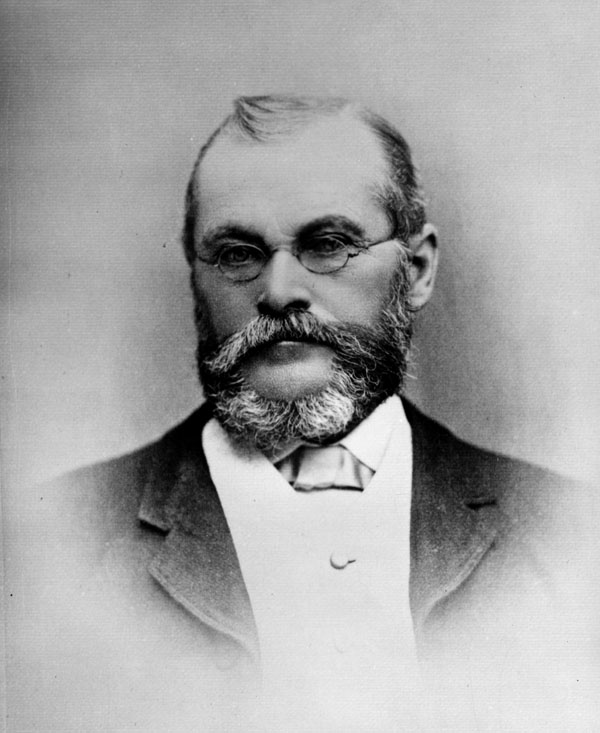

Nobleman. Common Soldier. Legal scholar. Disqualified candidate. French. American.

The contradictions of Robert Desty’s life cannot but make for interesting reading. That he is not better known—another victim of history—is remarkable.

For one thing, to know him by his American name, under which he earned passing fame, misses much of his identity. Desty was christened Robert d’Estimauville in Lower Canada in the 1820s. The record of his baptism, entered at the Anglican Cathedral in Quebec City, hints at his complicated story:

Robert Daillebout, son of John D’Estimauville De Baumauchall Esqre Captain on the half pay of the Canadian Voltiguers & Teller in the Quebec Bank, and of Sophia his wife, formerly Sophia Hunter was born on the sixteenth of February, and baptized on the twentieth March in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred & twenty seven…

The d’Estimauville de Beaumouchel family’s connections to the Americas dated to the final days of New France. Robert’s eponymous grandfather was born at Louisbourg in 1754. A distinguished nobleman and officer, he resettled in England during the French Revolution. He sailed to Quebec City in 1812, where his brother had served the British colonial administration as early as 1776. A similar string of offices followed for Robert (again, our main character’s grandfather). Now a Protestant, armed with an apparent fluency in both of the colony’s major languages, he played a part in most spheres of Quebec’s public life. In his writing, this d’Estimauville lamented the political struggles of Lower Canada (between Patriotes and Constitutionalists) and seemed to suggest that there were indeed “two nations warring within the bosom of a single state,” as Lord Durham would declare.

To Robert d’Estimauville were born several children, including John, mentioned in the church record above. Beyond service in the War of 1812, John left little to posterity, partly because he died at the age of 33. His sole surviving son, Robert, was only three years old then. What followed is unclear, but later evidence indicates that his widow relocated to New York City around 1837. There the oldest child, Sophie, married a Philadelphia man in 1842. (Father Mignault of Chambly officiated when, as a widow, Sophie married a magistrate’s son in Montreal in the early 1850s.)

It was in New York that young Robert, John’s son, entered law school. Following in his forebears’ military footsteps, he enrolled in the U.S. Army and became one of hundreds of Canadian-born men to fight in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). His enlistment record indicates that he was still a student when he joined in March 1847. But it is quite likely that he experienced some of the most dramatic actions of the war, which culminated in the capture of Mexico City in September 1847. A pension indicates that a Robert d’Estimauville was discharged that December. He survived rampant epidemics and poor sanitary conditions and walked away from the field of battle, and the U.S. Army, armed likely with a life’s worth of experiences. Beyond actual warfare, he had met men of all conceivable backgrounds—this was predominantly an immigrant army—and seen the other side of the continent at a time when few Americans, or Canadians for that matter, had.

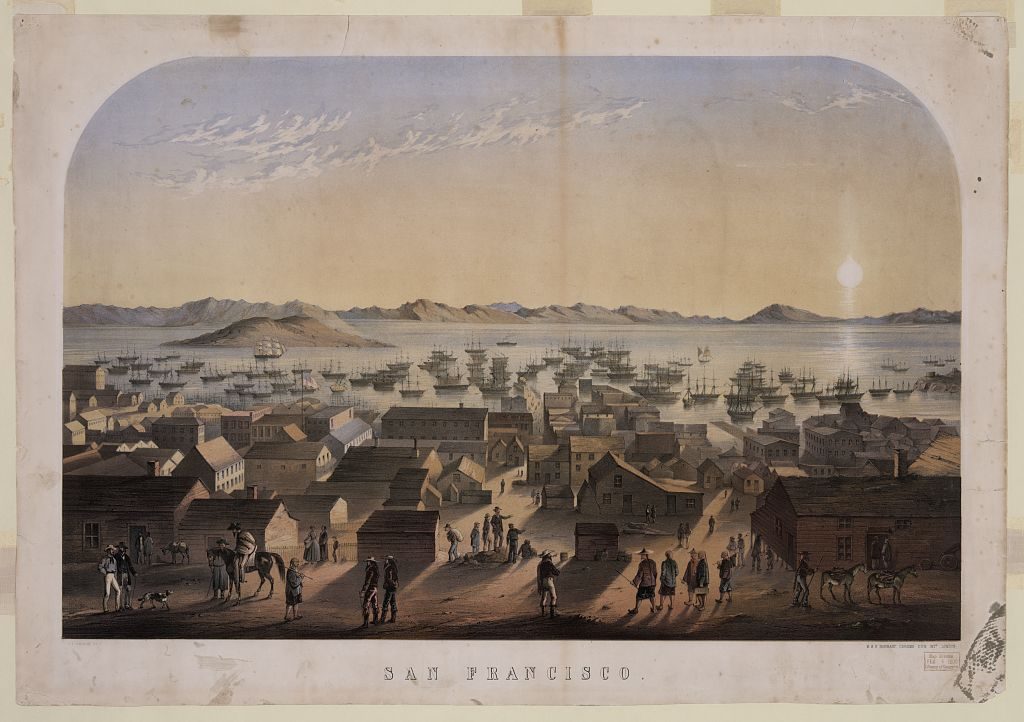

The U.S. Southwest, obtained by treaty from Mexico, apparently suited Desty. At the end of the decade, at the height of the gold rush, he travelled to California. The next we hear of him, aged only 26, is in 1853, from a Quebec newspaper. A letter received from California painted a mixed portrait of the Canadians who had gone west with the Forty-Niners. Out in California were a certain Létourneau, originally from Saint-Marc; Coursolles, from Saint-André d’Argenteuil; Larue, from Trois-Rivières; Racette, from L’Assomption; Turcotte, from Trois-Pistoles; and many more. Some had left Lower Canada at the dawn of the 1840s, others more recently to seek a quick fortune. All attested to growing continental integration even before railways traversed the great North American land mass—this was still, in fact, the heyday of the Oregon and California trails. By no means was Lower Canada isolated from such larger forces. (A native of Saint-Antoine, Damien Marchesseault when to California around 1850, too, after a stint as a riverboat gambler. He eventually became mayor of Los Angeles. A fellow Canadian, Prudent Beaudry, later held the same office.)

Among those mentioned in the letter was Robert d’Estimauville who, after facing reversals in mining, had “returned to the palace of Themis,” meaning the practice of the law. He was apparently still in difficult circumstances. A forceful response arrived four months later. Desty and others mentioned in the original correspondence rejected the author’s claims. Desty was not in Sacramento, as claimed, but in San Francisco, where he was editing a weekly newspaper. What troubles he had faced owed to three successive fires that had consumed his means. He now owned a ranch, supported moral causes like the temperance crusade, and expected to be joined by his family shortly. (It seems more probable that he was referring to a wife than his mother and sister.)

A number of Canadian newspapers printed the reply, when it arrived in June 1853. The Journal de Québec, which had published the first letter about emigrants’ mixed circumstances, defended itself in a few words and pointed to its efforts to deter emigration. This was in keeping with the times. The prior five years had witnessed the first major campaign to halt expatriation in Lower Canada, though evidently there was greater concern about French Canadians settling in the Midwest and New England than venturing all the way to California.

Desty’s varied endeavors over time do seem to point, ultimately, to challenging circumstances, but also to a restless and indefatigable spirit. In bustling San Francisco, in May 1853, he sought to launch a weekly paper, The Catholic Standard, with the approval of Joseph Alemany, the first bishop of California following its U.S. takeover. The federal census of 1860 listed him as an attorney in Weaverville, a small prospecting center near Redding in the northern part of the state. With him then were an Irish-born wife, Mary, of whom we know little, and a boy of 15 born in Texas. Within several years Desty was a school principal in nearby Shasta.

One Charles Murdock would later recall his time in Arcata, in northern California, and the sudden appearance of Desty in the mid-1850s:

There was no school in the town when we came. It troubled my mother that my brother and sister must be without lessons. Several other small children were deprived of opportunity. In the emergency we cleaned out a room in the store, formerly occupied by a county officer, and I organized a very primary school. I was almost fifteen, but the children were good and manageable. I did not have very many, and fortunately I was not called upon to teach very long. There came to town a clever man, Robert Desty. He wanted to teach. There was no school building, but he built one all by his own hands. He suggested that I give up my school and become a pupil of his. I was very glad to do it. He was a good and ingenious teacher. I enjoyed his lessons about six months, and then felt I must help my father.

(By helping at the local post office, Murdock was intrigued to find that Desty was actually a monsieur d’Estimauville.)

Little else is known of Desty through the following decade; surviving reports from subsequent years ultimately raise more questions than they answer. In 1865, the Santa Cruz Sentinel printed a stunning claim which, if false, at least might have hinted at Desty’s reputation. A notice read, “The Temperance Society of Santa Cruz sends greetings to R. D—, Esq., Attorney at Law, ex member of the Dramatic profession, Professor of Elocution, etc. etc., and requests the return of about $80, gold and silver coin, which very modestly stuck to his pockets.” A Weaverville paper added, “If our memory is not treacherous we copied an item from the Sentinel some months since to the effect that Robert Desty was an officer of Santa Cruz Division, Sons of Temperance.”

By 1867, perhaps on account of such reports, Desty was in San Francisco. He edited the New Age, the Odd Fellows’ paper, before launching a literary magazine with Mrs. Washington Wright. “It is got up in very neat style, and the contents of the initial number are generally attractive,” a newspaper shared. This magazine may or may not have been The Pacific Pioneer and Youth’s Literary Companion, which also launched in 1867 with Desty as editor. This latter publication may have appeared for less than two months.

From this point on, Desty now in his forties, his life seems to have taken a more settled turn. He declared his profession as attorney in 1870 and 1880, indicating perhaps that his ventures in printing were labors of love rather than desperate attempts to earn money. He remained in San Francisco, devoted himself to lengthy legal treatises, and began to take part in the political culture of his adoptive city. From these activities he would gain far greater fame and have his name etched in the occasional history book—although most often as a curiosity worthy of little more than a footnote.

Desty’s story will conclude next week on Query the Past.

Leave a Reply