When the Irish men arrived they saw themselves displaced by the French who were occupying their usual pews. This situation did not endure for long, as the French worshippers, offering only minimal resistance, were forcibly dragged out into the aisles.

– Philip T. Silvia, Jr., “The Spindle City: Labor, Politics, and Religion in Fall River, Massachusetts, 1870-1905” (1973), 421.

Such was the outcome of a scheduling mix-up at the Church of St. Joseph, in Fall River, Massachusetts, one Sunday in 1887. Apparently a single Mass was to be celebrated, rather than one for each ethnic community as was customary. Physical altercations that defied religious strictures ensued.

French Canadians’ efforts to build new lives in a foreign land and to acculturate had local and personal dimensions, which are too easily obscured by religious debates that seem academic by comparison. An intellectual and elite focus is reinforced by historical actors who left the most abundant traces: newspaper editors and correspondents, delegates to ethnic conventions, leading members of civic organizations, etc. We can wonder about the relevance of community leaders’ activism to the everyday activities of non-elites.

The incidents retrieved by Silvia—including the disruptions of the Flint controversy—remind us of those real-world struggles of acculturation. They also complicate the story often told in textbooks and even immigration-specific histories, which depict immigrants’ efforts to overcome white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant nativism on American soil.

Certainly, some of these “old-stock” commentators worried about French Canadians’ growing numbers in New England and New York. Yet it is remarkable that the Canadian immigrants, for their part, complained little about native-born Anglo-Americans. With laser-like focus it is the Irish-American community that they blamed for their inability to acculturate on their own terms, that is, by melding their commitment to American institutions and their own inherited culture.

As noted, the Irish resented Canadian aloofness from a labor movement that they largely controlled; they opposed the dismemberment of their parishes to allow French-language rituals; they feared that new waves of immigration were setting back Protestant Americans’ grudging acceptance of U.S. Catholicism. Tensions boiled over in ways that often escaped newspaper coverage. On a Sunday morning in 1887, that resentment surfaced in the sacred space that ought to have made partners and allies of different Catholic groups.

Fall River was exceptional in many regards, but Franco-Irish conflict was not confined to Massachusetts or to southern New England. In the early years of the twentieth century, the Diocese of Portland, led by Bishops Louis S. Walsh, became Franco-Americans’ primary battleground.

Already disappointed that the New England bishops had overlooked qualified Franco-American priests when nominating Walsh to Portland, in 1906, the French-speaking population then objected to structural changes implemented by the new bishop. It seemed as though Walsh was pursuing administrative and financial efficiency specifically at the expense of Franco-American religious institutions—by merging parishes or closing schools, for instance. He could do so, critics explained, because the legislature had entrusted all Catholic property in the diocese to the bishop of Portland in 1887. The introduction of this “corporation sole” system had eliminated the parish councils that French Canadians had known for generations in Quebec.

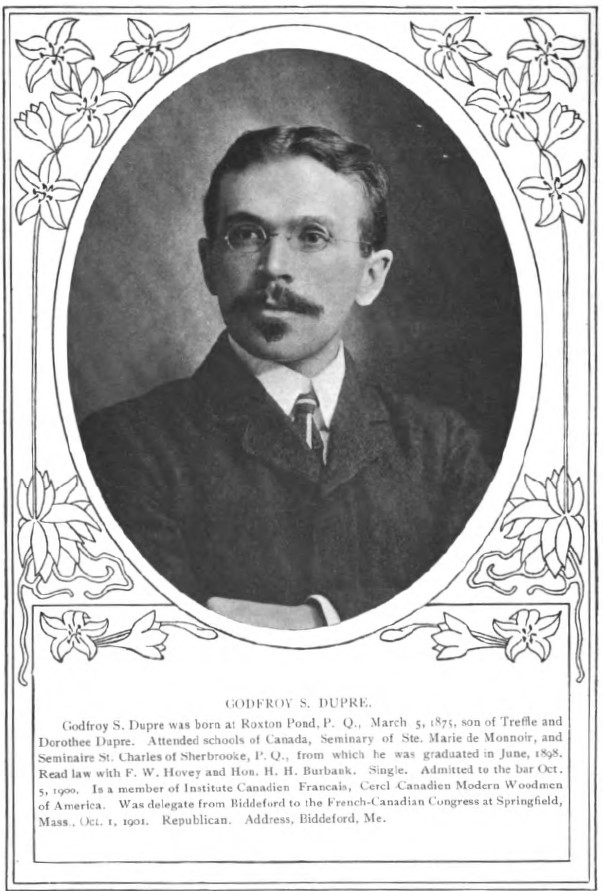

Initially, no major stir came of that measure, for then-Bishop James A. Healy (who died in 1900) understood and supported French Canadians’ aspirations. Two decades later, under Walsh, lack of control over national parishes, their revenues, and other Catholic institutions became critical for Franco-Americans. Attorney Godfroy S. Dupré, his colleagues on the Comité permanent de la cause nationale, and Maine’s French-language newspapers—Le Messager and La Justice—led a campaign for the abolition of the corporation sole. A widely-circulated petition supported their effort.

After testimony from Walsh himself, the legislature showed little inclination to change the legal regime. This, however, was not merely a civil matter. What did Rome have to say about the proper means of incorporating Catholic institutions, both generally and in the secular, republican landscape of American law? Franco-Americans pleaded for autonomy in their religious endeavors, arguing that the trustee system—with elected parish councils administrating all local Church property—would ensure control over their destiny in the United States.

The utter necessity of building bilingual schools wherever possible requires continued sacrifices, but that should not prevent us from shelling the corporation sole until its final collapse . . . I am not well, but every morning on my knees I pray to God that he may preserve me another few years, for I do believe that my mission, through the remainder of my earthly days, is the open, manly, and ceaseless struggle against the assimilator.

– Letter from Dr. J.-L. Fortier, quoted in “Waterville,” Le Canada français (June 23, 1911), p. 6.

The dedicated struggles of Dupré and others were not in vain, but their refusal to compromise could only produce disappointment with the ultimate outcome. When Roman authorities finally ruled, it was in favor of a mixed system. Parish councils were legitimate, but they should be composed of the bishop, his vicar general, the parish priest, and laymen chosen by the first three. There would be no such “lay socialism” as Walsh had feared. The bishop obtained from the legislature a new law that conformed to the Vatican’s instructions in the spring of 1913, spelling the end of the Franco-American campaign for religious autonomy in Maine.

The decades-long battle for cultural survival often masks the evolution of Franco-American strategies through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. First establishing ethnic parishes, the immigrants and their children then pursued a “national episcopacy” and eventually sought to reform the legal status of Catholic institutions in the United States. Lacking constitutional guarantees, Franco-Americans might build parishes into little fortresses in ways reminiscent of a later struggle for autonomy in Quebec.

Throughout the corporation sole controversy, Catholic bishops, administrators, and priests consistently worried about the scandal that French Canadians might be causing by voicing their grievances so publicly. On some occasions, the Canadians’ disregard for episcopal policies and orders—indeed, personal attacks on their spiritual guides—did seem to hint at “lay socialism” and to set an ominous precedent in relations with the Church hierarchy. It is little wonder, then, that Franco-American activists were deserted by some of their chief allies in Canada in the midst of the corporation sole controversy. A leading theologian, Louis-Adolphe Paquet, and the bishop of Sherbrooke, Paul Larocque, both condemned the tactics of discontented Catholics and called for obedience to American bishops, even in disagreement.

The distinctive political and cultural realities of Quebec and New England were also felt in other ways in the 1910s. For French Canadians and Franco-Americans, compulsory military service had a different meaning in Canada than it did in the United States during the First World War. Further, the campaign for “one-hundred-percent Americanism” in the U.S. illustrated the likely fate of francophones living through a time of resurgent nativist nationalism. Second- and third-generation Americans imbibed U.S. sports and movie culture and began to frequent dance halls.

These political and cultural factors were far more decisive than allegedly ill-intentioned bishops in the accelerating Americanization of French Canadians.

Nevertheless, the corporation sole controversy proves informative. In principle, Franco-Americans did not have to choose between the preservation of their language and customs on one hand and their Catholic faith on the other. National parishes and bilingual education survived early twentieth-century trials. Bishops and French-origin priests continued to engage in the community life of Franco-Americans. In fact, Dupré and his accomplices claimed to be living up to the Church’s own commitments. But, under Bishop Walsh, the threat of assimilation forced Franco-Americans to reconceptualize the identification of faith with nation that they had known in Quebec.

Further reading

P. Lacroix, “A l’assaut de la corporation sole: Autonomie institutionnelle et financière chez les Franco-Américains du Maine, 1900-1917,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, vol. 72, no. 1 (summer 2018), 31-51. Available on Erudit.

Leave a Reply