In a recent discussion of the Progressive Era, one of my students noted that scientists are ideally dedicated to the pursuit of a whole, unvarnished, and uncompromised truth, whereas activists are interested only in the truths that serve their cause. That may well be a fair portrayal of the social scientists and reformers of the early twentieth century. But, for scholars currently engaged in research on human populations, this distinction conceals the challenge of pursuing “truths” with empathy and understanding.

To put it in more concrete terms, in recent decades, Canadian scholars have sought to build a more inclusive, less Eurocentric narrative that does justice to the historical experience of Indigenous peoples. Andrea Eidinger, among many others, has blogged about the importance of placing First Nations voices, including oral traditions, at the center of any discussion of colonialism. The findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission suggest that we cannot address the present state of Native-settler relations without first confronting the types of stories we tell about ourselves.

Without making false comparisons to Indigenous history, we can wonder how scholars should intersect with the lived experience of historically marginalized communities—and whether the importance of privileging contemporary voices applies equally elsewhere. These are significant questions for anyone studying Franco-Americans, including yours truly.

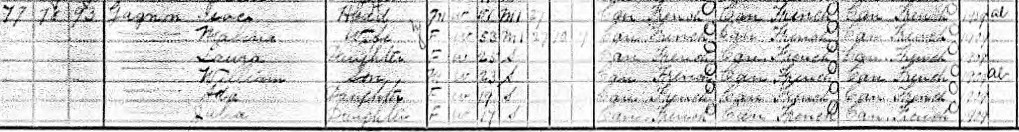

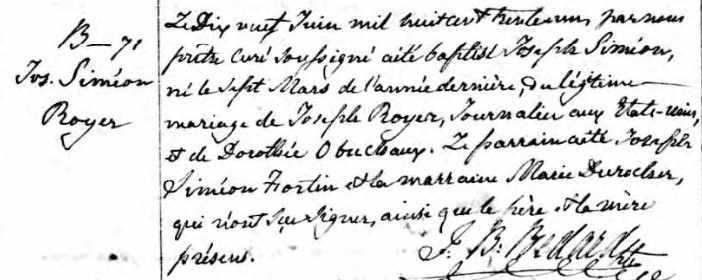

I am a “Generation 0” Franco-American, a Canadian who may, like his great, great grandfather, return to the homeland with a pocket full of U.S. specie. I am a historian first and I research Franco-Americans to develop a more historically honest, comprehensive, and balanced narrative. I bring my characters into the classroom and draw them out in my research. On the surface, this is rather different from the dedicated efforts of community members who strive to preserve customs and traditions, defend the community’s interests, or help to ensure its survival.

However, I cannot but be influenced by the historical narratives that structure Franco-American self-conceptions; Franco-Americans, for their part, will interpret my work on the basis of their collective memory. As I have previously argued, I am not merely in conversation with the dead, in my research.

The question thus remains: How much of the contemporary community should make its way into my work, and what bearing should my academic work have on the community, if any?

Insofar as this is a question of method, I confess to a certain skepticism when encountering oral history—a healthy attitude, I would hope, skepticism being at the heart of any honest inquiry. But, as scholars of Canadian history cannot afford to dismiss contemporary Indigenous voices, neither can I ignore my historical subjects’ descendants and broader legacy. In their great diversity, present-day Franco-Americans (whether self-identifying or not) are living evidence of the French-Canadian diaspora. As such, they remain an integral part of this history—they tell us of the factors which, generation after generation, brought the community to its present state. Their stories are, very often, a century in the making and capture something of their distinct experience. From a historian’s perspective, their stories can and should be historicized.[1]

In their pursuit of truth, however inaccessible, historians should challenge orthodoxies, les vaches sacrées, and bring forth evidence that conflicts with the memory of lived experience. Activists should take steps to anchor historians in the lived legacy of the Franco-American past; they should take action when historians might retreat from a worthy cause.

Occasional friction arising from different goals should not bar conversation and understanding, but encourage them. Like two mules in Nebraska, conceiving of rather different destinations, academics and members of the Franco-American community should continue to nudge one another, urging one another on—here, in the direction of justice in our day, in the direction of an honest portrayal of our past. This means withdrawing from the debate as to who has the whole truth, or useful truths, and approaching one another with charity and humility.

I suspect that this open, inquiring approach will guide a new effort to capture the vast array of voices in the Franco-American “Acade-munity.” Readers may already have heard of a forthcoming podcast on Franco-American life. Host Jesse Martineau plans to raise the big questions: What is a Franco-American? Are there multiple definitions? Is there a distinctive Franco-American experience? What are the past, present, and future of the Franco-American community in New England? What debates are animating this community? Such questions are a shared concern of community members and academics and will no doubt encourage greater outreach in both directions.

Alongside David Vermette’s recent monograph, new avenues of scholarly research, talks and events organized by community groups across New England, and equally stimulating blogs, this podcast suggests that Franco-Americans may no longer be on the margins of the region’s historical consciousness—a happy prospect for all. Check out the French-Canadian Legacy Podcast, and its social media links, here.

[1] That is, historians should treat these stories as fragments of the past, to be studied and analyzed critically in light of their context.

Leave a Reply