Unless you are particularly generous with your time and opinion, if you have ever posted a Yelp review, it is likely that you were commenting on a bad experience. For most of us, it is much easier to complain about misfortune, and act on it, than to express appreciation or bestow praise.

Through years of research, I have come to see correspondence in Roman Catholic archives as a kind of Yelp for believers and occasional outsiders—I have come to see archives as a site of grievance. Few historical actors represented in those archives seem to have put pen to paper to offer words of support. Priests complained about insubordinate and impious parishioners, and lay people went over their pastors’ heads and presented remonstrations to the Church hierarchy. Bishops somehow had to keep clergy and laity happy; ensure that the coffers were full and churches staffed by competent and upright priests; provide for the sound financial management of parochial schools and charitable endeavors; quell nativism and anti-Catholicism; satisfy the aspirations of various ethnic groups; regularly visit the parishes of their diocese and dispense sacraments; and, on key anniversaries, attend elaborate ceremonies. There was ample reason to complain.

Historical actors’ grievances are scholars’ gain. If, empathetically, we deplore that there were grievances in the first place, those actors might rest easily knowing that their words and deeds have transcended time. Surviving items enlighten our past. There is nothing quite like plunging into archives to understand how our predecessors thought and acted. Catholic archives especially provide an opportunity to uncover truths that evaded the attention of the contemporary press.

I offer the following insights on Franco-American history gleaned from my research in diocesan archives. For reasons that will become clear below, I do not mention the archival location of specific items.

Franco-Americans and Their Bishops

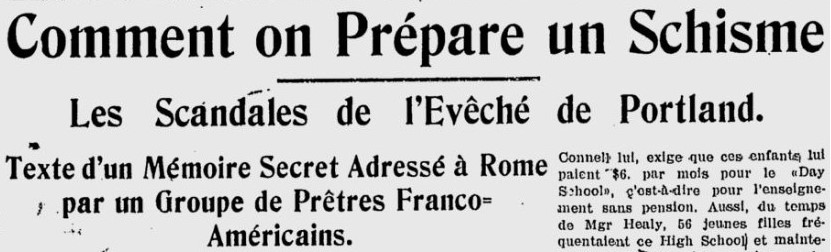

By focusing on militant ethnic newspapers in the Northeast, especially the Franco-American and Irish American presses, historians have long known of conflictual relations within the Catholic Church. But journalists were wont to misinterpret the inner affairs of the Church, first, because they derived their influence from their ability to rouse passions and, second, because bishops and chancellors operated discreetly in all matters of diocesan administration.

Any substantial glance at the private writings of Catholic bishops reveals that they were not animated with the assimilationist zeal—seemingly their only preoccupation—often attributed to them by the press. Quite the opposite: French-Canadian immigrants were contributing mightily to the Church’s growth in the Northeast and the hierarchy recognized that some accommodation would be needed to ensure that the newcomers did not desert the Church entirely.

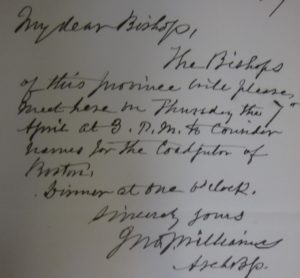

Thus we learn that John J. Williams, a long-time archbishop of Boston, spoke French and could write it just as well when circumstances called for it. Matthew Harkins was preferred as a bishop of Providence partly because he too knew French and was more likely to appease the concerns of Franco-Americans in Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts. James A. Healy, the first African-American bishop in the U.S. Church, held the episcopal seat of Portland, Maine, for a quarter of a century; throughout his tenure, he corresponded extensively with clergy in Quebec, including the bishop of Sherbrooke, where his (Healy’s) sister resided.

In short, though some bishops were less eager to preserve distinctly French-Canadian churches and schools, my archival findings suggest that the source of conflict lay seldom with the Catholic hierarchy. Rather, we should look to Irish “Americanizers” seeking to overcome religious prejudice among Protestants and to enroll migrant Canadians in the ranks of a cohesive labor movement. In both regards, the Irish, their press, as well as their “labor priests” exerted great pressure on Francos to assimilate.

Franco-Americans and Their Priests

Archives provide a glimpse into the character and abilities of men whose failings were omitted from contemporary published works on American Catholicism. Naturally it seems as though the least visible men in diocesan correspondence and reports were the most honorable and capable.

Ill-behaving clergymen were not always brought to bishops’ attention by alienated parishioners. One terrible case that has not been erased from history concerns a nineteenth-century priest who was accused of physically abusing a boy in Granby, Quebec, and who expected imminent criminal charges. The prelate’s friends in Canada sought to avoid a scandal by having him quietly transferred to a Catholic parish in the United States. A cryptic letter in the same folder suggests that their efforts may have been successful.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Catholic Church in Lower Canada and then Quebec bounced back from the priest shortage it had until then experienced. For its part, New England needed new clergy to serve its quickly growing population of Catholic immigrants. Bishops in the region sought to obtain priests from Canada. It may be that episcopal figures north of the border were not sending their best and brightest; it may be that their American counterparts could not afford to pick and choose. Did New England become a dumping ground for Quebec priests who behaved badly? The abovementioned item and several others like it point in that direction, but we should be lenient in our overall assessment: likely few laypersons ever wrote to their bishop to comment on the perfectly adequate work performed by their pastor.[1]

The Franco Laity

If some Protestants were (and perhaps still are) inclined to depict Roman Catholics as meek and unthinking, perpetually crushed by the authoritarian rule of bishops, Franco-Americans’ historical experience suggests quite the opposite. Religious controversies stemming from their “national” aspirations were, indeed, many: the Flint Affair (1884-1886), the Cahensly question (1889-1890), conflicts in Danielson, Connecticut, and North Brookfield, Massachusetts (1894-1900), the Corporation Sole controversy (1909-1913), and the Sentinelle Affair (1924-1929). This is omitting smaller and generally briefer confrontations over Franco-Americans’ ethnic identity in various localities. The supposedly clannish, obedient, and unquestioning Francos were an extremely disruptive presence within the U.S. Church.

Communities did not circle the wagons merely to have their distinct culture recognized, however. In one town in northern New England, prominent Catholic men wrote to their bishop on behalf of daughters and female acquaintances, who complained of a priest’s inappropriate behavior towards them. If the case of child molestation mentioned above is dispiriting, here the process of contestation and its outcome provide some solace. When one woman reported the clergyman’s solicitations to another priest, the latter asked her to report the matter immediately to the bishop. Another woman wrote to the bishop to defend her husband from lies spread by the priest. Families and communities banded together to uproot a bad seed; they utilized all religious and legal means—here too the matter was nearly brought to court—at their disposal.

Compassion and discretion

Archival research often entails revealing to the world thoughts and actions that historical actors sought to keep private—bishops who would want to prevent scandals, but also ordinary men and women who were concerned about their personal welfare and reputation. We cast our gaze on past lives for our present purposes, typically without the consent of our forebearers.

One especially heart-wrenching case that I came across haphazardly concerned a young woman who had gotten pregnant as a fourteen-year-old girl. She found it impossible to live with the man she was made to marry and they separated. Despite their devotion to one another and shared commitment to the Catholic Church, this woman could not marry the father of her second child; the Church would only ever recognize the first marriage. The woman’s six-page appeal to the bishop, a letter of profound sincerity that today arouses the most profound empathy, was seemingly made in vain. The bishop asked the woman to turn to her local parish priest, who (in an odd bureaucratic twist) would decide whether it might be a matter for the diocesan tribunal.

Though this woman was evidently of Franco-American heritage, I did not have to ponder some of the more difficult questions of archival research. The case was not directly related to the research I was then conducting and, because she might still be living, I would never consider disseminating information that would break her anonymity without her direct consent.

But what of the alleged victim from Granby? Do the deceased have a right to privacy? Should their descendants have a say? Do the benefits of a better understanding of the past outweigh the moral dilemma posed by “peering” despite the author’s original intent? Should famous figures like Archbishop Williams be considered differently than our Jane Doe?

Even if my research on Franco-Americans typically does not wade into questions of personal morality, I do wrestle with these questions and must frankly admit that I have no easy answer—unless it is to remind myself that I should approach a new opportunity (for the advancement of knowledge especially) by first exercising empathy. Indeed we should all ask ourselves: Am I doing justice to the historical characters and situations that I wish to describe?

I am a firm believer that one of the great virtues of historical learning is the possibility of opening one’s mind to difference. By viewing others in their respective circumstances, both as products and as agents of those circumstances, we may become more compassionate when approaching our contemporaries. Before we can undertake that heady work among our students, however, I think we, historians, must apply that principle in our own work and show compassion for those who can no longer speak for themselves.

This sizeable task, I hasten to add, is complicated by the particular challenge posed by the archives of such an institution as the Catholic Church. Scholars have no essential right to access private archives; if they misrepresent the organization that they are researching—or represent it fairly but cause scandal—they may be jeopardizing their access to those resources. They may be closing avenues for further research for themselves and fellow scholars.

I conclude, then, by summarizing my approach:

- Stick to the essentials of your research topic and avoid the alluring tangents presented by noteworthy, but unrelated, archival items.

- Avoid identifying an entire organization with the failings of specific people.

- Establish a trusting rapport with the archivist, one that will enable you to make the most of available resources—and may pay dividends in unexpected ways.

- Amid all of the above, do not sacrifice your integrity as a moral being, a citizen, and a scholar, hopefully in that order.

[1] Nor were the priests’ failings always in the realm of sexual immorality. One enlightening case is that of a French priest in the Diocese of Portland whose extravagant spending plunged his parish into great debt. His refusal to heed his bishop’s orders extended the problem and ultimately led Healy to demand legislation providing him with full legal control over Church property in Maine.

Leave a Reply