An earlier version of this essay appeared in Le Forum, vol. 39, no. 3 (fall 2017), 3-5. See the full original version here.

How knowledgeable are you of Franco-American history? What about your fellow Americans, or your fellow Canadians—how conversant are they? Unfortunately, many Americans of French descent know little about their heritage; it is even more problematic that a great proportion of historians and history teachers on both sides of the border overlook Franco-Americans. This suggests that now, perhaps more than ever, it is imperative that we elicit general interest in our field, both in and out of the classroom.

Even with David Vermette’s new tome on the subject, few monographs with a primary focus on Franco-Americans have appeared in the last fifteen years. But, in that time, at least seventeen master’s and doctoral theses have been completed and, every year, peer-reviewed journals carry articles with a focus on this very topic. Thus, even if we recognize that scholarship on Franco-Americans has lost vigor since the now-fabled Institut français colloquia of the 1980s and 1990s, the field still has its specialists who are pushing the bounds of research. The last biennial conference of the American Council for Quebec Studies makes this plain as indeed will the organization’s upcoming meeting in New Orleans. If Franco-Americans remain on the margins of our historical consciousness as a society, then, the issue may be one of communication. A cursory look at this ethnic group in the context of American and Canadian history will underscore the magnitude of the challenge still ahead.

Those of us who have taught U.S. history at the high school or college level are woefully aware of Franco-Americans’ invisibility in standard, commercially available textbooks. But insofar as textbooks reflect the broader landscape of research, this should come as no surprise. Whereas the Irish, Germans, Italians, and other ethnic groups are favored examples, Franco-Americans are regularly omitted from survey works on immigration, acculturation, and related matters. The rare book on New England, or on a specific state’s history, will often make passing but unsatisfactory references to the French-Canadian migrants and their descendants.

The field and sub-fields of Canadian history are—naturally, perhaps—more attentive to those who migrated to Canada than to those who left. But, no matter their perspective, historians of Quebec do typically recognize those emigrants who settled in the U.S. Northeast by the hundreds of thousands.[1] The demographic hemorrhage that shook the province transformed its social and economic landscape and elicited consternation, to put it mildly, among policymakers and social elites. Appropriately, this migration marked the historical record.[2]

But is the history of Franco-Americans really just an extension of Canadian history? There is a case to be made for it: in Little Canadas across New England, from Woonsocket to Waterville, the immigrants formed national parishes, spoke their native tongue, practiced their ancestral customs, read French-language newspapers, and patronized Canadian-owned businesses—as they had north of the border. The ethnic neighborhoods were, in fact, termed “colonies” at the time, a hint of the providential and quasi-imperial mission that certain elites assigned to these immigrants.

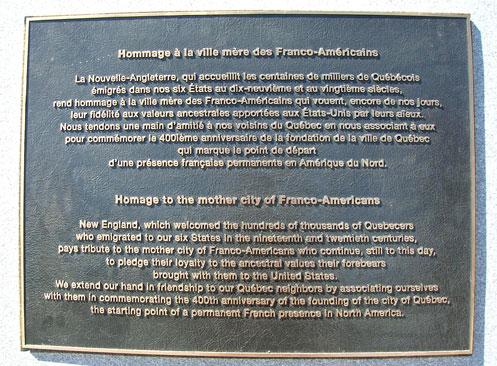

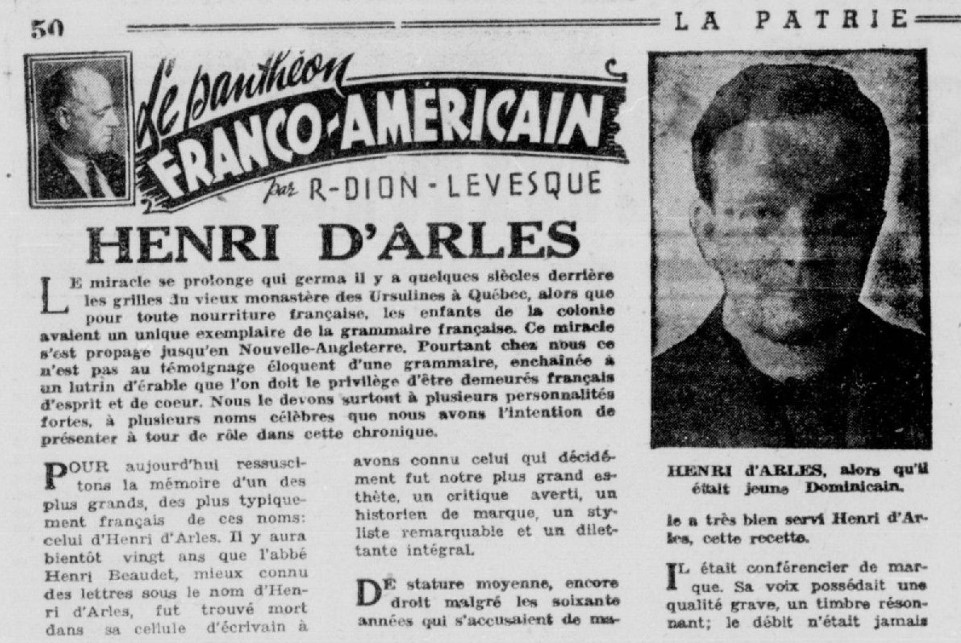

The francophone community built astride the Canada–U.S. border began to fracture in the 1910s and 1920s. But the exiled sons and daughters of Quebec were not entirely forgotten. Although less regularly, Quebec newspapers continued to carry items from Franco-American communities. From 1950 to 1956, La Patrie, a Montreal daily, carried Rosaire Dion-Lévesque’s Silhouettes franco-américaines, a weekly column on illustrious francophones in the United States. Franco-Americans concerned about their survivance watched intently the hatching and tribulations of neo-nationalism and separatism in the “old country.” At the end of the century, as academic colloquia drew Quebec researchers to New England in great numbers, older Quebeckers still remembered visiting American cousins as children. At last, the Franco-American Monument dedicated by then-Premier Jean Charest and guests in Sillery, in 2008, seems to regard the grande saignée and its cultural legacy as extensions of Canadian or Quebec history.[3] The dedication ceremony, held in connection with the four-hundredth anniversary of the founding of Quebec City, highlighted renewed willingness to view the emigrants not as traitors, but exporters of a larger cultural universe. Recent events show that New England’s Franco-American heritage has become the basis for closer relations between Northeastern states and Quebec.[4]

Alas, few histories of Quebec are so thorough as to describe the fate of the expatriates as they navigated their American setting—their circumstances once settled in the United States. Franco-American studies are, by their very nature, partly Quebec history, but historians of Quebec have in this respect offered Franco-Americans limited attention. It is hardly surprising. Even as scholars have analyzed the province’s américanité, they have recognized that these expatriates and their descendants became Franco-Americans.

The question of whether Franco-American history properly belongs to Canadian or American national history may be unfair, for Franco-Americans very often fell under both designations. It was, after all, the assertion of community leaders in Little Canadas across New England, at the dawn of the twentieth century, that the immigrants could be proud and loyal American citizens while remaining faithful to the culture of their ancestors. Appropriately, transnational history has sought to do justice to these distinct but overlapping identities and to the porosity of political boundaries. This conceptual approach helps us explore linkages and phenomena that can easily remain hidden in the “either/or” of national history.

We can and should develop this transnational perspective to its fullest extent, as some historians have recently sought to do.[5] As teachers, however, we must still place our field within the bounds of national history, which remains the framework for most high school and college curricula. As scholars, we must still be attentive to the way we engage with other researchers—which sometimes means accepting their paradigms—when asserting the significance of Franco-American history. In this respect, two points deserve special mention.

I would first suggest that we take care not to overemphasize the uniqueness of Franco-Americans’ experience. Their story is connected, for instance, to the realities of European immigration that John Bodnar has ably described. The French-Canadian diaspora fits neatly within a pattern of economic upheaval, tied to new capitalist practices and agricultural consolidation, that affected much of the Western world through the nineteenth century.[6] At the same time, their story is relevant in the context of a larger continental history whose boundaries have been contested down to the present. Scholars of Franco-American history have ample opportunity to relate their findings to the transnational experience of Mexicans and other Hispanic peoples in the American Southwest.[7] In short, we can assert the relevance of our field by engaging more deeply in comparative history.

Second, Franco-Americans matter on a larger tableau. It often appears as though the late nineteenth-century ethnic ghetto has been replicated in research—scholars insulating themselves and addressing only fellow Francos or those working in the same field. But this perspective tends to take it as an essential premise that French-Canadian immigrants were invisible and on the margins of society, as though the points of intersection with the American mainstream (however defined) were long negligible. But the immigrants and their descendants were never invisible. They disturbed and disrupted the existing order of Quebec by leaving and that of New England by settling. And they engaged. They altered the landscape of culture, labor, politics, and religion in the U.S. Northeast, not to mention its urban geography. They were noticed and at times resented by other groups.[8] Having focused intently on mill life, family structures, the ethnic parish, the French-language newspaper, and mutual benefit societies, the scholarly community still has much to do to fully represent larger patterns of engagement with the host society.

No doubt I am singing to the choir. In fact, there are superb teachers and scholars throughout New England and beyond—many of whom will read this—who understand the importance of bringing Franco-American studies into the classroom and engaging with non-academics. But I would insist particularly on the need to engage differently with other scholars in our research endeavors—or engage with different scholars. How often do we reach out to those who do not specialize in Franco-American history? Do we encourage comparative work, participate in more ecumenical conferences, or submit to publications where Franco-Americans would otherwise seldom appear? Here, “publish or perish” takes on new meaning. If we don’t publish in these wider forums, our field and our historical subjects will disappear from view entirely—relegated to historical obscurity.

For more than a century, there has been ceaseless hand-wringing over the fate of Franco-Americans, especially with regard to the survival of their culture and language. Underlying this fear has been a sense of French-Canadian exceptionalism—that this group was not destined to be melted into the great American pot as the Irish, Germans, Italians were. I do not suggest that historiographical hand-wringing is necessary. But I would underscore the need to normalize Franco-Americans, eagerly placing them alongside other immigrant groups and asserting their equal significance in the arc of modern American history.

[1] I leave the matter of Acadian history and scholarship to those who may more expertly write on the subject. I also hasten to add that English Canada experienced a wave of emigration to the United States similar in size to Quebec’s francophone exodus between 1870 and 1930. See Randy William Widdis, With Scarcely a Ripple: Anglo-Canadian Migration into the United States and Western Canada, 1880-1920 (1998).

[2] The large-scale expatriation of French Canadians is noted in every major survey of Quebec history, not least as evidence of a long-term, structural economic transformation, but also for the domestic social and political consequences it entailed. This migratory movement is mentioned in the Quebec government’s pedagogical guidelines for the province’s high school curriculum.

[3] Albert J. Marceau, “The Three Franco-American Monuments in the Promenade Champlain, Quebec,” Le Forum, 34, 4 (Spring 2010), 13-15.

[4] I have considered this issue here and here.

[5] In regard to Franco-Americans, one of the most prominent examples is Yukari Takai’s Gendered Passages: French-Canadian Migration to Lowell, Massachusetts, 1900-1920 (2008).

[6] Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (1985). Bruno Ramirez has drawn on these connections in his On the Move: French-Canadian and Italian Migrants in the North Atlantic Economy, 1860-1914 (1991).

[7] See George J. Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (1993).

[8] See, in this regard, Mark Paul Richard, Not a Catholic Nation: The Ku Klux Klan Confronts New England in the 1920s (2015), which places Franco-Americans within a larger context of nativism and cultural chauvinism.

Leave a Reply