See Part I here.

As Cohoes Franco-Americans became more numerous following the Civil War, they attracted the likes of Ferdinand Gagnon, who helped to bring the community into a larger Franco world. They also produced their own luminaries. Joseph LeBoeuf was one pioneer who anticipated the role that Hugo Dubuque and other attorneys would play in centers farther east. LeBoeuf’s family had moved to the U.S. in 1847; he was admitted to the bar and practiced law in Cohoes. In 1869, he was elected to a local judgeship. He served as founding president of the local société Saint-Jean-Baptiste and helped to organize the parish of St. Joseph. He represented Cohoes French Canadians at state and regional conventions and became an appreciated orator.

In 1877, LeBoeuf ran for local office under the Greenback-Labor banner—and received twenty-one votes. He moved to Holyoke shortly thereafter and, eventually, to Chicago. He died in 1909.

Another attorney, Jean-Georges LeBoutillier, settled in Cohoes in 1890 and became Benjamin Lenthier’s local newspaper agent during the following presidential election campaign. LeBoutillier, a staunch Democrat, soon joined Lenthier in Lowell, and when journalistic opportunities there dried up, he went on to Fall River. He carried his encounters with working-class life in Cohoes to subsequent reporting on immigrant labor.

The torch was soon picked up by another Quebec-born attorney, Israël Bélanger, who was also deeply involved in the life of his cultural community. He became a judge in 1908 and then worked in the state attorney general’s office.

Ethnic institutions provided men like Bélanger with the opportunity to develop their skills and with an organizational network that could help them succeed in the larger civic world. In early-twentieth-century Cohoes, those institutions were positively vibrant. In 1908, the community—with Bélanger doing his part in the planning—celebrated the fortieth anniversary of its société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. A banquet drew several hundred distinguished guests, including a justice of the state supreme court and mayor Merritt D. Hanson. Also present were prominent Franco-Americans Adélard Archambault, the former lieutenant governor of Rhode Island, David Lavigne of La Tribune (Woonsocket), and J. C. Hogue from New York City’s société. Governor Charles Hughes addressed the assembled Francos at the end of their procession on June 24.

Cohoes Franco-Americans’ identification with their parish institutions was in full view during that anniversary celebration. In the decades that followed, the Catholic Church remained the heart of the community. On the eve of the Second World War, over a thousand pupils attended the national parishes’ denominational schools, where half-day French instruction continued to prevail. Through the Church, through the two world wars, Cohoes Franco-Americans negotiated the challenges of acculturation, of melding faith, ancestry, and American patriotism.

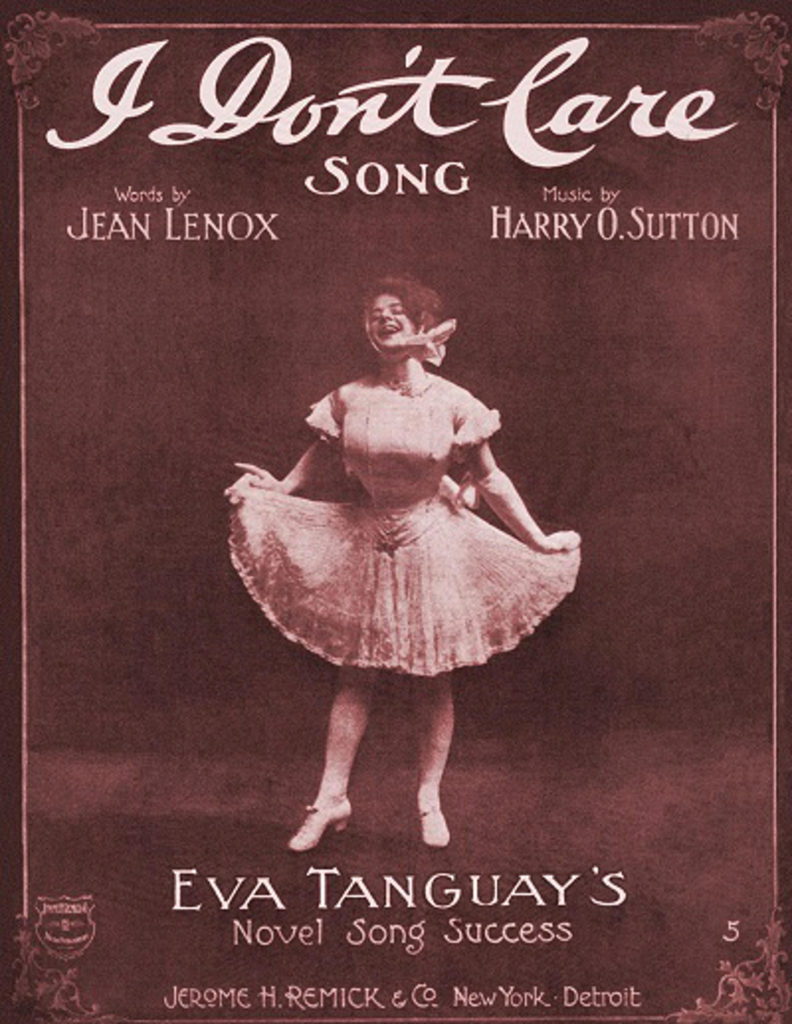

There were, of course, other points of intersection with mainstream American life and culture. Eva Tanguay exemplifies one of them. Tanguay—significantly, a woman and an entertainer—represents Cohoes’ chief claim to fame in the larger annals of Franco-American history. She was born in Quebec and grew up in Holyoke, Massachusetts, which also claims her as an adoptive daughter. But it was at the Cohoes Music Hall that Tanguay made a name for herself. Her outrageous costumes, playful attitude, and salacious vaudevillian performances brought her packed audiences, celebrity, and wealth.

She would eventually die in destitution in California, but some believe that her soul survives in Cohoes, where she lived her happiest days. At the very least, do not expect to wander through the Music Hall alone.

Popular entertainment and sports spoke something of a universal language that helped to draw Franco-Americans into a larger American world. They also engaged with their adoptive country through politics, and not merely through their leading figures and (we’re looking at you, LeBoeuf) their occasional quixotic campaigns. In the last third of the nineteenth century, there was little separation between Cohoes manufacturing interests and the high-tariff Republican Party. It was not unusual for mill officials to run for some municipal office under the GOP banner. If there is little evidence of acute conflict between the Irish and French Canadians, the city’s two dominant ethnic groups still diverged politically following the Civil War.

Whereas in major cities of northern New England, a Franco-Irish marriage of convenience formed in the Democratic Party, in Cohoes—as in other areas—the Canadians tended to support the Republican Party. They often formed their own Republican political committees in the lead-up to local and national elections. It seems they were able to separate their labor activism (and a bid for better working conditions) from a broader political vision, which they entrusted to elite industrial interests.

From the turn of the century to the Great Depression, acculturation and growing solidarity in the fields of labor and civic politics gradually brought Cohoes Franco-Americans into the Democratic fold. Although more research is needed in this regard, we may speculate that Francos’ partisan shift helped Democrats capture the mayor’s office in the early 1920s. The Democrats—informally led by “boss” Mike Smith—would hold the city’s reins for over forty years. Quebec-born Rudolph Roulier, whose blue-collar roots proved no barrier to economic and political success, became a state legislator and served as mayor for two decades, setting a record for longevity in that office. But, in the early 1960s, the woes of deindustrialization, urban decay, allegations of corruption, and voter fatigue led to the rise the Citizens Party, which displaced the Democrats.

Industrial decline was by no means novel in the postwar period. But the situation became more dire and definitive as the textile sector had its last gasp. Some families struggled to adapt; others, perhaps already in a steadier situation, took advantage of wartime income and the G.I. Bill to move up and move out. Acculturation reached its apotheosis as Franco-Americans found new ways of supporting themselves and began forming new social networks.

Old community bonds loosened. But some residents remained committed to the preservation of French-Canadian culture and local Franco history. Like Eloïse Brière, Quebec native Bernard Ouimet has done a great deal to bridge two generations or phases of Franco-American community activity. Ouimet was a social studies teacher; he helped to found and has led the Fédération franco-américaine in addition to his contribution to the life of St. Joseph’s church as an organist. His research and talks have proven essential to the preservation of the local Franco story, to be taken up by the next generation of scholars and history enthusiasts.

New York State’s French history is extensive, complex, and rich in potential insights. There is still a considerable need to bring local stories into a larger whole without erasing their idiosyncrasies—their unique and fascinating twists. Local history is too important to remain local. We may hope that additional attention to the Franco-Americans of New York City, Rochester, Ogdensburg, Malone, Whitehall, and of course Cohoes will lead to greater appreciation of the “ethnic factor” in the history of the Northeast.

Sources

Aside from the sources explicitly mentioned or linked in both installments, I used contemporary sources from Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, the Library of Congress, and Newspapers.com. Alexandre Belisle’s history of the Franco-American press has also proven indispensable.

Very interesting, your article filled in many questions I had. My great grandfather immigrated to Troy, NY from Quebec, Canada in 1885, and later moved to Cohoes, where he worked for the textile company A.G. Peck, until his death in 1890.