Dueling Francos

The battles were over. The fighting had ceased. But, while men might lay down their arms, often the war does not leave them. Trauma is not easily cast aside; invisible wounds remain.

By 1792, the French-Canadian veterans of the Continental Army had not seen a battlefield in over a decade. But since those years of struggle, they and their families—who had spent years in refugee camps—had been hardened by a different kind of fight.

Some had acceded to New York State’s apparent generosity and accepted lands on the western shore of Lake Champlain. Something of a small community developed around la rivière Chazy, north of present-day Plattsburgh.

Though Indigenous bands had inhabited the region, this was for all intents and purposes a complete wilderness to the Canadiens. They had to clear the land over the course of successive summers while they depended on meager rations authorized by Congress. When women and children were finally brought up to the settlement, they grew potatoes and turnips between the stumps. They grew hungry. They were cold. And they suffered the abuse of British forces that remained on Lake Champlain after the treaty of 1783.

Hunger, isolation, and fear do things to a person. So, whatever the actual facts of the matter, what happened near la rivière Chazy in 1792 demands no great explanation.

The story goes something like this.

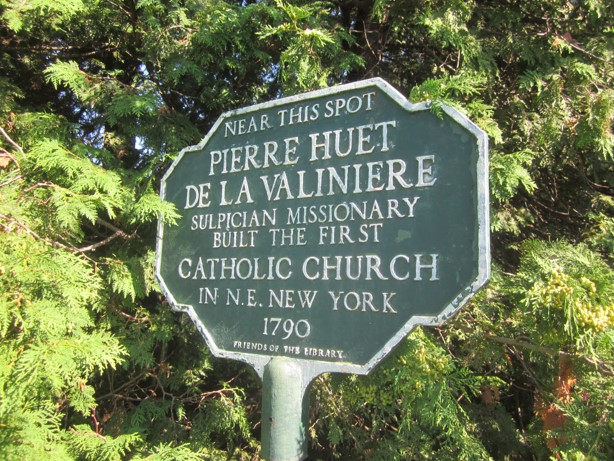

Even as improvements to the land were made after 1786, tensions remained high. The small Catholic chapel was burned under suspicious circumstances and the pro-American prelate was driven off. At that time, veteran Jacques Rouse was militia captain of Clinton County (the northeastern corner of the state) and could not escape the infighting and injuries.

Mid-afternoon, on the last day of August 1792, Rouse visited Peter Janqueray and, sword in hand, declared, “How do you do, Mr. Janqueray, I call to see you. I cannot live any longer unconcerned with you. I am full of grief that, so few Frenchmen as we are here, we cannot live in concord together.” Janqueray replied that the settlers couldn’t help it. Angrily, Rouse stated that Janqueray was speaking ill of him every day, which his counterpart denied.

The arrival of another veteran, Louis Marnay, in the midst of the conversation did not calm Rouse.

According to the captain, Janqueray had said that he, Rouse, wasn’t a man—that he was a coward. The sword on his side suggested that he intended to do something about the allegations and to prove his manly mettle.

Janqueray would argue before a grand jury that this was attempted murder, but Rouse was very clear in challenging him to a fight, which Janqueray declined.

The conversation meandered until Rouse complained about business dealings involving Janqueray’s partner, Peter Dubree, and he threatened to deal with both with “the end of [his] sword.” Janqueray declined the challenge again, Marnay went away, and Rouse ranted on with “things unworthy to be inserted” in subsequent court proceedings.

That the challenge to a duel did eventually land before a grand jury should not hide the fact that this was largely an institutional wilderness—an area without schools, constables, and structures of control and compulsion, unless we count the heavy-handed British garrison that added to the anxiety. We should not wonder that Rouse took matters into his own hands, that in light of his past he acted rashly.

Hunger, isolation, and fear do things to a person.

Or is it that we are uninclined to wonder because even in the lap of comfort we too have wished to pay a visit to those who would speak ill of us?

* * *

First it was the young men who left their homes. They found work on the docks and in the fields. Like their forebears, some fought in American wars. They faced the enemy in Veracruz and Virginia.

Then there were women and children. And communities, and churches, and schools, and hopes.

It wasn’t long until there were publishers, pundits, and opinionmakers.

By the mid-1870s, a century after French Canadians encountered “Americans” on their soil, something called Franco-America was cohering in the northeastern United States. But community formation and institutional consolidation did not entail perfect unity. From Quebec, the migrants imported longstanding divisions in their midst. So, what happened in December 1875 should come as no great surprise.

The story goes something like this.

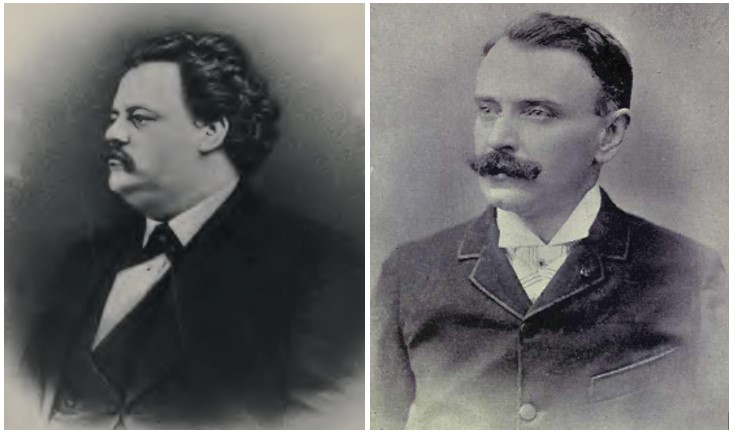

Until the end of the century, all years were lean years for the French-language press in the Northeast. The few editors competed with one another for intellectual influence and financial viability. No conflict was more bitter than that between Ferdinand Gagnon in Worcester and Honoré Beaugrand in Fall River.

Three basic facts about Gagnon are especially well-known.

He died young.

Intellectually and professionally, he was a larger-than-life figure.

And he was quite simply… large.

Beaugrand would later win acclaim as the author of Jeanne la Fileuse and win the mayoralty of Montreal. In 1875, he was a middling editor reputed to be a freethinker, in contrast to the ultramontane Gagnon.

Tensions rose as invective gradually escalated and, at last, Beaugrand called his counterpart a hypocrite in the pages of his paper. Cleverly, Gagnon replied that Beaugrand could use his trowel—a reference to freemasonry—to sling mud all he wanted, he, Gagnon, was done with character assassination.

But Beaugrand wasn’t done. He claimed that an infantry regiment could use Gagnon, by virtue of his incredible girth, as target practice at a mile’s distance. Children ran away in fear when Gagnon walked down the street, he stated, for monsieur croquemitaine would not hesitate to eat them.

Beaugrand ended his letter with cryptic words that seemed to invite Gagnon to a duel. The latter responded that this was below him, and in any event he had three baptized children to provide for.

Both men dropped the matter afterwards. Ultimately, then, theirs had been a duel of the pen and neither had to explain himself to a grand jury.

Hunger will do things to a person, not just physical hunger, but a craving for influence, attention, recognition.

That is true of all times; there were trolls and boasters long before there were social media, blogs, podcasts, and Zoom… And in all times, there have been men eager to defend their honor with sword or pen.

The two vignettes are drawn from the Moorsfield Antiquarian (1.2) and the Revue franco-américaine (7.3). Check back in next week for the conclusion.

Leave a Reply