Last week’s blog post quoted Grégoire Chabot on a hypothetical Franco-American “hall of fame.” Chabot seemed to find few worthy models. Yet, surely, if Francos are to recognize the accomplishments of their community, they ought to find important and influential figures in their past. What famous individuals has the community produced? Who are its leading lights? Its bottom-of-the-ninth batters? Who has proven to be an exceptional model among Francos and the object of admiration among other Americans?

I have often heard and read the view that Franco-Americans have not received the historical attention that their numbers would warrant, especially as compared to Irish, Italian, and Jewish Americans, people of Hispanic heritage, and so on. I think there is something to that. There is cause to feel worse if Francos do not have a commensurate number of historical “all-stars,” or famous individuals of the same caliber as those of other cultures.

The issue is not that illustrious Francos worthy of attention are nonexistent. Many are simply still relegated to blind spots in our historical consciousness. Historians—of which I am one—deserve some blame for failing to highlight the great impact of Franco-American figures and to bring them into mainstream culture.

There is another, more insidious problem: for generations, the community has contended with a very narrow definition of that which makes a Franco-American. Some elites, past and present, have promoted a purism in regard to religion, language, and culture… such that an individual who does not check a certain number of boxes may as well be a traitor—and ought to be confined to obscurity. That view has trickled down, as it does in many ethnic groups. One wants visibility and recognition for the group, but may have second thoughts if one of their own draws too far from a prescriptive identity.

Thus, in the last century and a half, the Franco-American pantheon has evolved only to a point. In the 1870s and 1880s, French-Canadian immigrants celebrated la Saint-Jean-Baptiste under banners honoring two revolutionary figures: the Marquis de Lafayette and Louis-Joseph Papineau. Although both figures spent time on U.S. soil, neither was a Franco in any meaningful sense of the word. At this time, it simply made sense for immigrants to claim recognition and respect by identifying themselves with famous French figures. They also emphasized the role of the French explorers who had preceded the English in parts of North America that eventually became the United States.

During the first half of the twentieth century, there were Franco-Americans to celebrate, notably Ferdinand Gagnon (“the father of the Franco-American press”) and such political figures as Edmond Mallet (a Civil War hero and senior civil servant), Hugo Dubuque (a Massachusetts legislator and State Superior Court judge), and Aram Pothier (a six-term governor of Rhode Island), with some occasional acknowledgment of Los Angeles mayors Damien Marchessault and Prudent Beaudry. Soon enough Francos could claim to be represented in the Catholic Church’s hierarchy with Bishop George Albert Guertin.

Meanwhile there were “adoptive” Francos, those occupying an in-between position for spending only part of their lives on U.S. soil. Singer Emma Albani, editor and politician Honoré Beaugrand, Alfred Bessette (Frère André), strongman Louis Cyr, and “O Canada” composer Calixa Lavallée ultimately proved of greater consequence in the writing of Quebec history. At the other end of the spectrum, the likes of Robert Desty and, later, Margaret Chase Smith have been deemed too assimilated to be invited into the pantheon.

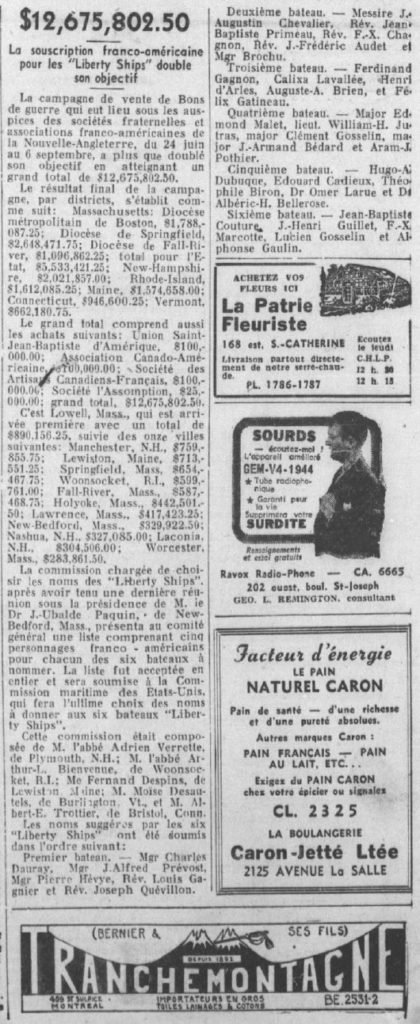

During the Second World War, Franco-American leaders issued a report proposing names for Liberty Ships that would honor men—indeed, all individuals proposed were men—from their community. The figures chosen by the committee again reflected a very clear, and narrow, “type”: Roman Catholic, French-speaking and bearing an unadulterated French name, involved in the cause of survivance, with the majority being either a priest, an editor, a physician, or an attorney (liberal professions traditionally favored in Quebec).

As well as the individuals mentioned above, the committee included people of more local fame: Omer LaRue of Connecticut, J.-B. Couture of Maine, and J.-H. Guillet of Massachusetts. It is also noteworthy that they began their list of nominees with the builders of Franco-American religious institutions—fathers Dauray, Hevey, Chevalier, and Primeau, particularly.

Individuals involved with the recent Sentinelle crisis were in a sense expunged from the honor roll. So was Charles Chiniquy, the Catholic priest who, after drawing thousands of French Canadians to Illinois, renounced his faith and became a leading Presbyterian. Popular entertainers like Eva Tanguay were definitely out. We can imagine that baseball players Leo Durocher and Nap Lajoie were held in high regard by Franco-American sports fans. At last, whereas crooner Rudy Vallee apparently did not merit a Liberty Ship, he was likely the most famous Franco of his day in mainstream American culture.

The end of the war brought temporary fame to Manchester’s René Gagnon, who helped to raise the American flag at Iwo Jima.

Since then, the temple de la renommée has been considerably enriched by Jack Kerouac and Grace Metalious. But, a generation after their deaths, Chabot could quip that only Robert Goulet remained among living Franco celebrities. With Goulet now dead for over a decade, I would suggest that we are down to E. J. Dionne. Of prominent politicians of French-Canadian ancestry, former governor Paul LePage of Maine has been the most explicit in expressing a personal connection to the culture.

In 2001, a work titled Making It in America: A Sourcebook on Eminent Ethnic Americans provided the names of ten individuals of French-Canadian descent: two members of the Aubuchon family (of hardware store fame), author Robert Cormier, Sentinelliste Elphège Daignault, Jack Kerouac, Edmond Mallet, Aram Pothier, Claire Quintal, and Adolphe Robert and his son Gérald-Jacques. The dean of the Franco-American press in the second half of the twentieth century, the editor of Le Travailleur for nearly five decades, Wilfrid Beaulieu, would have been a natural fit in this group.

The characters chosen for Making It in America show a loosening of the bounds of Franco-America—at last we have business people and a famous figure of dissent. But business people and inventors (Cyprien Odilon Mailloux, Louis Goddu) are still routinely overlooked, perhaps because they operated in predominantly Anglo-Protestant circles. Historian Barry Rodrigue has made a compelling case for approaching industrialist Tom Plant as a Franco-American figure; his work might provide guidance in bringing such figures into the limelight.

Clergymen of consequence are plentiful—we might even count the current archbishop of Quebec, who was educated in Manchester—but what about Protestant Franco-Americans like the Baptist proselytizer Narcisse Cyr? And, by the way, as Chabot also pointed out, where are all of the women? Beyond Claire Quintal, Camille Lessard-Bissonnette and Yvonne LeMaître merit greater recognition, but so do dozens of other female figures.

Contemporary playwrights and creative writers (Normand Beaupré, Grégoire Chabot, Rhea Côté Robbins, David Plante, Robert Perreault), poets (Paul Marion, Steven Riel), and entertainers (Josée Vachon), as well as illustrating the rich culture of French-Canadian descendants, may yet enter a wider, American “hall of fame” as their influence continues to grow beyond the Franco-American community.

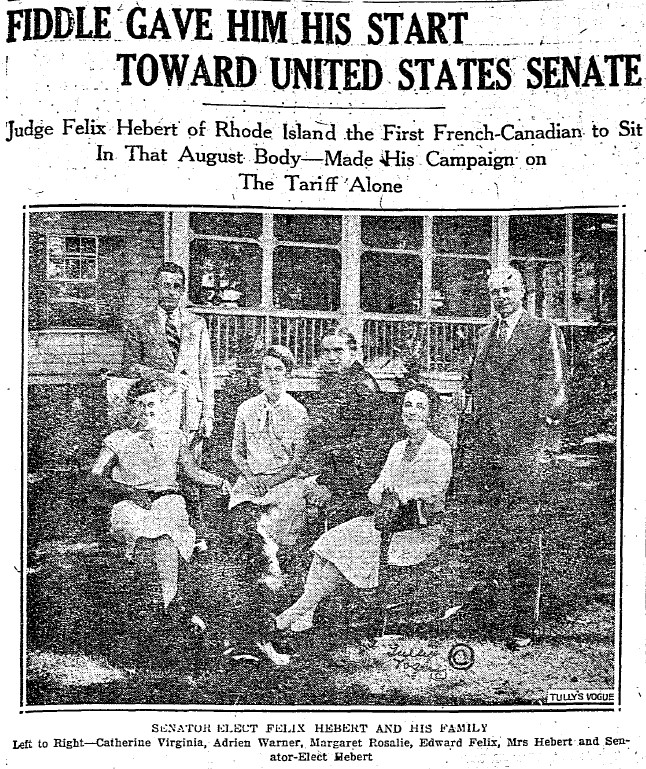

But this lies beyond the scope of this historian’s work. At present, there is a great deal more to do to resurrect prominent Francos and an important case in point lies in politics. I hope to eventually provide more information on the hundreds of Francos who entered elective office in the first half of the twentieth century. For the moment, I would note Felix Hebert, a native of Quebec, a U.S. senator from Rhode Island in the early part of the Great Depression (1929-1935), and Rudolph Roulier, also a native of Quebec, the longest-serving mayor of Cohoes, New York (1940-1959). Both were recognized as French Canadians by the mainstream press and earned kudos as such. They represent the tip of an iceberg of distinguished personalities that deserve the attention of present-day Francos and other Americans.

Please note that any omission here is not meant to be disparaging—no such text could be exhaustive. The Franco-American Hall of Fame in Maine and the several organizations that present a “Franco-American of the Year” award attest to the many Francos who continue to make a difference in their communities.

I’m an advocate for inclusive Halls of Fame – for example, I would enshrine Dwight Evans for baseball and the J. Geils Band for rock. On topic – I’d add more more inventor/business types: John Garand of rifle fame and Joe Coulombe (the founder of Trader Joes) are two national figures. Paul and Gerald D’Amour of the Big Y Supermarkets are more regional.. A worthy successor to Louis Cyr in the strongman tradition is Paul Levesque, better known as WWE wrestler Triple-H. If we extend membership to those who are half-Franco, runner Joan Benoit Samuelson and singer/actress Madonna are high profile women who add prestige to any Hall of Fame. Ray Bourque, the legendary Bruins defenseman became a naturalized US citizen in 1996, he’s in. If we are willing to stretch for long-time resident aliens (and I would), Celine Dion is in as well.

Many thanks for sharing your thoughts, Dan. All great contenders!

The American-French Genealogical Society of Woonsocket, Rhode Island established a French Canadian Hall of Fame in 2003 as part of the org’s 25th Anniversary celebration. https://afgs.org/site/hall-of-fame/ While a significant portion of these HOFs have a Rhode Island connection, RI residence is not a requirement.

Thank you for sharing this, Rick. So many distinguished Francos!

I am building a list of 5,000+ French heritage women…and more to go…so I think the oversights are difficult to explain. Are the women hidden, forgotten or more to the point, ignored. FAWI and the courses I designed/taught for U/Maine, Orono…were just a starting line…