See Part I here.

His arduous journey was still far from over as Bishop Plessis definitively left Halifax on July 27. A carriage provided by a Mr. Conroy took them overland to Windsor, a town with a small estuary opening on the Bay of Fundy. Plessis seemed startled to find a good number of Black freedpeople working as laborers on the road to Windsor; many of them, he believed, had been seized from U.S. ships and dropped off in Halifax out of convenience during the War of 1812.

More than a generation before the publication of Longfellow’s A Tale of Acadie, Plessis knew—perhaps from local tradition—of the tragic events that had taken place near the Mines (Grand-Pré). But, if local history hadn’t been entirely erased, a people had been: Plessis found no Acadians as he traveled from Halifax to Windsor and then down the Annapolis Valley. At last he reached la baie Sainte-Marie, where the French-speaking population was substantial. He heard of Amable Doucet, deceased, a justice of the peace who had advocated for the Acadians and protected their settlement in the region. And Plessis met another illustrious Acadian: the abbé Jean-Mandé Sigogne, who was deemed a holy man by those who met him. Beyond his spiritual work, Sigogne did not shy from physical labor—he dry-fitted his own stone wall—for in many respects he had to support himself. Yet there was no such thing as “trickle-down holiness.” Plessis found communities of “heretics” between Argyle and Pubnico.

From St. Mary’s Bay, Plessis crossed to New Brunswick. Though Catholics might be barred from the highest offices in these colonies, he and his entourage generally enjoyed cordial relations with the Protestants they met. That is not to say that a red carpet was unfurled for them. The bishop complained of abusive prices for lodging and meals after departing Halifax. Perhaps local residents and innkeepers determined that a bishop had deeper pockets than the everyday wayfarer.

Still, some hosts were downright penurious. In Fredericton, the group arrived at a small inn after the evening meal and had to share three eggs—the only food they were given—between them, and this after the bishop had fasted all day. Plessis, hardly one to feel slighted, was insulted when offered rooms in the back of the inn where, he stated, drunks would repair to save themselves public shame.

On small vessels and canoes, Plessis and friends pushed into the interior of New Brunswick to visit Maliseet bands, whose culture and language had become increasingly syncretic as other displaced Indigenous groups (Mi’kmaq, Abenaki) joined them. The influx of Acadians and French Canadians on the Upper St. John River was now causing further displacement. Plessis was not a particularly careful or interested observer of Indigenous customs, but his notes do include valuable information on the history of Catholic missions to the original inhabitants of the northeastern woodlands.

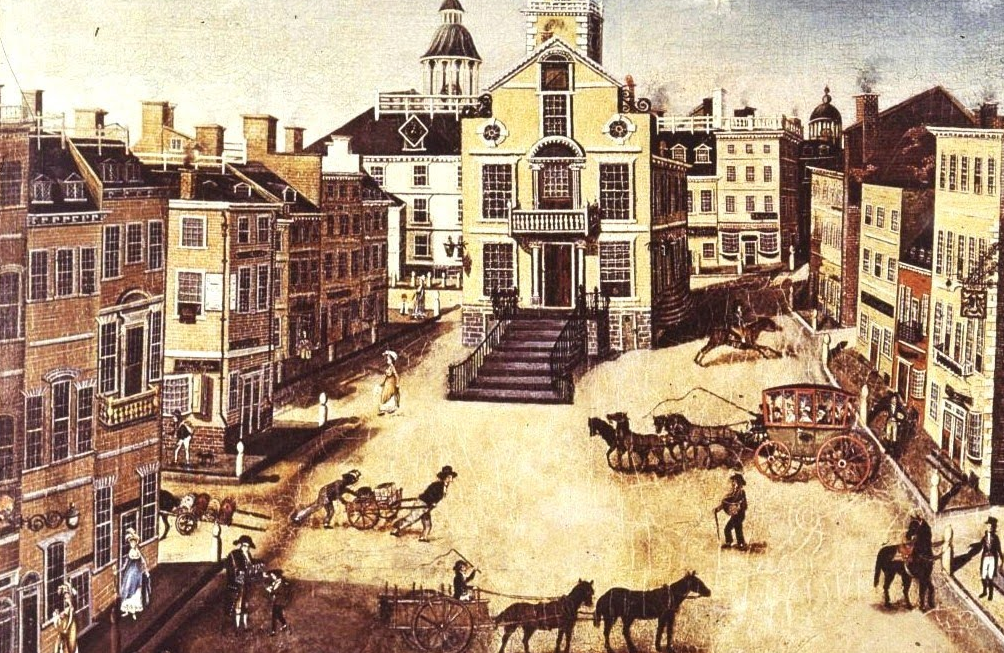

The clergy left New Brunswick on August 31; their ship dropped anchor in Portland, Maine, whose cityscape reminded Plessis of Montreal’s, as one approaches the city from La Prairie. On they quickly proceeded to the impressive metropolis of Boston… with its 36,000 residents.

From Plessis’s journal we seem to find in the United States the same relative religious amity that had begun to develop in the British colonies—not inclusion or ecumenism, but growing tolerance. Plessis celebrated Catholicism’s foothold in Puritan Boston, the freedom of religion promised by the U.S. Constitution, and the disappearance of Pope’s Day rituals. There was hope for even more cordial Catholic–Protestant relations and for a recognition of Catholic rights. Such optimism would be dashed recurrently from the 1830s forward. (Read about the Charlestown convent affair and the Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk for more on this.)

Plessis’s brief time in the United States came before the most violent episodes of nineteenth-century bigotry. It also preceded the consolidation of a distinctly Hibernian episcopacy. He met France-born Jean Cheverus, the unpretentious and welcoming bishop of Boston. Together they attested to a transnational French Church whose tentacles were then far more probing than those of an Irish clerical diaspora. Neither Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore—the founder of the American Church who had visited Canada at the time of the Revolution—nor Cheverus’s successor, Joseph Fenwick, was Irish.

Plessis and his associates debated whether to return to Canada overland through Burlington, Vermont, or through New York City and up the Hudson. The former was the more direct route, but the bad roads from Boston to the border would cause delays and discomfort. Plessis was also curious to see New York City. The group took a carriage from Boston to New Haven (through “Wouster” and Hartford) and then boarded the steamboat Fulton, a glimpse into technology that would revolutionize North American travel and spare Plessis’s successors the same challenges. On the twelve-hour crossing from New Haven to New York, Plessis reflected,

It takes little observation to be convinced that these Americans, from whatever part of the Union they may come, are generally peaceable and reasonably polite, even if they do not have the refined, deliberate, and courteous manners that we find in other nations—manners that we interpret as politeness, but which they are not. It occurred naturally to us, at the sight of the tranquil disposition of these passengers brought together fortuitously, that an equal number of French people or Canadians would have made more noise in an hour than this crowd in twelve.

Plessis also weighed in on the perennial Boston v. New York rivalry:

In the meantime, night had fallen, and it enabled us to freely contemplate the pleasant effect of the illumination that every day takes place in this city. It gives character to the shops whose goods were still laid out when we passed on the most beautiful street in all of America, Broadway, which is surpassed even in Europe only by an avenue built several years ago in Hamburg. At least, such is the idea and vanity of the citizens of New York for their thoroughfare, which is a hundred feet wide and runs straight for over two miles. It is the marvel of New York City, or the most striking one, especially for strangers who did not come to visit but are only passing through. The city as a whole is inferior to Boston in regard to the cleanliness of streets, and its port presents itself less advantageously, though 100,000 residents call this city home. By virtue of its extensive commerce, it is believed that New York is destined to one day be the capital of all English-speaking America.

According to Plessis, of New York City’s population, 15,000 were Catholics, but they were served only by three Jesuits. Evidently the American Catholic Church was in its infancy; the dioceses of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Bardstown were in fact each less than a decade old in 1815.

Another steamboat, departing the metropolis of the future on September 11, brought the clergymen to Albany—in twenty-eight hours. In this pre-canal era, they took carriages overland from Albany to Whitehall, at the southern tip of Lake Champlain. That stretch of the journey reminded the travelers why they had chosen to go through New York City. The roads were muddy and uneven, and the descent into Whitehall was so rough that the men expected the carriage to break apart at any moment. Still, Plessis could appreciate the historic sites he passed through; the significance of Saratoga—again, the battle was within living memory—was not lost on him.

Having missed the steamer to Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River,[1] Plessis and company, eager to be back home, boarded a sloop. On that ship they had to find space between shipping crates, lumber, and other freight destined to various points along the lake. They would also have to wait days for favorable winds to actually send them on their way.

On board they became acquainted with a woman who, though nominally Protestant, didn’t have fixed beliefs. This again gave Plessis hope for the Catholic faith on American soil. So did the presence of a hundred French-Canadian Catholics in Burlington, the beachhead of a diaspora that would occupy Father Mignault a generation later. The company stopped in Plattsburgh and on September 18 they passed the Ile-aux-Noix on the Richelieu.[2] That was less than three weeks after leaving New Brunswick, no mean accomplishment, in this era.

In all, when arriving in Saint-Jean, Plessis had not set fought on Canadian soil—recall that the lower colonies were not Canada at this time—since June 11, exactly one hundred days. He then reflected,

In truth, after treading the sandy streets of Burlington and the beautiful walkways of New York and Boston, it was no delight to go about ankle-deep in mud as we did in Dorchester [Saint-Jean], or to zigzag to avoid mud holes that would have swallowed shoes and maybe boots. But, after an absence of some time, we endure in our homeland the inconveniences against which we would protest were we to encounter them abroad.

* * *

The expression “two solitudes” typically refers to English and French Canadians and the palpable cultural barrier that has historically divided them; these were groups very often with distinct social universes. But there have been multiple francophone solitudes in Canada and the U.S. Northeast, most obviously the French Canadians and Acadians. These groups came together socially in the Madawaska region and later in certain American urban centers. Otherwise they were only connected on occasion at the elite level. Plessis hinted at the prospect of connecting these two worlds. In a way, that could happen religiously, but, as these societies navigated distinct economic and political realities, the fracture would ultimately persist down to the present day.

Plessis’s travel diary also matters as a glimpse into a larger North American world to come. In 1815, this was already a cosmopolitan, ethnically and racially diverse setting in which the biggest barriers were not borders, but bad roads. Exchange had resumed quite naturally following the end of the War of 1812 (in some areas the war had actually failed to interrupt commerce). In the next generation, canals and railways would reorganize the continent’s geography, opening in their wake new opportunities and new challenges. The barriers of culture would subsist.

Plessis’s journal is available on-line through the Collections patrimoniales of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

[1] Some may find striking that the Champlain–Richelieu axis was again well-integrated so soon after the War of 1812. The Battle of Plattsburgh had taken place almost exactly a year prior to Plessis’s journey on Lake Champlain.

[2] Plessis became more comfortable in Plattsburgh when a widow disembarked and vacated her large room on the sloop. That woman, by the name of Chandonnet, may have been the wife of a Revolutionary War veteran who, in life, bearing invisible scars, would use the whip “freely” on their children.

Leave a Reply