moreau, a Republican, won the fight. He was undoubtedly helped by his reputation, his experience, and the search for steady hands in the first weeks of the economic crisis. Dr. Damase Caron, a Democrat, won a landslide victory over Moreau in 1931, a time of growing poverty in the manufacturing centers. In his day, Moreau was perhaps the most prominent Franco-American Republican in New Hampshire. He served twice as one of his party’s four presidential electors for the state. But, outside of local races, the Democrats generally had the support of “Francos,” especially from 1930 onwards. Thus, Henri Ledoux of Nashua, a candidate for governor in 1932, was more representative of the leanings of his compatriots than Moreau (it is also difficult to imagine the nomination of a Franco-American gubernatorial candidate by the Republican Party). We might also think of attorney Fortunat Normandin of Laconia, whom the Democratic caucus selected as minority leader in the state’s lower house in the 1940s.

In Vermont, Franco-American figures remained visible in the civic affairs of Burlington and Winooski after the Great War. Republicans retained their majority on the Burlington city council. However, the city often gave a majority to Democratic candidates for mayor. The Franco-American electorate contributed to this trend. Initially inclined to follow manufacturing interests in politics, these voters gradually turned to the Democrats. According to a study dating from the 1930s, the electoral participation rate of “Francos” lagged behind other ethnic groups’ involvement, but their geographical concentration on both sides of downtown Burlington, particularly in the industrial Lakeside neighborhood, regularly secured for them two or three of the twelve council seats, which roughly matched their share of the city’s total population.

The neighboring town of Winooski formally separated from Colchester in 1922, cementing the distinct interests (urban and industrial, rural and agricultural) of the two sections of the former municipality of Colchester. In Winooski, the Franco-American element found itself represented in innumerable public service positions; “Francos” also held elective positions. Clerk Joseph Cauchon oversaw the first municipal election, in 1922 – an election in which several Franco-Americans competed for council seats. Among these candidates was F. Edward Allard, the Democrat whose political engagement spanned more than twenty years. Allard’s rise continued: in 1925, minus the two votes received by one Ruth McArthur, Allard was elected mayor by acclamation. He returned to power and served two more one-year terms at the end of the decade.

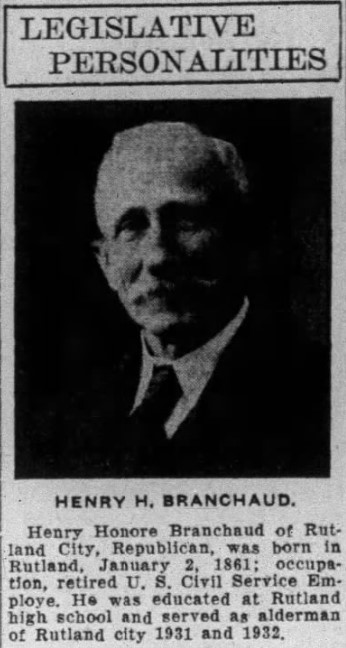

The Franco-American presence in civic positions elsewhere in Vermont did not quite reach the level it enjoyed in Burlington and Winooski. However, after the First World War, members of the community held positions of public trust in small centers such as Montgomery and Lowell, and then in small cities such as Rutland, Barre, and St. Johnsbury. In Rutland, Henri Branchaud gained local influence before winning a seat in the State House; he supported the GOP, which alone could ensure his political rise. Born in the United States, Branchaud had not abandoned his cultural heritage: he helped organize the Rutland Congress in 1886, took part in his local Saint-Jean-Baptiste society and co-founded, at the beginning of the twentieth century, a Canadian-American Club. During the tercentenary celebrations of the “discovery” of Lake Champlain in 1909, he participated in a banquet in Vergennes. The press published his reflections on the French history of the region, which he had been unable to deliver for lack of time. Branchaud then enjoyed a career as a postal clerk on the region’s trains. Following his retirement, he entered politics in his hometown of Rutland. In September 1932, he secured one of the Republican nominations for county senator in the legislature – which guaranteed him victory in the general election. In 1935, he won the mayoralty in a three-way race.

The following year, it was the Franco-American electorate of Barre, a granite-producing center, which asserted itself in politics. In an issue of Le Travailleur that called for Ferdinand Gagnon to be honored with a statue, a correspondent reported on ethnic assertion now occurring in Vermont. Wilfrid Beaulieu had founded this newspaper in Worcester five years earlier and loudly preached the ideology of survivance. He was no doubt pleased to share the news of a national awakening in the Green Mountain State. The correspondent, signing “Ludger Duvernay,” reported on a meeting of around 200 “Francos” that had taken place in Barre in October 1936. Speakers A. C. Archambault and J.-Louis Boucher had encouraged the individuals in attendance to become citizens and registered voters. According to “Duvernay,” this gathering was national (ethnic) in nature. Boucher declared that “[f]or the first time in the history of Barre, Franco-Americans are actively involved in politics.” This involvement, necessary “for us to be recognized,” would only occur by voting “as a bloc.” Boucher added: “We have all complained quite often that nothing or almost nothing had been done for Franco-Americans; we heard that so-and-so had not been treated fairly; for example, our Franco-American workers have difficulty obtaining building permits, our truckers have difficulty getting employed by the city, again and again!”

Thus, by becoming more involved in politics, the Franco-American population would no longer have to suffer from discriminatory decisions. The politics of their new homeland would enable the minority to better protect its cultural identity and its rights.

“Duvernay” noted the presence at this assembly of a candidate ready to hear the “Francos” and to represent them – it was obvious that the block vote that Boucher hoped for should mobilize for this candidate. But this person was not Franco-American and, although the correspondence published by Le Travailleur did not mention it, the event was in reality partisan. The guest of honor at Scampini Hall, among these hundreds of French-speaking voters, was Deane Davis – a former judge and, now, the Republican candidate to represent the town of Barre in the Vermont State Assembly. Introduced by lawyer Reginald T. Abare, Davis alluded to the French and American traditions of political freedom. He insisted on the danger presented by a powerful, increasingly centralized government. Dr. Archambault was more precise in attacking Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, particularly in relation to its cost. Davis may have courted the “Francos” and insinuated himself into their good graces with a few words of clumsy French, but it was as much a question of public policy and ideology as it was of ethnic recognition. It was in vain: a few weeks later, Democrat John A. Gordon defeated Davis.

In the wake of Branchaud’s election in Rutland and the growing political movement in Barre, another pivotal moment awaited the Franco-American population of Vermont. This also occurred through the cogs of the state’s Republican machine. In 1937, dentist Joseph Denonville Bachand became president of the Commission on Foreign and Domestic Commerce, the highest position until then occupied by a “Franco” in Vermont government.

* * *

We will have more on Bachand in an upcoming post. Until then, check out these other posts on political topics:

Leave a Reply