It’s a long way from the lowlands of the St. Lawrence to the Valle de México. As someone who once spent eleven hours simply trying to cross Montana, I can vouch for the almost unimaginable size of this continent. So too will anyone who has crossed North America by land. It is all the more incredible, then, that well before railways traversed these great expanses, some 1,500 Canadians signed up in the U.S. Army to fight a war in Mexico. Although troop movement also occurred by sea—as in the famous assault on the port of Veracruz, in 1847—the presence of Canadians in the ranks attests to growing continental integration in the 1840s.

Under President James K. Polk, a dispute over the Oregon boundary had raised tensions between Britain and the United States. But another Anglo-American conflict was not to be. In 1846, border clashes in Texas led to an American declaration of war on Mexico; Britain and the Great Republic quietly resolved their differences soon thereafter. The Mexican-American War was brief—shorter, even, than the War of 1812. Despite considerable domestic opposition to this conflict, seen by some as a war of aggression or a war of conquest, the U.S. Army quickly reached its objectives. Mexico City fell in September 1847. In March and May 1848, respectively, the United States Senate and the Mexican government ratified a peace treaty that transferred a territory of over one-million square kilometres to the victor.

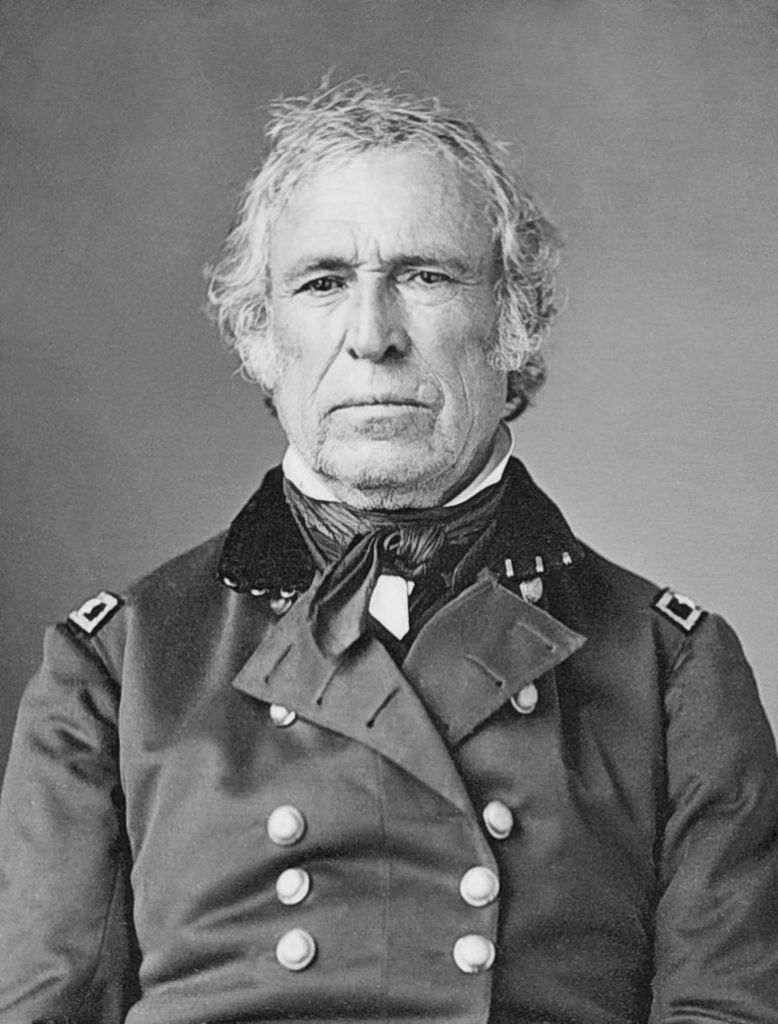

All of this might seem worlds apart from the daily experience of young men in British North America, or recent emigrants to the United States, in the 1840s. Many would in fact only encounter the war in newspapers. On the other hand, recent estimates suggest that nearly half of General Zachary Taylor’s army was foreign-born. Enlistment records show a high proportion of Irish- and German-born soldiers. Many other European countries and territories were represented in the ranks, as was British North America.

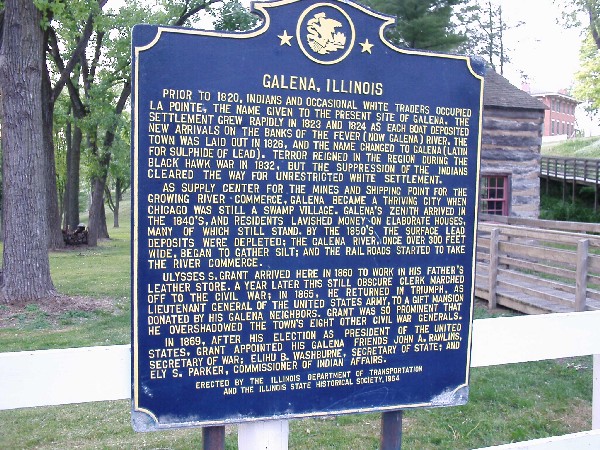

Estimates vary widely, but it is reasonable to think that some 50,000 men from the Canadas and the Atlantic colonies joined the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Enlistments during the Mexican War—at a time when railways had yet to cross the border—were far below that number. At no point did Canadians sign up en masse either for adventure or for steady pay in the U.S. Army. Sign up some nevertheless did. Those who did were probably already living on American soil, or had some connection to the United States. Approximately 40 percent of the Canadian-born soldiers enlisted in places well away from the border, from Bangor, Maine, to points along the Erie Canal, to Galena, Illinois—and further south, as far as Missouri and Louisiana.

As previous noted (here and here), the mass migration from French Canada had already begun; in the short term, there was also ample reason to be pessimistic about the colonies’ future. Insofar as we can differentiate them, ‘push’ forces were likely as powerful as the ‘pull’ of the American army and American economic growth.

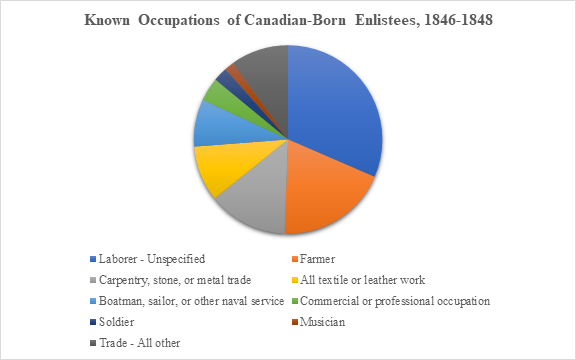

A sample of 500 men born in British North America (enlistment records do not provide the last place of residence) tells us very little about their experience of the war. But places of enlistment do offer important clues as to the growing commercial integration of the continent and the varied industries that drew British subjects to the United States. Many men enrolled in regions of heavy primary resource extraction; others in ports and along major waterways. Undoubtedly, some of those who signed up for military service were farmers’ sons with limited prospects. Yet, approximately half of all enlistees had been born in the major towns and cities of British North America; most were either skilled or unskilled laborers who were not engaged in agriculture. It may very well be, then, that the depressed condition of trades in Canada was one of the leading catalysts of the vast movement that poured three million Canadians onto American soil in the century to follow.

Of course, this should complicate, not entirely erase, conventional explanations about displaced farmers and laborers in rural Lower Canada. The French-Canadian sample in enlistment records may not be representative of larger trends; these migrants were less likely to have the cultural capital to join the U.S. Army and, thus, American institutional life.

But some did—including brothers Francis and Mitchel Cross, whose listed place of birth was “Maska.” For François and Michel Lacroix, it was a long way from Yamaska to Mexico, through Whitehall and possibly New York City. We know all too little about what they saw—whether they experienced discrimination as a result of their faith or ethnicity, or how often they saw battle. We do know that this proved to be a one-way trip for François, whose early demise was likely the result of a cholera outbreak rather than fighting. Michel earned his U.S. specie, gained the cultural capital he needed to thrive in English-speaking settings, and eventually returned to Canada. He died in Sweetsburg, Quebec, in 1901.

At the present stage of research, the impact of the Mexican-American War on emigration from Canada cannot be measured. But enlistment records enable us to reconstruct major points of origin and destinations for Canadian migrants; we can also begin to speculate as to the influence of returning soldiers—who had seen not only “the elephant” but also brickyards, canals, and railways—on the mindset of family and friends back home. In their experience may lie a crucial connection to the chain migration that would continue well into the twentieth century.

Scholars have begun to look into migratory ties between Mexico and Quebec; Carlos Aparicio and Etienne Rivard inquire into the subject in the latest edition of Louder and Waddell’s Franco-Amérique (2017). Readers may also want to look into François-Marie Patorni’s blog on the French of New Mexico.

You can read more about my work on the Canadian diaspora in the era of the Mexican-American War in an upcoming issue of the International Journal of Canadian Studies. Stay tuned for more information.

Pingback: Transnational Tales of the Civil War, Part I - Query the Past