Please see Part I here.

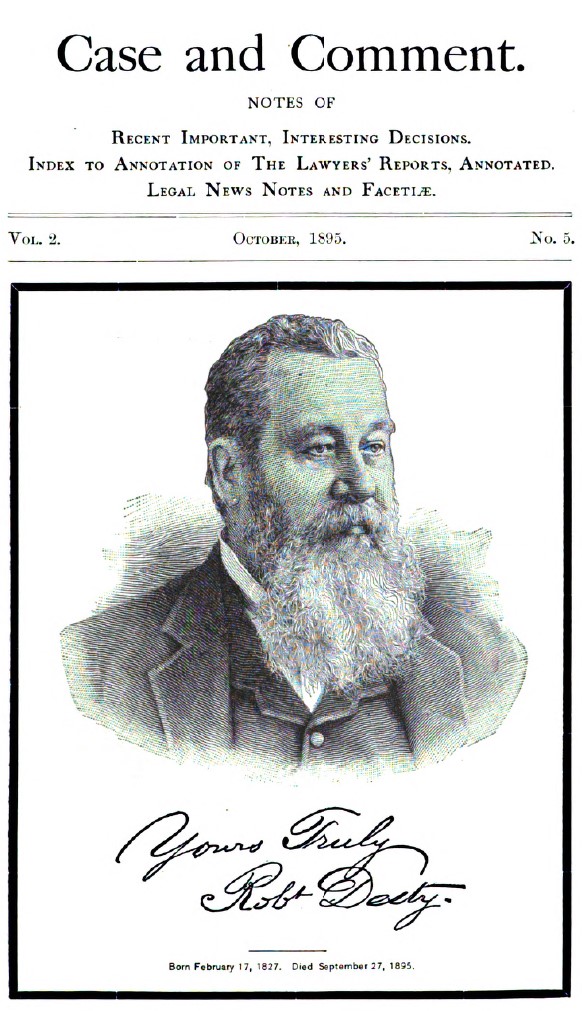

By the mid-1870s, Robert Desty’s life was apparently more settled. He began the work that considerably eased the burden of generations of American attorneys and scholars, and through which his became a household name in the legal community. He compiled and indexed laws and court cases; he wrote digests; he researched antecedents and annotated cases arising in California, the Midwest, and New York. His Manual of Practice in the Courts of the United States was reissued seven times in little more than two decades. (A partial list appears here.)

Desty’s brief foray into elective politics led to more fleeting name recognition. In the 1860s, he had campaigned in support of Republican A. A. Sargent, then a candidate for the U.S. Congress. A San Francisco paper reported that 200 members of the French Republican Club had suddenly appeared during Sargent’s speech at a campaign rally. “When the excitement subsided the band played the ‘Marsellaise [sic] Hymn,’ after which Mr. Sargent resumed his speech. After he had concluded W. H. Sears made a few remarks, and was followed by Robert Desty, a member of the French Republican Club.”

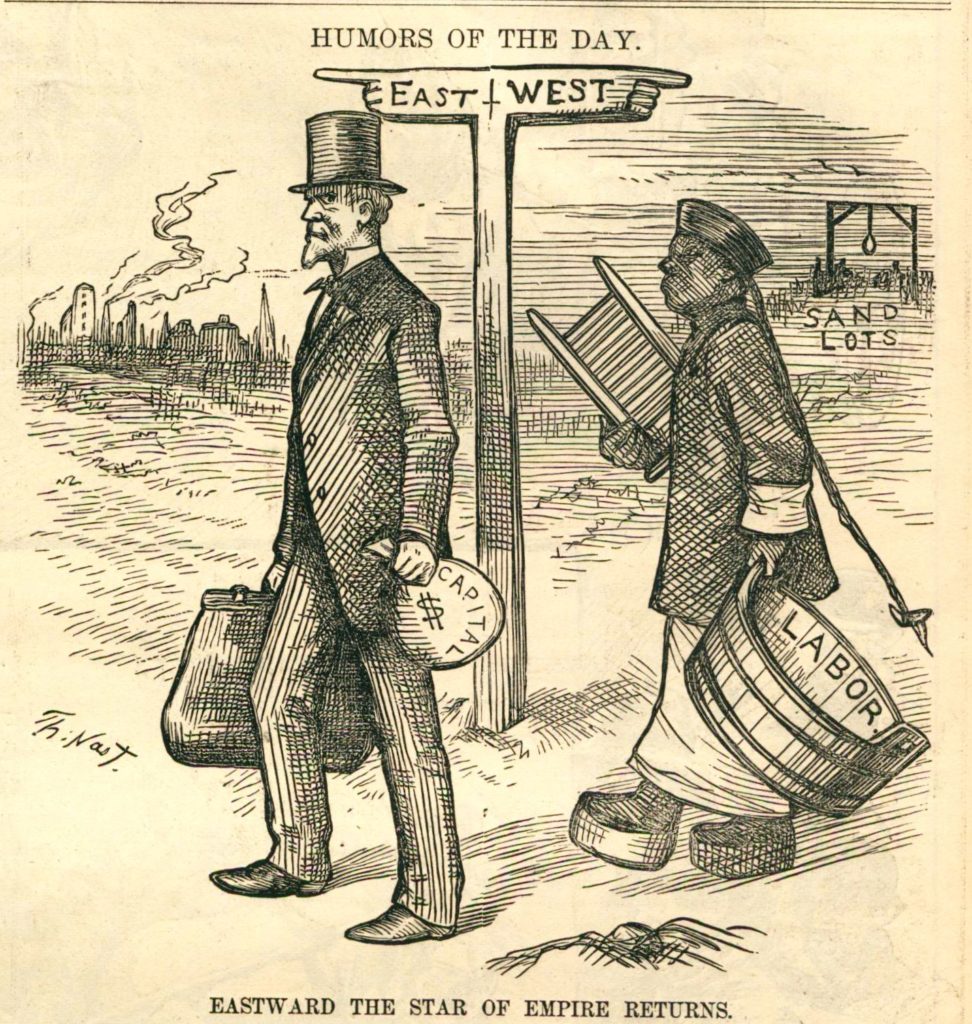

A decade later, it was Desty’s turn to seek office. He was nominated by the “Workingmen’s County Convention of San Francisco” in a bid for a State Senate seat. As a lawyer, jurist, and school principal in the Santa Cruz area, he could claim something of a civic presence; he might also have learned a trick or two from his alleged time as an actor (as per the 1853 letters). In any event, he won—at least in the final vote count. Whether he would actually fill the seat was another matter. It seemed well-known that he was a native of the British colonies and there was enough concern, or hostility to his candidacy, that his opponent, James Byrnes, sought to have the election invalidated on the basis of Desty’s dubious citizenship status.

Some outlets opposed him for entirely different reasons. In September 1879, one editor stated, “if our memory is not defective Mr. Desty did not leave Santa Cruz under the most favourable auspices. Did not pay all his bills, possibly. Our recollection is that he is a man of more brains than character.” But it was the naturalization question that could imperil his political career in the short term. (Ironically, the Workingman’s Party that he represented was particularly committed to the expulsion and exclusion of Chinese from the United States.)

By the end of October, the county clerk had authorized justices of the peace to collect depositions, which he would then communicate to the Secretary of State of California for a decision.

Desty claimed that he had taken out citizenship papers in New York City in 1849; there was, in fact, a record of his application. But evidence of actual naturalization had apparently gone up in smoke in one of San Francisco’s numerous and devastating fires. In the winter of 1879-1880, Desty sought to confirm his status through New York state offices, but in vain. The paper trail suggested that he had declared his intent to become a citizen in 1849, but never formally obtained citizenship status despite living on U.S. soil as early as 1837. He lost his bid to be seated in California’s legislature. Worse yet, as a result of the revelations, his name was stricken from the state’s voter rolls. (He was not the only French Canadian to lose his office after such revelations.)

In 1881, in a 21-to-15 vote, the State Senate resolved to “pay Byrnes of San Mateo $920 for expenses incurred in his contest with Robert Desty.”

The political and legal battle left him resentful. One obituary would note, “The injustice and wrong, as he felt it, of his rejection by the [S]tate [S]enate rankled in his memory, and made him especially bitter toward the politicians of both the leading political parties of the nation, and to some extent, at least, embittered the last years of his life.”

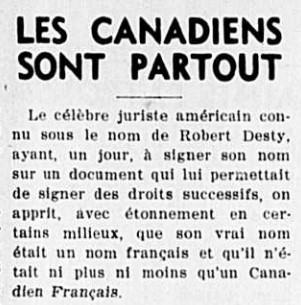

The story became a cause célèbre in California. It was also noticed in Quebec. For Trois-Rivières’ Constitutionnel, there was a powerful lesson in this cruel twist of fate. Under “Ne changez pas votre nom,” the newspaper explained that the unfortunate candidate had actually naturalized under his aristocratic name, Robert d’Ailleboust d’Estimauville de Beaumouchel, in 1849. Soon after, he had adopted his current moniker. There might be evidence that d’Estimauville had naturalized… but was there a citizen by the name of Desty? Le Constitutionnel seemed to invite French Canadians, or at least French speakers, to hold fast to their language and traditions.

Committed though he was to a white American Republic, Desty’s former involvement in the French Republicans of San Francisco shows at least some reluctance to blend seamlessly into mainstream culture. In any event, then as now, California was a truly multicultural endeavor. Los Angeles had a distinctive French presence and was even home to three or four French-language newspapers over time.

Desty formally claimed his citizenship in 1880, but did not stay in San Francisco much longer. If most people seek warmer climes as they age, Desty was again a man of his own mind. Around 1882, he moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he contributed to the Federal Reporter; by 1887, he was in Rochester, New York, where, minus a short time in New Jersey, he spent the remainder of his life. He co-edited the Western Reporter, a legal publication covering jurisprudence from a number of states, alongside Judge Charles A. Ray. Desty was then depicted as “one of the best-known legal writers of the United States.” The electoral saga of 1879-1880 might have encouraged him to leave the Golden State, but evidently it had not hurt his legal reputation.

Desty was associated with the Lawyers’ Co-operative Publishing Company, which issued the Reporter. But whether there was any money in it is questionable, just as it is unclear whether Desty took clients and practiced law. In 1895, the year of his death, the City of Rochester published a list of lots to be claimed and sold for unpaid taxes. Four of those appeared under his name.

Our seasoned jurist died in September 1895, after an “acute illness,” which prevented him from seeing his “magnum opus” (a work on contract law) through to publication.

Notice of his death was carried across the United States. The prominent Franco-American attorney Hugo A. Dubuque, no doubt familiar with his legal writing, paid tribute to him in l’Indépendant (Fall River) and again in the Bulletin des Recherches historiques (Lévis). The Santa Cruz Sentinel, which had cast aspersion on his character a decade and a half earlier, declared, “We remember him as a small, active, energetic, ambitious man, full of brains and ready for any emergency.”

That Desty had an eventful life is an understatement. He was involved in numerous and wide-ranging ventures, many unsuccessful, that might attest to his independent spirit as well as a quest for financial stability. Extremely intelligent, he was clearly capable of hard work, as his legal texts indicate. Yet, it is quite telling that in the euphemistic Victorian culture of the times we do find reports of dishonest behavior.

His wife Mary seems to have followed him to Minnesota, but perhaps no further. She was in Stockton, California when Robert died, and in California she remained until her own passing, in 1906. Robert’s adoptive son, possibly her own biological son, also called Robert Desty, likely stayed with his mother. There is ample room to speculate and it may be simply be that some people are hard to live with. It would not be so surprising that from the scars of war, the rough-and-tumble world of early California, and electoral defeat, monsieur d’Estimauville may have become one of them.

Although the report may be apocryphal, a later biographer stated that Desty had no close family in Rochester and his firm was charged with organizing his funeral—a funeral led no less by an Episcopal Church minister. (If Alemany had only known!) From California his widow sought but failed to have his body returned to her. She also tried to have herself and Robert Jr. recognized as the rightful heirs.

While alluding to the State Senate contest, the San Francisco Examiner declared on Desty’s death that he “was an American through and through.” Indeed: he had fought for his adoptive country, crossed the continent, experienced the gold rush, contributed to the moral causes of the day (as well as to ugly racial nativism), taught the country’s children, taken part in its politics, and added significantly to its intellectual capital—from New York to the Southwestern frontier, from California to Minnesota and back to New York.

Amid the many trials and tribulations of his life, Desty could at least claim to have lived the American promise and to have died an American citizen. How far the ripples of his life may have carried we do not know, but it continues to raise broadly relevant questions—What does it mean to be an American (culturally and legally)? What do we owe to the unnaturalized immigrants of the Great Republican Experiment? As for researchers, I trust it invites attention to the incredibly diverse, multifaceted, and geographical expansive nature of Canadian emigration to the United States.

Leave a Reply