Research on Franco-Americans’ political engagement is still in its infancy. Major works on their politics may be counted on a single hand. The assumption is that the Catholic Church, cultural societies, and textile mills were more central to Franco-Americans’ self-definition and daily lives. Perhaps. But none of these spaces was hermetically insulated from the world of U.S. politics. While the naturalization campaigns slowly made inroads in the Little Canadas in the 1880s and 1890s and Francos made their way into municipal offices, community newspapers became increasingly interested in state and national politics—and increasingly partisan.

Francos were hardly ever unified politically, except at the local level, in the U.S. Northeast. In the early twentieth century, they tended to support the Democratic Party in the large industrial cities of northern New England (from the Merrimack valley northward) and the Republican Party in rural areas and in cities further south. But even these generalizations miss some fascinating local stories. Locally in Plattsburgh and Winooski, for instance, both parties could claim strong Franco involvement.

Research is complicated by the multiplicity of factors that dictated French Canadians’ involvement in mainstream politics and their local partisan allegiances, including:

- Big contemporary issues like local prohibition, tariffs, and economic slowdowns;

- Relations with other ethnic groups in the labor movement;

- Irish or “old-stock” Americans’ willingness to forge alliances with Francos and include them on the ballot;

- Nativism or religious antagonism;

- The interests and opportunities spied by Franco elites, including access to local liquor licenses and patronage;

- The size of the locality’s Franco population;

- The sudden appearance of maverick or wild-card candidates like William Jennings Bryan;

- Etc.

The major figures in turn-of-the-century New England are Hugo A. Dubuque, a state representative for Fall River and later a Massachusetts Superior Court judge, and Aram J. Pothier, mayor of Woonsocket and seven-term governor of Rhode Island. Both were born in Quebec; both have received well-deserved attention.

Other figures, however, have been obscured. One of them is Dubuque and Pothier’s rough contemporary, Benjamin Lenthier, who, unlike them, was a Democrat. The only scholarly study of Lenthier’s journalistic and political career, written by J.-André Sénécal, appeared nearly two decades ago as a chapter in an edited volume. It may be that the partisan attacks he suffered in his political career did lasting damage to his reputation. What’s more, he did not have Edmond Mallet’s military record, Dubuque’s constancy from one ethnic controversy to the next, or a position of public trust as elevated as Pothier’s. Both in his day and beyond, Lenthier was depicted as opportunistic, unscrupulous, and hypocritical, all too ready to serve others’ politics and his own pocketbook.

Lenthier was a native of Beauharnois, south of Montreal. He appears to have emigrated shortly after the end of the U.S. Civil War. One paper placed his naturalization in 1871; if doing this at the earliest opportunity, he would have arrived in 1866. He settled in Glens Falls, New York, and married Franco-American Julie Beaudette, who gave birth to at least nine children, though only three seem to have lived to adulthood.

Lenthier seems to have made a considerable living in the lumber trade, enabling him to pursue passions. In the early 1880s, he founded a French-language newspaper, Le Drapeau national, in Glens Falls. He then moved it to Plattsburgh and renamed it Le National. Appropriately, he began to take part in the national activities of French Canadians in the United States. He was one of the lead organizers and officers of the Rutland convention, in 1886, where delegates discussed naturalization, Louis Riel’s recent execution, and fall-out from the Flint Affair.

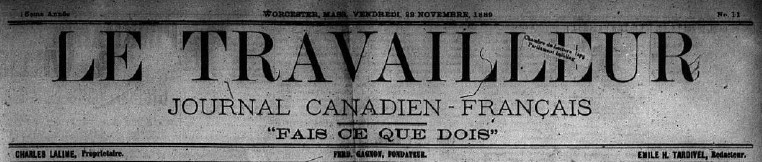

Around 1890, Benjamin Lenthier moved his paper again, this time to Lowell, Massachusetts. This brought him much closer to the heart of Franco-American life in the Northeast—and could bring him more subscribers. Through its three years as a daily, Lowell’s National had the largest circulation of any Franco-American newspaper. According to Alexandre Belisle, who authored a history of the Franco press, Lenthier’s paper “reached a degree of importance” not seen previously—even in Ferdinand Gagnon’s Worcester-based Travailleur.

Belisle was willing to acknowledge Lenthier’s success, but still characterized him as unscrupulous. He seemed to be no worthy successor to Gagnon, “the father of the Franco-American press,” even after he took control of Le Travailleur in 1891. In reality it was Boston Brahmin Josiah Quincy who had bought the paper from Gagnon’s brother-in-law before turning its editorial reins over to Lenthier, which no doubt did little to inspire confidence among traditional Franco elites.

Lenthier also acquired Manchester’s L’Avenir canadien and, as the country moved into a presidential election year, he began to consolidate something of newspaper empire. His acquisitions continued and he founded new, local editions of his flagship publication in Lowell. By November 1892, he seemed to control at least fourteen and maybe as many as seventeen Franco-American newspapers.

How could he afford to expand so quickly and seamlessly? His political adversaries quickly found an answer: party subsidies.

Next week: Benjamin Lenthier, patronage, and the Washington game.

Pingback: Corruption, Tariffs, and the French Vote (in 1892) - Query the Past