See Part I here.

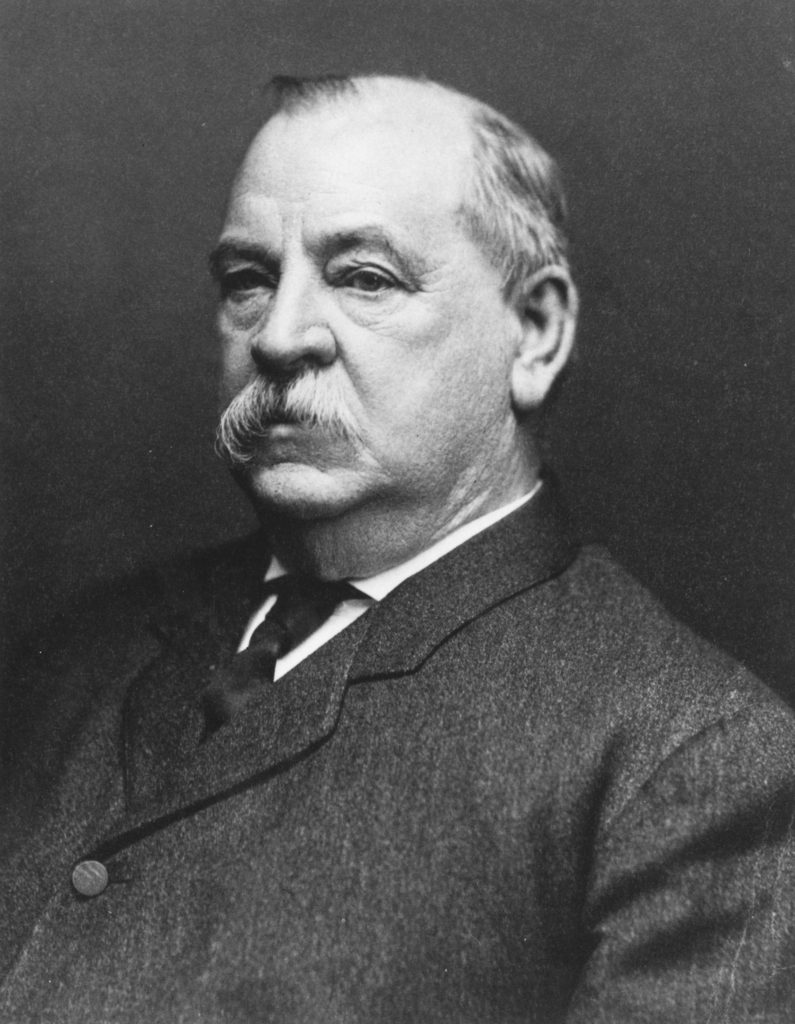

Lenthier was all in for Democratic presidential candidate Grover Cleveland and did likely find party monies to fund his efforts. Even with hindsight, it is unclear how much of this was a matter of ideological principle and how much an opportunity for personal gain.

His papers depicted the Republican Party as enemy of the working class—this was the party of big business and patronage. The tariff issue may have helped him and the Democrats among some Franco-Americans. Further, Edmond Mallet’s dismissal by the Harrison Administration was still fresh in people’s minds.

On the other hand, Republican outlets L’Etoile (Lowell) and L’Echo de l’Ouest (Minneapolis) charged that Lenthier was a Mason (horror!) and had tried to cover it up. As for his papers, he had simply sold his work to the highest bidder. He had first turned to the Republican state organization in New York and, when rebuffed, turned to the Democrats. These papers watched with glee as Lenthier lost a race for a local council seat in Lowell.

They won a small battle. The Democrats won the war. Cleveland scraped by and returned to the White House. That Cleveland won by such a close margin and that Lenthier had been so visible in his exertions for the Democratic campaign helped the first Franco-American media mogul claim some reward from the new president.

In April 1893, Cleveland nominated Lenthier to be U.S. consul in Sherbrooke, Quebec. This may have occurred through their common ally, Josiah Quincy. Quincy was the scion of a distinguished family; as a member of the Massachusetts state legislature, he had conciliated the Irish and proven a friend of organized labor. He too was a partisan animal and, aside from leaving his mark as a mayor of Boston, he was described as “the last of Boston’s Brahmin Democrats.” Geoffrey T. Blodgett explains,

In 1893 Quincy had a chance to prove his partisan regularity in the cockpit of Washington patronage politics, and in the process severed all remaining ties with his Mugwump past.[1] As Cleveland’s assistant secretary of state charged with distributing consular posts during the fight to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, Quincy obediently calculated the votes in every job he dispensed. His performance ignited the hottest spoils controversy of the decade. “He hunts through the departments for patronage places as a pig hunts truffles,” snorted Quincy’s Harvard classmate Theodore Roosevelt. Proper Boston Mugwumps were shocked.

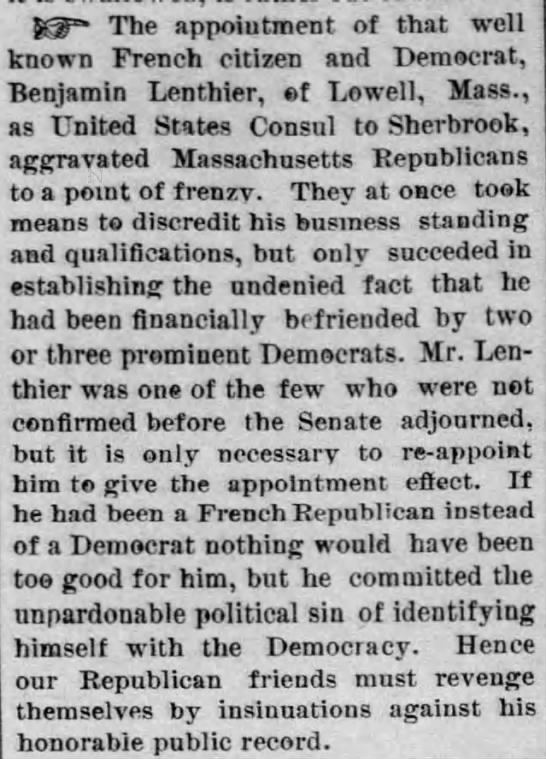

Franco-American Republicans were equally unimpressed when they learned of Lenthier’s nomination. According to L’Echo de l’Ouest, the Democratic Party had already amply compensated Lenthier through its campaign subsidies. There were, what’s more, plenty of other qualified Francos for civil service appointments.

The Senate failed to ratify the nomination before it recessed, but Cleveland simply renominated him and moved forward with the appointment while the Senate was not in session. A Vermont newspaper made it plain that Republicans had been deliberate in withholding their ascent:

Lenthier took up his position in Sherbrooke in early August 1893, amid news of a tremendous economic collapse in the Great Republic.

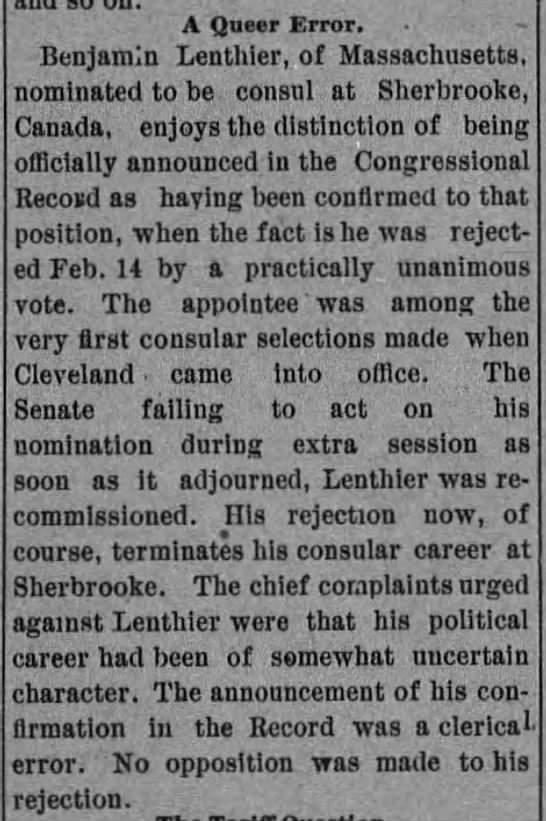

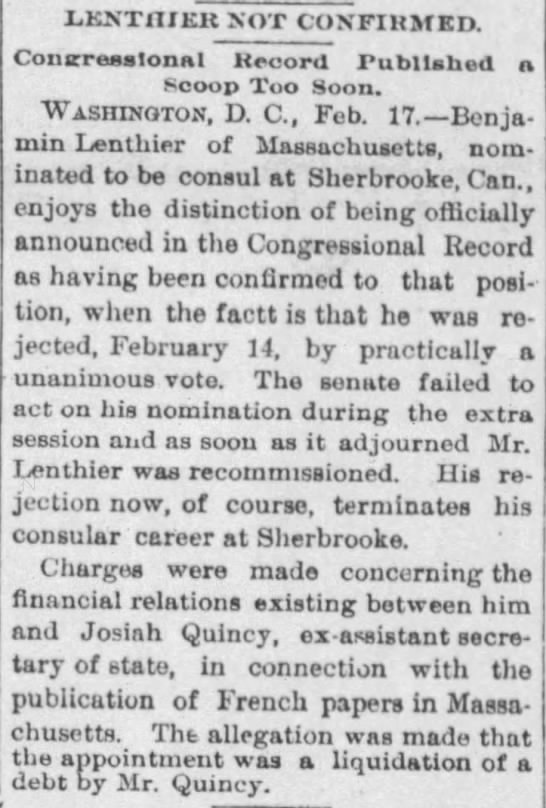

His consulship appears to have been uneventful. It was certainly short. In February 1894, his appointment was again before the Senate for ratification. The message was even louder and clearer this time:

Lenthier had sold Le National to “foreign” interests the previous fall. Now, with the deepening economic crisis, a number of newspapers that had lived past the presidential campaign collapsed and closed. In less than a year, Lenthier had lost both a promising career and a business empire.[2]

Cleveland was ultimately associated with (and held responsible for) the economic depression of the 1890s. Part of the northern electorate was further alienated by Bryan’s populism in 1896. As a result, at the end of the century, the Democrats lost ground to the GOP among Franco-Americans.

As for the ex-consul, Benjamin Lenthier fell on his feet—or rather on a lower rung of party patronage. In 1895, he was earning $1000 a year in Boston as a clerk for the Department of the Interior’s Pension Office. Though he could be found occasionally speaking on political matters—in favor of economic reciprocity with Canada, for instance—in the first decade of the twentieth century, Lenthier receded to a place of lesser importance in the organized life of Franco-Americans.[3]

He died in Boston on February 15, 1922; his wife Julie followed two years later.

Sources

Through civil records, Ancestry.com contains the expected outline of Lenthier’s life but also his patent applications. Contemporary newspaper articles are drawn from Newspapers.com, the Library of Congress’s “Chronicling America,” and the heritage collection of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

See, on Lenthier’s brief media empire, J.-André Sénécal, “Les élections présidentielles de 1892: L’entrée en jeu des Canadiens du Massachusetts ou les limites du vote ethnique,” in Les parcours de l’histoire: Hommage à Yves Roby, edited by Yves Frenette, Martin Pâquet, and Jean Lamarre (2002); on Quincy, Geoffrey T. Blodgett, “Josiah Quincy, Brahmin Democrat,” New England Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 4 (December 1965), 435-453.

Alexandre Belisle devotes an entire chapter to Lenthier in his Histoire de la presse franco-américaine, published in Worcester in 1911.

[1] The Mugwumps were conservative middle-class voters alienated from the GOP, concerned about corruption, and open to moderate political reforms. Political observers have often depicted them as self-important, ambitious, and hypocritical, not to mention their numerous ethnic and class-based blind spots.

[2] Other prominent Franco-American consuls followed, most of them under the Republican administrations of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt: Alphonse Gaulin, Eugene Belisle, and Urbain Ledoux in France (and in Ledoux’s case, also Trois-Rivières); F. X. Belleau in Trois-Rivières as well; Misaël Authier, Lenthier’s great Republican rival, in Saint-Hyacinthe and later Guadeloupe; and one Pierre-Paul Demers in Costa Rica. Sutton’s Alphonse Daudelin also represented the U.S. less formally in France.

[3] That he was creative and far from resigned to the mundane may be seen in patent applications for a new kind of fly trap in 1906 and 1907.

Leave a Reply