A more extensive version of this post appeared as “The Political World of Franco-Americans” in the summer issue of Le Forum (University of Maine).

After decades of inconsistent research, questions about Franco-Americans’ political involvement abound. Though we should not underestimate the contributions and insights of such scholars as Norman Sepenuk, Madeleine Giguère, Ronald Petrin, J.-André Sénécal, and Christian Potholm, the need for additional research—for greater precision—remains.

What explains, for instance, strong Franco support for the Democrats in northern New England cities, in the early twentieth century, when their compatriots in the southern half of the region consistently preferred the Republicans? To what extent could Franco-Americans expect political power and influence in the GOP-dominated states of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine? At the regional level, did they seek to align the ideology of survivance with their political aspirations? Were they a cohesive voting bloc at the local level, and what issues drove them to the polls—or to a certain political party?

My monograph, “Tout nous serait possible”: Une histoire politique des Franco-Américains, now available from the Presses de l’Université Laval, aims to answer some of those intriguing questions.

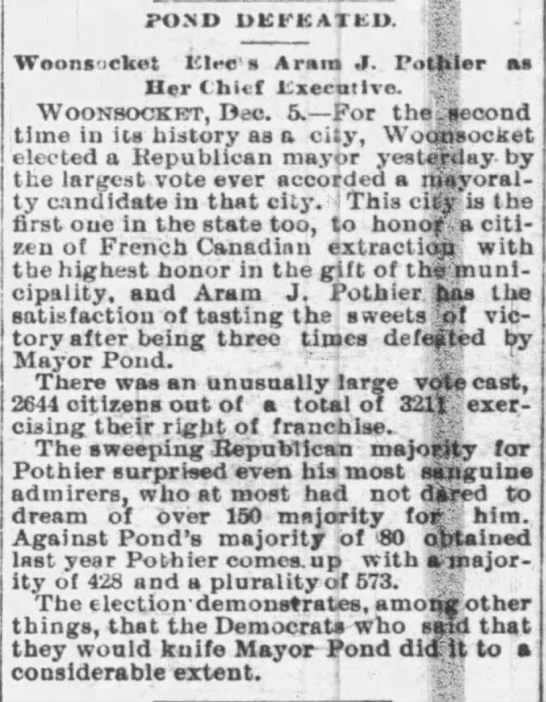

The critical chapter in this political saga takes place in the 1890s. Though their naturalization was gradual and uneven, at century’s end people of French-Canadian descent were asserting themselves in politics and finding ethnic representation across the region. During the presidential campaign of 1892, editor Benjamin Lenthier built a newspaper empire in support of Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland. Cleveland won and rewarded Lenthier with a consular appointment. Another federal civil servant, Edmond Mallet, had become a symbolic figurehead to the Franco-American community. In 1893, Louis J. Martel launched his first bid for the mayoralty of Lewiston, Maine. He lost, but compatriot Aram Pothier, a future governor of Rhode Island, won in Woonsocket. In Worcester, Massachusetts, the Democratic Party nominated two Franco-Americans for common council seats, including a brother of the editor of L’Opinion publique.

Then there was Fall River, Massachusetts. By the 1890s, French Canadians were a well-established and essential part of the spindle city’s labor force. With growth came conflict. The Irish working class—the Democratic Party’s base—resented French Canadians for their reluctance to support strikes. Attorney Hugo Dubuque explained that Canadians refused to take part in the “insurrection” of labor against capital. Instances of strikers pelting Canadians with rocks came to symbolize not only Franco-Irish conflict, but, in the immigrant imagination, the disorder that attended industrial walkouts. The Irish also resisted efforts to establish separate Catholic parishes—which would draw resources away from their own established churches. At the same time, the world of Lent and company tenements could hardly be farther, socially and economically, from the English-speaking citizens likely to support the GOP.

Already, in the 1890s, Fall River Franco-Americans had the reputation of preferring the Republican Party. But, as one local journalist noted, many Franco-Americans were happy to make an exception when Democrat John W. Coughlin—mayor starting in 1891—was running for office. Coughlin, it should be noted, was born to Irish immigrants. He showed that political narratives aren’t immutable.

We can debate the sincerity of Coughlin’s outreach to residents of French descent. That he was reaching out was nevertheless a major step forward. We might think of a musical soirée held in the local Franco community in 1893. The night’s main feature was an address on the Patriotes by L. O. David, the president of Montreal’s Saint-Jean-Baptiste society. Coughlin attended and was invited to offer a few words. He stated how proud he was to be present and expressed admiration for the Patriotes in their struggle against tyranny. During the mayoral campaign, he held events in the halls of the Union canadienne and the Ligue des Patriotes—thus recognizing Franco-Americans’ electoral significance and bringing the world of mainstream U.S. politics to them.

What about those Fall River Franco-American professionals and businessmen who helped give shape to the community? Well, Coughlin had a not-so-secret weapon in the person of Hugo Dubuque, who had served in the state legislature. Dubuque was an avowed Republican; he also happened to be Coughlin’s brother-in-law. They campaigned together. Journalist Rémi Tremblay also lent his support to Coughlin, such that the latter could brag about being accompanied by “[t]he leaders of the French people.” (He also claimed that Dubuque had given more to the GOP than he had received in return, which must have made for a sharp exchange at Thanksgiving.)

The 1893 race between Coughlin and his adversary, former Republican mayor William Greene, revolved around alcohol licenses, the religious issue, and the willingness of each party to appoint Franco-Americans to public offices. At a rally presided by Alfred Plante in Globe Village, Greene offered the same assurances and cordial feelings as Coughlin. He highlighted the French element’s contributions to the city and stated he wished he could address the audience in their own tongue. He claimed he had appointed a number of Franco-Americans to office during his previous time in office. On the other hand, Coughlin’s administration had witnessed an uneven and preferential enforcement of the licensing law. Further, the GOP’s high-tariff policy was cited as being more favorable to mill workers.

Questions about Republican xenophobia dogged Greene through the campaign. Anglo-American nativists were certainly more likely to support the GOP. At the local level, however, Republicans were practical. This was a party that had nominated Dubuque for a seat in the legislature and Aram Pothier for the mayoralty of nearby Woonsocket. In Fall River, Greene could count on editor Misaël Authier, a Central Falls resident, who joined him on the campaign trail and helped refute allegations of anti-immigrant views.

Greene’s bid ended disastrously. A GOP rally at the Saint-Jean-Baptiste hall—in the infamous Flint Village—was disrupted by the guerrilla tactics of Coughlin supporters. Greene was put on the defensive; so was editor Adélard Lafond, who spoke up but had to admit that he was not a registered voter. One Joseph Amiot stated that it was Irish Democrats who had pelted Canadians with stones; he then expressed reservations about the religious sentiments of his political rivals.

Amiot was booed, Greene struggled to salvage his campaign, and, in the end, Coughlin was returned to office—thanks in no small part to the Franco-American electorate.

A new Democratic dawn in Fall River was not to be. Within months of Cleveland’s inauguration, the country entered one of its worst-ever economic crises—a deep industrial depression that would last through to the next presidential contest. The downturn brought economic issues like monetary policy and tariffs back to the fore. Democratic trade policies were blamed for the crisis and Fall River’s swing vote returned to its first home. In 1894, Dubuque campaigned for Greene, who reprised his role at city hall.

Faring poorly, the Democratic Party failed to recruit candidates—former mayor Coughlin, for instance—who might bring it back to life. That opened a momentary opportunity for Franco-Americans.

One month before the mayoral election of 1900, the Democrats had yet to pick their standard bearer. When the local nominating convention opened in November, the organizers struggled to confirm that all attendees were members in good standing. After four ballots—during which organizers left the convention hall for a late-night, last-ditch appeal to prominent Democrats across the city—piano manufacturer Edmond Côté won the nomination. The first Franco to earn such a nomination in Fall River, Côté might seal a new Franco-Irish coalition that would resurrect the party. But there was a catch. Côté was a Republican. Facing strong backlash from dedicated Democrats, he withdrew his candidacy days later. His political career was, at least, launched. A few years later, he sought his own party’s nomination. After a long career in business, he would again be a Franco pioneer by finding a seat on the Massachusetts Executive Council in the 1930s.

So what mattered to the rapidly growing Franco-American electorate? It is very telling that in 1892, the local French-language newspaper, L’Indépendant, offered its readers some math. Under Republican president Benjamin Harrison, 386 Franco-Americans had been appointed as civil servants. By contrast, the Democrats had only appointed 265 during the first Cleveland administration. The larger point is unmistakable: ethnic recognition—the visibility and influence of the group—mattered a great deal.

The world of late nineteenth-century politics was transactional and collective representation was a form of currency that could be exchanged for support at the ballot box. Americanization changed that: it exposed Franco-Americans’ own wide and divergent interests. Politics, we find out, was a key dimension of their acculturation.

In the early twentieth century, class dynamics asserted themselves and the Franco-American community splintered politically. Across the U.S. Northeast, the working class embraced organized labor on its way to becoming a pillar of the (Democratic) New Deal coalition. The middle class remained more firmly attached to the Republicans and suspicious of labor and government intervention.

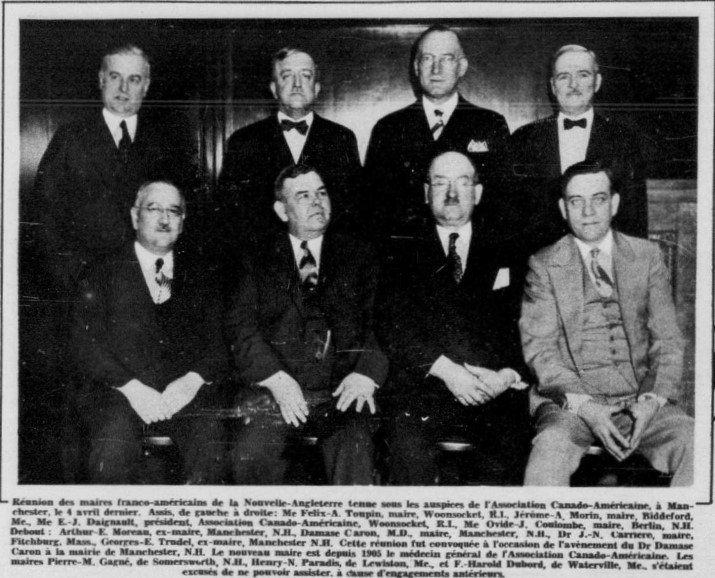

Ultimately, my study broadens our understanding of Franco-Americans’ collective action in this era; it also highlights the geographical breadth of French-Canadian culture and Franco political activity, carrying the narrative far beyond the “Crown Jewels” of Woonsocket, Fall River, Lowell, Manchester, and Lewiston. Talented researchers have drawn our attention to places like Worcester, Salem, and Brunswick in recent years. One can only do so much in 300 pages, but I hope that my exploration of small, regional centers like Plattsburgh, Rutland, Berlin, and Old Town will spark interest in the wider Franco-American world.

Leave a Reply