This post is inspired by conversations with historian Jason Newton, who recently published an op-ed on New York State French Canadians in Albany’s Times Union.

* * *

Demars. Facteau. Boyer. Vachereau. Bushey.

From local street names, an attentive visitor would quickly recognize a historic French-Canadian presence in Tupper Lake, New York. As in countless places across the Northeast, grave markers and one or two historical panels reveal the same.

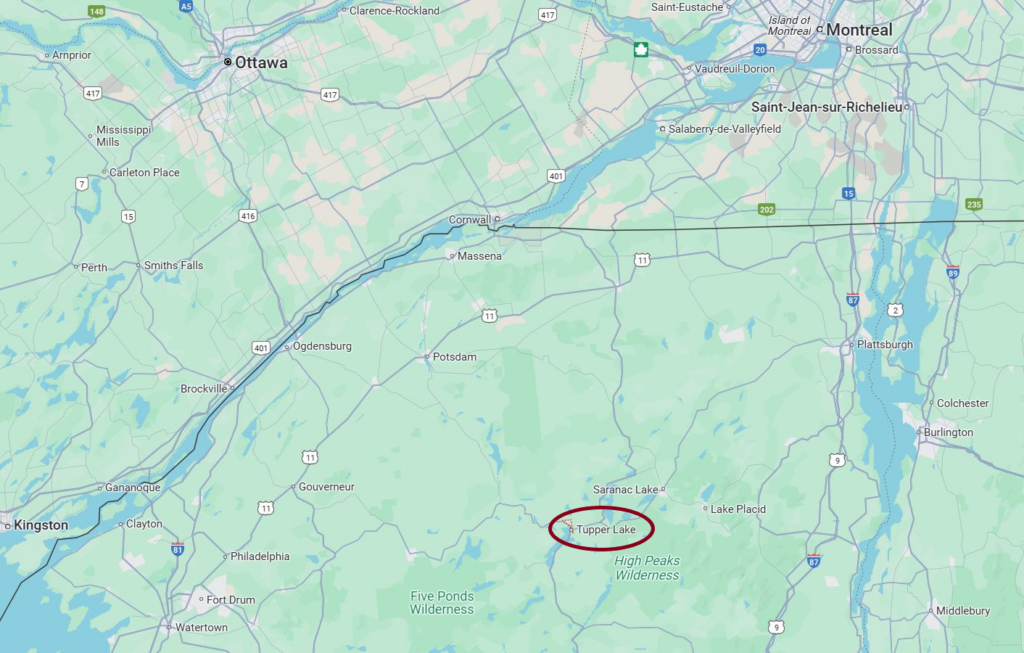

In light of Tupper Lake’s 5,000 or so residents, the name would no doubt send readers in search of a map—or of a distant memory of its mention. The town is located in the heart of the Adirondack Park in upstate New York. Though it may not have the size or name recognition of Fall River, Lowell, or Manchester, French-Canadian immigrants and their descendants played just as important a part in the making of the town, its cultural landscape, and its economy as in those larger locales.

As may be suspected, there are a lot of trees in and around Tupper Lake—and the forest not-quite-primeval served as the town’s economic engine beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century. Though some settlers and loggers had previously ventured into the area, an influx of capital only came in the 1880s and 1890s with lumber baron John Hurd. Hurd was not content to rely on waterways like the Raquette River to float locally-sourced logs downstream to distant sawmills. His efforts and those of well-placed investors brought the railway to the region in 1890. The Adirondack and St. Lawrence Railroad would supplement the Northern Adirondack Railroad later in the 1890s. These connections enabled Hurd and other operators to ship lumber from Tupper Lake mills to markets and, crucially, attract laborers. Local news published in the summer of 1891 tell a tale of rapid development:

Joseph Vandell is building a three-story block for furniture business on the lot formerly owned by R. Donovan . . . John Hurd’s new saw mill is running full blast now and doing good business. The Catholic Church is going up rapidly . . . The Adirondack and St Lawrence R. R. Company paid their help last Monday, and several of the boys were feeling happy that evening and the next day.

Undeniably among that “help” were French-Canadian workers. Just as in Lowell, where Canadians helped build the giant brick structures where their relatives would later work, in Tupper Lake they helped construct railroads that would carry hundreds of their compatriots. In 1889, one newspaper reported, there were some 250 men engaged in extending the Northern Adirondack tracks to Tupper Lake. Largely they were immigrants:

They are divided in squads and the work is pushed systematically. The two great divisions of the men are made according to their nationalities. There are 126 Italians and 110 Frenchmen. The French are divided into one gang of 40 choppers called “right of way men” who clear away the timber from the right of way, another division of 40 do the grading and are called the “bed men” and another division of about forty, lay the rails and are called “trackmen.” The Italians are used exclusively as diggers. The road is entirely in Franklin County.

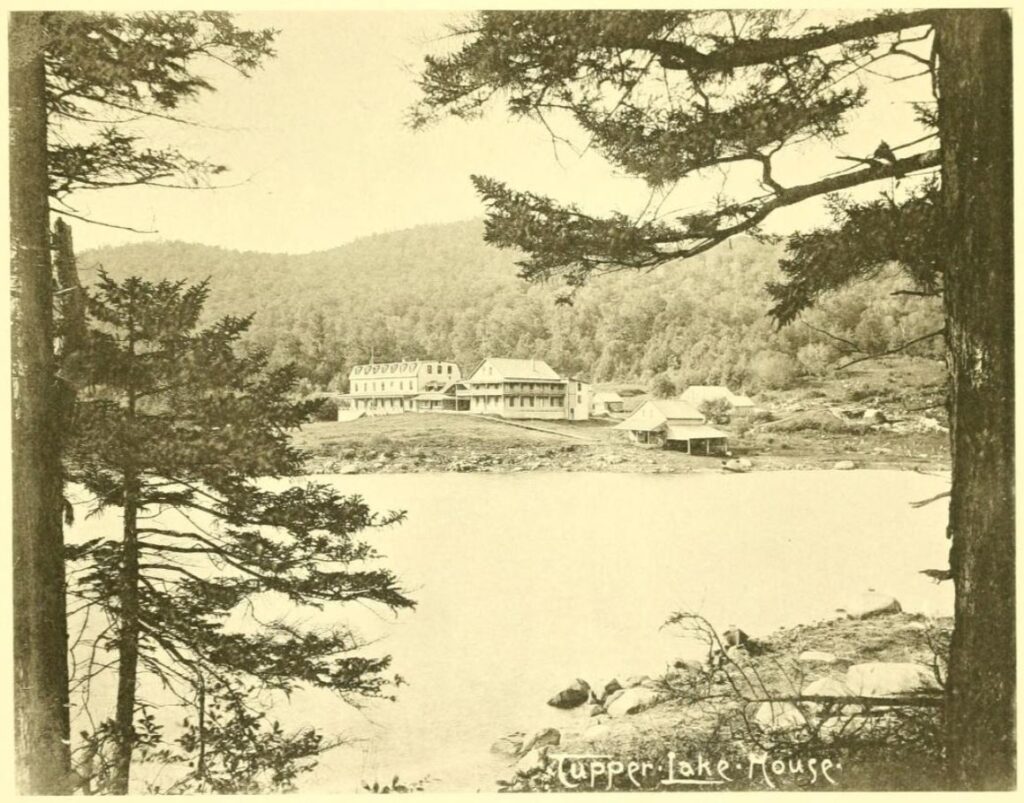

While the capitalist forces spurred rapid development, the Adirondacks were being sold to the very wealthy as a place of relaxation and leisure. Wilderness lodges, and the opportunity to hunt and fish, would enable them to escape the tumult of modern life. Tupper Lake itself was no such place. In 1893, a work on the Adirondacks stated that “[t]he town is a revelation of sudden growth, reminding one of those marvelous western towns that seem to spring up almost in a night; interesting to visit but not a place where the Adirondack visitor would ordinarily care to remain for long.” This was a rough, bustling working-class town that still had a large boarding house population in 1900.

Institutions slowly gave structure and order to social life—outside of grog shops. The Catholic church alluded to above was St. Alphonsus. In 1904, the cornerstone of a new church was laid at Tupper Lake Junction. The Belgian-born bishop of Ogdensburg, Henry Gabriels, attended the ceremony. This largely coincided with Father Anthime Constantineau’s efforts to bring women religious to take charge of the education of Catholic children. It may be due to Constantineau, also, that a société Saint-Jean-Baptiste came into being around the turn of the century.

Mirroring the acculturation process in other locations, Tupper Lake’s immigrant groups were slow to merge with one another. The division of labor that Canadians experienced on the railroad also appeared in the form of geographical segregation and occasional high-profile clashes—not with Italian but Irish workers. In 1905, a cheerful and successful Independence Day celebration in which Canadians participated quickly degenerated. With some hyperbole, a writer reported,

The affair took place in Park Street and was started by some parties who had imbibed too freely of the “genuine red squirrel whiskey” for which Tupper Lake has been noted. A general riot resulted, the parties taking sides with the three or four main participants, French and Irish supporters respectively. One of the Irish contingent, who is said not to have been actively engaged in the melee, was considerably battered up, necessitating the services of a physician, while several on both sides were more or less used up by the fray. The local police force appeared entirely inadequate for the needs of the hour, for it was some time before any determined efforts were made to end the row, and then only two of the participants were arrested. Threats are openly made on both sides that the matter is not yet settled, and it is feared here that the affair may culminate in a genuine race war.

We do not know of further clashes.

Systematic sampling of the federal census of 1900 provides a valuable glimpse of Tupper Lake’s French-Canadian population in that era. Like other methods, systematic sampling has its shortfalls, especially in cases of intense geographical concentration. Still, even while Tupper Lake had its French Village, French Canadians were a substantial component of the population across town. At the turn of the century, 92 percent of Canadian immigrants were of French ancestry. Together, French-Canadian immigrants and American-born children with two such parents amounted to approximately 31.5 percent of the town’s 3,045 residents. This figure does not include people with only one French-Canadian parent, or yet people whose grandparents had left the home country. It seems certain that well over one-third of Tupper Lake’s population was identifiably French-Canadian. They were therefore the largest minority group, though other nationalities had found a momentary home in town: Irish and Italians, as noted above, but also natives of England, Russia, and Syria. Figures provided by Jason Newton show that natives of French Canada represented 7.2 percent of the population of Franklin County, where Tupper Lake is located, in 1900. The logging and milling center therefore stood out as a destination for French Canadians.

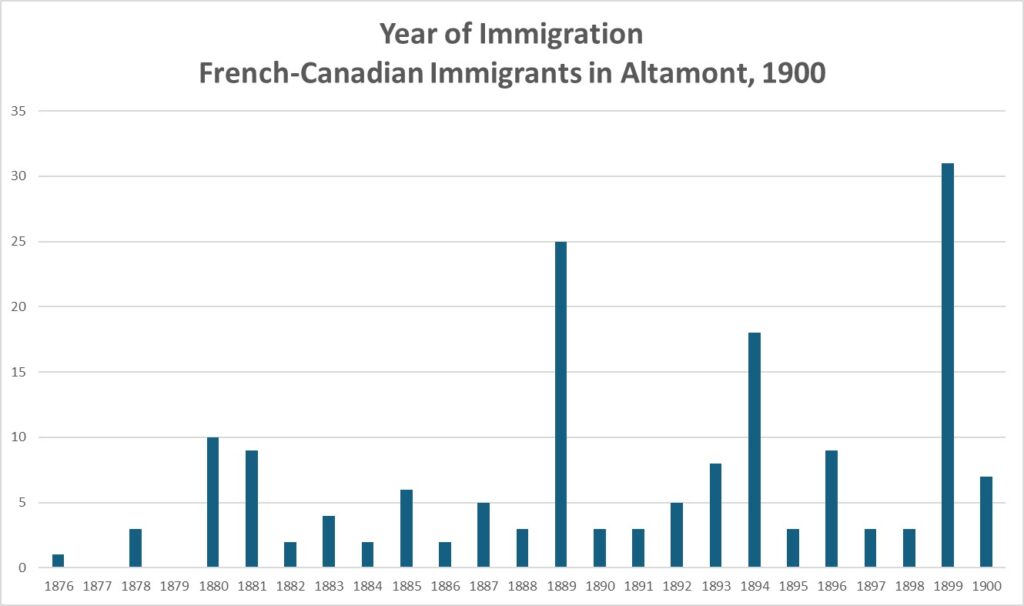

One married couple had immigrated to the United States in 1850. However, within the sample, most natives of French Canada had crossed the border in the twenty-five-year span leading up to the census.

The bars of the early 1880s reflect one of the peaks of immigration from Quebec. The number for 1894 is a surprise, since by then the U.S. had entered a severe economic crisis. The spike in 1889 seems to reflect the arrival of several large families. A large fire swept through the downtown area in 1899. A call for workers may have carried across the border and brought workers in various sectors to help rebuild in its wake. It may well be that this population had disappeared from Tupper Lake by 1910. In any event, few of the residents who had immigrated prior to 1889 are likely to have come first to Tupper Lake. As the town grew, it likely attracted immigrant workers from Plattsburgh, Saranac Lake, Malone, and Ogdensburg.

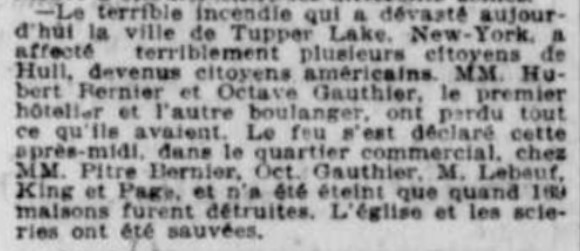

In August 1899, a Montreal newspaper commented on the fire that had destroyed the businesses of many former residents of Hull, Quebec, now living in Tupper Lake. We see hints of this migratory relationship between the Ottawa valley and Tupper Lake in several places. This owed in part to infrastructure, including the town’s railway connection to Ogdensburg and beyond. The cross-border tie was cemented in October 1900 when a new bridge over the St. Lawrence River at Cornwall came into use. Additionally, to meet their labor needs, Tupper Lake operators may have advertised positions among the loggers and lumber workers of the Ottawa River and its tributaries. Skilled craftsmen and entrepreneurs would have followed. Hubert Bernier, who left Hull in 1890, was among them. His hotel went up in flames in 1899. Still, folks came from other regions. Georges Vallée and his adult son left Saint-Casimir, west of Quebec City, to work as lumberjacks in Tupper Lake. Sadly, within a month, one of them was dead, the victim of a perilous river crossing.

These lumberjacks were typical of the trades in which immigrants found work. The sample mentioned above included 106 French-Canadian immigrants with listed occupations. Among them, there were 28 different occupations. The most common were day laborer (41), lumber piler (11), and sawmill laborer (11). A majority of the other occupations were connected with lumber: river driver, sawyer, sawmill engineer, etc. There were several skilled craftsmen, including a mason, three carpenters, and as many blacksmiths. Not all were manual laborers. Lewis Bora, now in the United States for thirty-five years, had risen through the ranks to become foreman. Lewis Cote either operated or worked in a grocery store.

Then there was Evariste Leboeuf, a hotelkeeper who had immigrated around 1878. Leboeuf had grown up just across the St. Lawrence from Saint-Casimir. Seemingly indefatigable, he was, in the 1890s, the progenitor of Tupper Lake’s telephone network. He sold his hotel in 1900 to focus on his telephone company, which in turn he left in 1901. A year later, in the first village elections, the Republican Party nominated Leboeuf for the position of village treasurer. Four years later, he became village president. Two French Canadians were elected as trustees at the same time.

Of the 106 individuals with stated occupations in our 1900 sample, two are women, one being a servant. The other kept a boarding house. Her name was Sophie Demars; she was a Potvin by birth. With a large family, Sophie and her husband Joseph or Janvier Demars immigrated from the Ottawa region in 1886 or 1887. After her husband’s 1894 death, with her children aging into the workforce, Sophie chose to take in boarders. She was still taking guests in 1910, when she had six boarders. Five of these were French-Canadian and all of them were engaged in lumber trades. In an interesting twist, daughter Victorine would eventually move to another lumber center with a large French-Canadian population: the town of Cascade, just south of Berlin, New Hampshire. Intense focus on the textile industry has perhaps concealed the intense familial and ethnic ties between logging and lumber-producing centers across the Northeast—through Quebec, Ontario, Maine and New Hampshire, and of course upstate New York.

This far too brief glimpse of Tupper Lake’s ascent underscores the continued need to broaden our historical lens. Recent works like Déploiements canadiens-français et métis en Amérique du Nord (18e-20e siècle) and a recent thematic issue of Recherches sociographiques have pushed the boundaries from a geographical standpoint while integrating New England centers in a larger regional, interregional, and continental story. In the short term, we can afford to bring more of these case studies into the conversation and continue to capture lesser-known stories. This work can only make Franco-American history more comprehensive, more honest, and more engaging.

Sources

The census of 1900 was accessed on Ancestry.com; Ancestry databases helped reconstruct the lives of Evariste Leboeuf and Sophie Demars. The direct quotations are taken from the Adirondack News [St. Regis Falls], July 25, 1891 and July 15, 1905, and the Ogdensburg Advance and St Lawrence Weekly Democrat, August 15, 1889. Overviews of the town’s growth appear in the Courier and Freeman [Potsdam], September 2, 1891, and the Malone Palladium, April 5, 1900. See, on the Vallée family, Le Progrès de l’Est [Sherbrooke], October 7, 1904; on Leboeuf’s activities, the Adirondack News, June 16, 1900; the Norwood News, May 28, 1901; the Malone Farmer, June 11, 1902; and the Utica Observer, March 21, 1906. For those seeking to dig deeper, I will happily provide additional sources on request.

I am indebted to Tupper Lake: Early Beginnings, a Facebook page with terrific photographs and excerpts of historical newspapers. Genealogical researchers may be interested in the Northern New York Tombstone Transcription Project and its data on Tupper Lake and surrounding towns. Jason Newton’s work on the logging industry is accessible in his Labour/Le Travail article and in his recent book, Cutover Capitalism.

Further Reading: Those Other Franco-Americans

- Exeter

- Somersworth

- Berlin (Part I, Part II, and Part III)

- New York State

- Barre

- Cohoes (Part I and Part II)

- St. Albans (Part I and Part II)

- The Madawaska Region

- New Bedford (Part I and Part II)

Leave a Reply