One of my most challenging moments as a teacher occurred ten years ago, when, as a fresh-faced teaching assistant at Brock University, I was leading a seminar on the Holocaust. Among my students was an Indigenous girl who eagerly raised her hand to make—quite tangentially—a comparison between Nazi-led ethnic cleansing and the historical experience of the First Nations in Canada.

The comparison caught me off guard. I didn’t know how to respond, how to move forward with our agenda without brushing off the painful history that prompted this comment—I wanted to acknowledge it and put it to didactic use, but I did not know how.

The problem was partly in me and in my own inexperience. But it was also in the comparison.

Both examples pointed to a long history of oppression. But the connection was tenuous and the unique historical experience of each of these two groups (European Jews and First Nations) was lost in the comparison. Those were the pedagogical challenges; more difficult yet was the task of addressing this student’s “we had it just as bad.”

The temptation to make comparisons to other historically marginalized people is always present for minority groups, especially those whose story has yet to be fully told. To gain legitimacy, or recognition, or some form of reparation, it seems necessary to say, “you have acknowledged this other group’s struggles; we had it just as bad.”

Franco-Americans have not been immune to that temptation. Now, for the record, I have never heard anyone compare Franco-Americans’ historical experience to that of European Jews or Indigenous peoples; the Francos I meet, and have met, are animated by good faith and intellectual honesty. Further, the present reflection was sparked by a comment posted online by someone I do not know.

I concede that this is never a good starting place. But the comment, which needs no advertising here, does suggest that concepts of race, ethnicity, and whiteness have become murkier over time. They have proven especially complicated with regard to people of European descent (including French Canadians) who, in the United States, faced nativism and prejudice while often reaping the “wages of whiteness.” (More on this last point below.)

To put it differently, in the late nineteenth-century, French-Canadian immigrants were, like other ostensibly white groups, assigned a racial essence by theorists and national mythmakers. Each national group had its own inherent characteristics, it seemed. There was a great deal of ambiguity as to whether, being genetic, these traits were forever present in a people and could only be diluted, or, through education and moral instruction, the same traits could be “ironed out” over the course of a few generations. Regardless, most ethnic groups that entered the U.S. between the Civil War and the 1920s were deemed inferior to white American Protestants of Anglo-Saxon “stock.”

Most people in the Northeast who fit this mold, or who had ascended to a position of privilege (like the Irish), needed no lofty theory to resent the Canadians’ presence. Conflict erupted over local bread-and-butter issues, including pew rents and strikes. But the theories were there.

So, what’s this business about wages of whiteness? To be quite blunt, French Canadians were neither Black nor Asian and that served them well. There was cultural separateness, but no separate lunch counters and water fountains. There was pain and strife, but certainly not the deep scars of family separation and violence inherited from slavery times. There were street fights, but no lynchings. We know it instinctively: if living in 1870, which group would you rather belong to?

It can be argued (as David Vermette has[1]) that in the view of Progressive-Era racial theorists, people of French-Canadian descent did not meet a certain standard of whiteness. That is still quite different from arguing that Franco-Americans were people of color or visible minorities. (“Not fully white” is a figure of speech.)

Although Francos were subaltern and social, political, and economic ascent could be very difficult, it was possible to move up, especially from a multigenerational perspective.

Unfortunately, Pierre Vallières’ Nègres blancs d’Amérique (translated as White N——s of America) and other works have allowed extremely dubious comparisons between the historical experience of Franco-Americans and that of visible minorities. Such comparisons are unhelpful besides a larger point that we already understand: there is a long history of oppression.

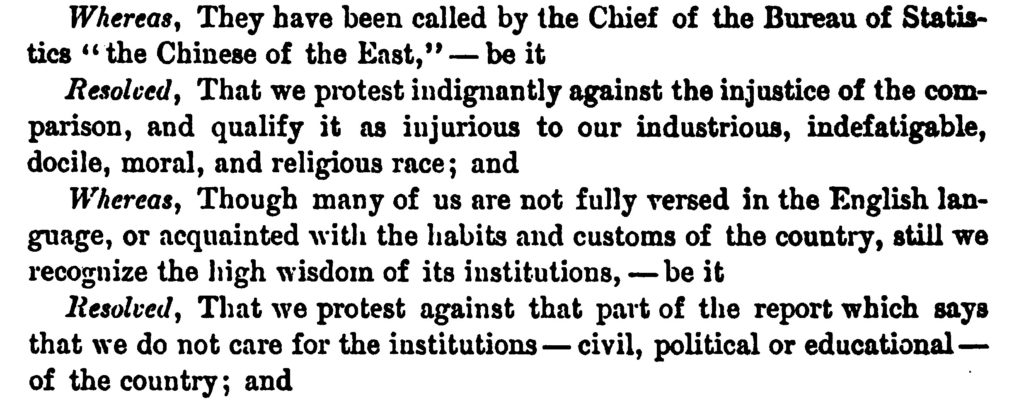

The problem of asserting one’s legitimacy while subaltern (or marginalized) without making light of others’ own struggles is longstanding. It has often made for historical moments we would prefer to forget. Quebec-born Robert Desty easily joined the campaign against Chinese immigration while working as an attorney in California, for instance. It is also worth remembering the racial dimension of Colonel Wright’s most infamous report, in which he deemed Francos the “Chinese of the Eastern States.” It was a slur—and it was taken as a slur by French Canadians in the U.S. And what are we to make of the Franco-Vermonters who attended blackface performances and, worse yet, were cast in local minstrel shows?

At last, the white ethnic revival of the late 1960s and 1970s was not a haphazard occurrence. It began as a white reaction to the African-American civil rights movement particularly as it began trickling up to northern cities. This “revival” was not entirely ill-intentioned; social justice was in the air and here was an opportunity for minority groups to claim their long-awaited place in the sun. Many finally felt empowered to vigorously defend their right to their ancestral culture. Alas—and here I’m not writing specifically about evidence from Franco-American communities—we don’t have to scratch very far to find the proverbial “we had it just as bad.”

The point is not that Franco-Americans have a less rosy history than other groups or that racism was (or is) at the heart of their self-definition. Of course not.

I am however suggesting that, whatever racial theories were in vogue a century ago, we cannot today compare Franco-Americans to visible minorities in any meaningful way—least of all to gain legitimacy.[2]

As for French Canadians’ status between the Civil War and the 1920s (and arguably long after), I still prefer David Roediger’s term: “inbetweens.” These immigrants’ place in American society varied from one county to the next all depending on local conditions. They were viewed differently by working-class Irish families and by “old-stock” Yankees. Sometimes they were seen as unassimilable; sometimes their culture and heritage made them perfectly suited to the duties of U.S. citizenship. Across the board, however, they were constantly in between.

[1] David and I sometimes arrive at different interpretations and conclusions, but by no means do I dispute the evidence he quite compellingly lays out in A Distinct Alien Race.

[2] As I see it, the type of work seen in Jill M. Bystydzienski’s “Minority Women of North America: A Comparison of French-Canadian and Afro-American Women,” published in the American Review of Canadian Studies (1985), makes a different kind of connection. Bystydzienski places each group in its specific historical context and, cautiously avoiding generalizations, advances her evidence without resorting to claims about legitimacy—even if her starting point is in fact Vallières.

The blog will be back next week with the final post of 2019, a far less argumentative article on French-Canadian holidays.

Leave a Reply