We are less than two weeks away from the third Young Franco-Americans Summit, an initiative launched by the Franco-American Centre in Orono, Maine, in 2021. This year’s YFAS will be held at Rivier University in Nashua, New Hampshire, and, like prior installments, it will connect Franco-Americans in their teens, twenties, and thirties around common cultural concerns. This type of opportunity to build solidarity and provide inspiration in a supportive, collegial environment is a fairly novel initiative in the multicentennial history of Franco-Americans. Yet, young people have shaped—or have sought to shape—their community from the time French Canadians first set foot on U.S. soil.

For at least half of that time, youth looked a lot different from what it entails today. In working-class households across North America, in the nineteenth century, children and teens were full-fledged members of the family as a basic economic unit: they fulfilled productive tasks that assisted and complemented their elders’ work. In Lower Canada (later the Province of Quebec), youths were involved in most aspects of farm life. Although the type of work differed substantially, child labor in Northeastern factories fit within the same logic. Young people contributed to the household economy not only as a tradition or an obligation, but as a necessity.

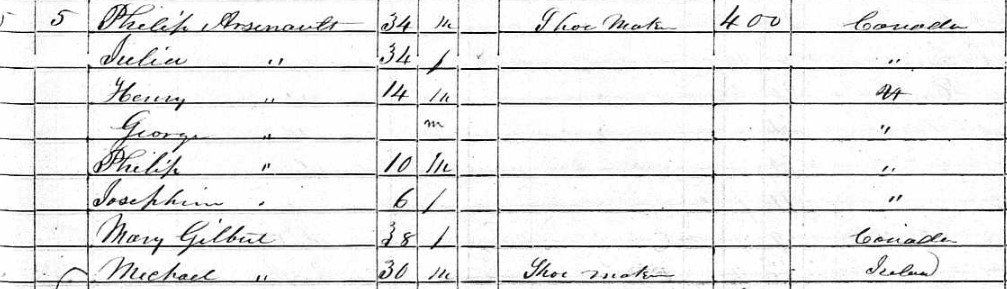

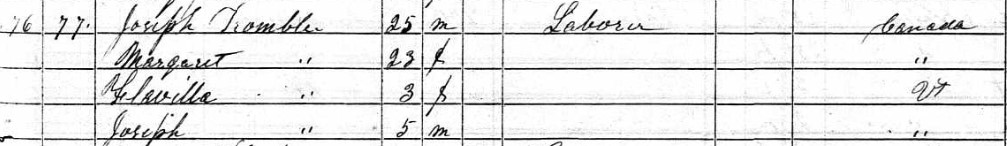

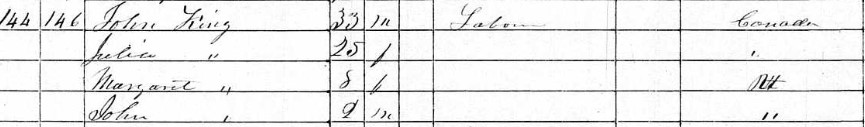

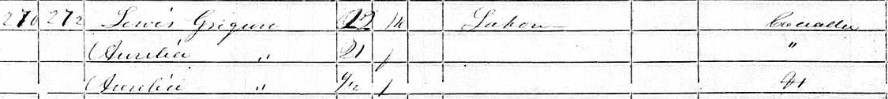

When youths appear in histories of Franco-America, it is typically in this context of industrial labor. One easily forms the image of a community dominated by middle-aged parents and the grey-haired priests and leaders of institutions nationales. There is some truth to that, but there is much more to the picture. Young couples were well represented among the French-Canadian households of northern New York and Vermont—some of the earliest migration fields—in the 1840s and 1850s. Young men lived momentarily in boardinghouses and ordinary homes while seeking short-term opportunities in the United States. Carried by desperation, adventure, or ambition, countless men earned wages and acquired cultural capital that facilitated a more lasting presence south of the border.

This is to say nothing of the youths who sought a faster path to financial independence by serving in the armed forces of the Republic during the Mexican-American War and the U.S. Civil War—or by panning for gold some 2,500 miles from home. Young people were willing to push the physical boundaries their nationality until then knew. From the St. John Valley to San Francisco, they planted seeds for new communities.

They pushed boundaries in other respects. Migrants aimed to experience their adoptive country on their own terms. From the late 1870s on, young professionals and merchants organized their compatriots in common cultural endeavors. The most prominent and influential community leaders of the 1880s, including Hugo Dubuque, Omer Larue, and Louis J. Martel, were all under 40 years of age. Famously, Ferdinand Gagnon, soon to be known as the father of the Franco-American press, had been the editor of Le Travailleur for twelve years when he passed away at age 36.

Other pioneers followed—and not merely war heroes and athletes, whose youth is usually assumed. For instance:

- Eva Tanguay, at one time the highest-paid vaudeville star in the country, was touring before the age of 20.

- Camille Lessard (later Bissonnette) was 27 when she held her own in a local debate on the merits of female suffrage. She died in 1970.

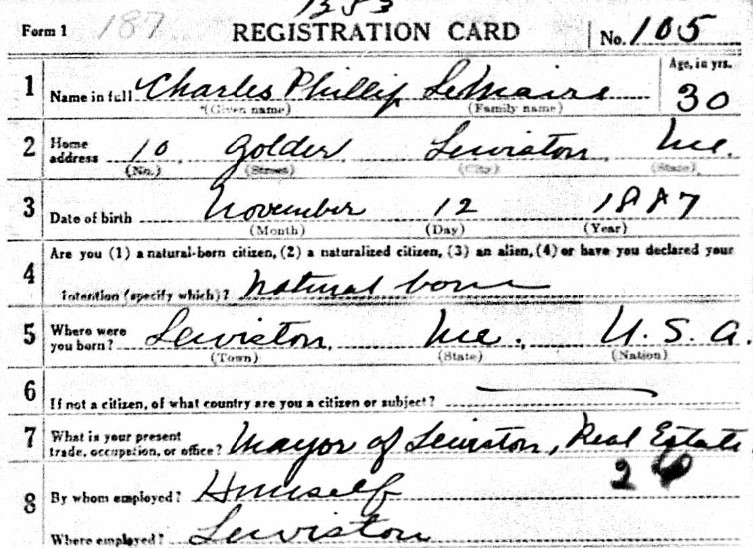

- Charles Lemaire, a real estate dealer, became mayor of Lewiston—the second Franco-American to hold the office—in 1917, when aged no more than 30. He also lived to see the 1970s.

- Adrien Verrette, whose father became mayor of Manchester in 1917, was ordained to the priesthood at age 23 after studying in Sherbrooke, Worcester, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. He served as vicar in New Hampshire parishes and soon embarked on a long publishing career.

- Grace Metalious’s scandalous Peyton Place appeared in print when she was 32.

Many of the young people who grew up in Franco-American communities in the early decades of the twentieth century had, at best, a tenuous connection to Quebec. Some visited relatives with their parents. But their social and cultural universe was now completely different. American sports and entertainment crept into ethnic neighborhoods and into Franco-American homes. In many ways, the real architects of Franco life were not the immigrants, but the next generation—young people at the meeting of two worlds who had a part in creating a unique, hybrid identity, which meshed bilingual education and le réveillon with exciting new films and American Legion meetings.

Over time, the culture swayed farther from its Quebec roots. The changing institutional landscape of Franco-America from the 1950s to the 1980s had clear effects on young people’s ability to negotiate questions of identity. The old institutions of survivance were slowly dismantled as middle-class Franco-Americans joined organizations that offered similar benefits on a non-ethnic basis, moved out of ethnic neighborhoods, and embraced mainstream American culture. Some were eager to break out of a sheltered community that seemed to belong to an older generation—a generation little interested in passing the baton and whose cultural touchstones were of a different era.

Outside of areas with a majority-French population, university campuses gradually became the main sites of cultural encounter and cultural activity among young Franco-Americans. Across New England, professors of French-Canadian descent (a relative novelty in the 1970s) taught French and helped youths better understand and appreciate their heritage. Still, not all campuses generated the same fervor. The University of Maine in Orono was something of an outlier in the intensity of Franco renewal it experienced.

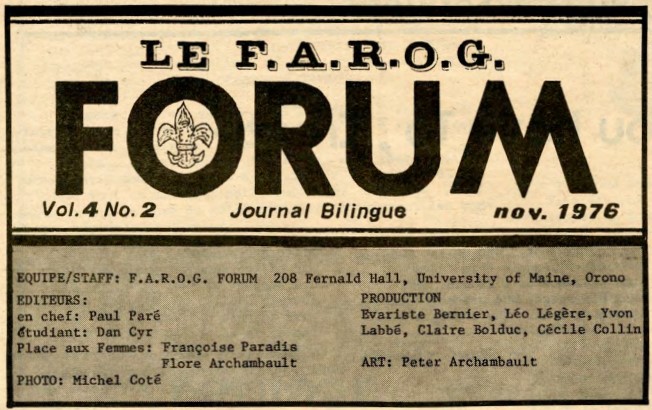

The civil rights movement, anti-war activism, and second-wave feminism inspired young people to take action in their communities. This sense of agency helped mobilize highly motivated individuals to make Franco-American life their own—to grab the baton. In Orono, the informal student meetings of the 1960s led to conversations with university administrators and faculty. Students formed the Franco-American Resource Opportunity Group (FAROG), which has now been in existence for more than 50 years, and founded a long-lived publication now simply known as Le Forum. Claire Bolduc, Ludger and Steffan Duplessis, Céleste Roberge, and many others created a space where none had existed. Others would bring fresh perspectives to the Fédération féminine franco-américaine and the Conseil de la vie française en Amérique, though not without facing considerable obstacles.

The Franco-American world of the Northeast has experienced a similar period of renewal and revival in the last six years. Those leading the charge are again, to a great extent, people in their twenties and thirties. Undeterred by grumbletonians and gloom-and-doomers, they expect to have a say in the future of their community. They understand that any living culture changes and adapts. Attuned to new social and political issues, they are also setting themselves apart by turning to new technologies, including social media, blogs, and podcasts. Like their predecessors, they are creating spaces where none had existed. PoutineFest and the Young Franco-Americans Summit are but a few examples.

Amid these advances, there are lingering questions to be addressed if this period of renewal is to be lasting. To what extent have young people been invited into existing organizations, activities, and conversations? If invitations have missed their mark, have we considered why—in a way that doesn’t simply cast youths as apathetic? If they aren’t interested in cultural questions, why is that? How can we empower them?

There is no easy solution, but whatever answer may be found can only come from engaging meaningfully with and listening to the people who can carry the culture into a distant future.

Interesting read….Lest we forget those F-Cs who emigrated to newly created States like Michigan and Minnesota and Wisconsin in the mid-1800’s as well. Would be good to have some articles that refer to this westward migration, particularly after the American Civil War period….