While at the Quebec Studies colloquium at Bishop’s University, last spring, I introduced part of my research on French Canadians and Franco-Americans in geographical margins—areas usually overlooked by scholars. What do we really know about French-Canadian immigrants and their descendants outside of Lewiston, Manchester, Lowell, Fall River, and the likes? Local historians have done tremendous work in unearthing and preserving their communities’ past, but relatively little of their efforts has trickled into larger narratives about the Franco-American experience. Researchers need to pay closer attention to the ethnic communities of northern New York; Barre, Vermont; Exeter, Somersworth, and Berlin, New Hampshire; and many other locations.

My statistical study covers the northern half of New York State (as a whole, often ignored by scholars of Franco-American history) and all of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. I have omitted three counties—Hillsborough, New Hampshire, and Androscoggin and York, Maine—precisely because they were larger centers of Franco population and I wish to delineate what happened beyond. Those three counties include Manchester and Nashua, Lewiston–Auburn, and Biddeford–Saco, which have been the subject of intensive study.

This large area at the northeastern end of the United States, contiguous with Quebec and New Brunswick, stretches from Syracuse, New York, to the Aroostook region and Passamaquoddy Bay. In the second half of the nineteenth century and early parts of the twentieth century, it offered a cultural and economic landscape altogether different than did the massive industrial cities mentioned above. For one thing, work in textile manufacturing plants was much less central to the Franco experience; agriculture, skilled trades, resource extraction like the lumber industry, and other, smaller manufacturing opportunities were just as likely to occupy immigrants from Canada and their children. Further, whereas in large cities the ethnic landscape was often extremely diverse and fractured, in my survey area French Canadians were by far the largest and most noticeable foreign-language minority.

Census returns reveal a geographically extensive presence throughout the period generally associated with the grande saignée, 1840 to 1930. Clusters are nevertheless discernible in all four states. From my regional sample, the top counties in sheer number of French Canadians born abroad were as follows in 1900: (I have included leading towns and cities to help situate readers less familiar with the region)

- Strafford (Rochester, Somersworth), N.H., 5,180

- Coos (Berlin), N.H., 4,683

- Merrimack (Concord), N.H., 4,490

- Kennebec (Augusta, Waterville), Me., 4,174

- Chittenden (Burlington, Winooski), Vt., 3,680

- Albany (Cohoes, Troy), N.Y., 3,626

- Clinton (Champlain, Plattsburgh), N.Y., 3,213

- Cumberland (Brunswick, Westbrook), Me., 3,180

- Franklin (Malone), N.Y., 3,081

- St. Lawrence (Massena, Ogdensburg), N.Y., 3,035

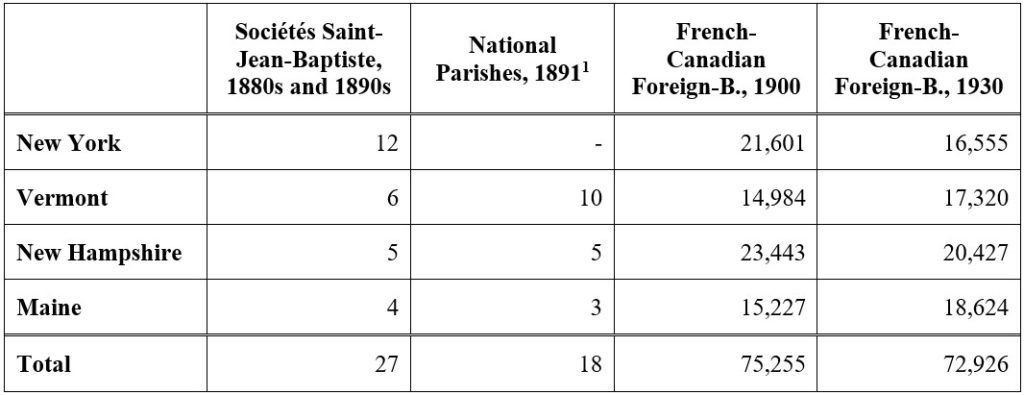

The chart below provides a sense of the significance of the foreign-born population in 1900 and 1930. To show that this was not merely a dispersed population meant to quickly disappear into the American melting pot, I have also included indicators of community formation for the 1880s and 1890s. Even in less densely populated parts of northern New York and northern New England, French Canadians banded together, established sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste, and obtained Catholic national parishes. (Many more local organizations and national or mixed parishes appeared after 1891.)

Despite the apparent decline in population in the last two columns, in most places the Franco-American population grew over time, even while some families did return to Canada after a short stay in the United States. By 1930, there was a much larger proportion of French Canadians born on U.S. soil in many of the counties (a demographic not captured in the table above). There were then fifteen counties each with more than 5,000 French-Canadian individuals either born in Canada or in the U.S. to Canadian immigrants.

But the point of this research is not merely to emphasize the statistical significance (and larger relevance) of “migrants on the margins,” even if much more work must be done in this direction. A county-by-county approach focusing on economic hinterlands is necessary if we are to properly capture shifting patterns of settlement over time.

Thus far, it is apparent that nearly all counties in New York State experienced an absolute loss in people born in French Canada from 1900 to 1930—one major exception being Onondaga County, which includes Syracuse. In other words, New York receded as a major destination of French-Canadian immigration after the turn of the century. In Vermont, we find major increases in counties adjacent to Quebec, as well as in the areas around Barre–Montpelier and St. Johnsbury, but a decline in Rutland County. For the same period, there were increases in Coos and Sullivan counties in New Hampshire, but dips elsewhere, including in Merrimack County, just north of Manchester. At last, outside of the Lewiston and Biddeford areas, Maine provides a mixed picture: growth in Oxford County (which buttresses New Hampshire and includes Rumford) as well as in Somerset and Kennebec, with relative stability elsewhere.

By looking more intently at this broad region of the U.S. Northeast, it is also possible to identify distinct subregions, understand their economic structure, and connect them through chain migration to regions of Quebec and New Brunswick. Beyond statistical studies, it will be necessary to plunge into local histories, patch them together, and better understand the interethnic relations and socioeconomic characteristics of the local Franco-American population. Perhaps the ultimate pay-off will be a greater sense of how survivance and acculturation occur, or yet what it has meant, historically, to be a Franco-American outside of the well-established and well-known Little Canadas. Either way, y’a d’la job en masse. Join me!

[1] My source for national parishes, Fr. Edouard Hamon’s contemporary study of Franco-American life, did not explicitly identify New York Catholic churches as national, mixed, or other. Nor did Hamon provide names and locations for twelve ethnic parishes in the Madawaska region of Maine, which accordingly do not appear in this table.

Leave a Reply