I am not without hopes, however, that later some one may assume this task, and cause the social and literary activities of those days, and the participants therein, to live over again.

– Prosper Bender, Quebec Daily Telegraph, June 29, 1907

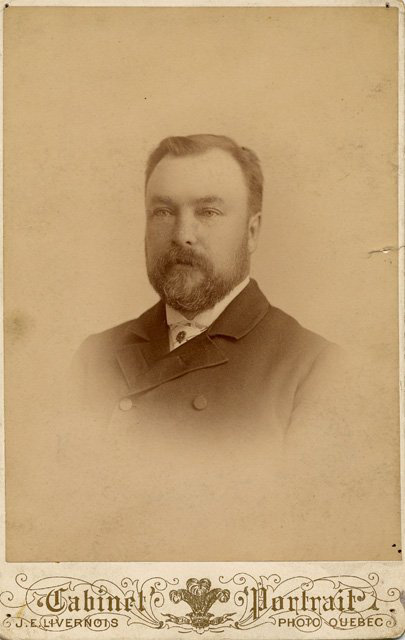

As the son of a prominent attorney in Quebec City, young Prosper Bender could expect a bright future. He learned English at home and mastered French at the Petit Séminaire. He went on to study medicine at McGill University and could one day aspire to public service. But Bender carved his own path. Too young to earn his medical license after completing his degree, he served with the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War. Several years later, at a time when the Canadian Medical Association was refining its professional standards, he was expelled for advertising homeopathic treatment. Most significantly of all, Bender became the synapse of the province’s flourishing literary culture.

In the 1870s, in what became a Sunday evening ritual, Bender welcomed some of the greatest writers of the day—Oscar Dunn, Faucher de Saint-Maurice, Hubert LaRue, Joseph Marmette—and influential politicians at his home on rue d’Aiguillon in Quebec City. Guests talked of past adventures and current events; they also tended to the creation and critique of French-Canadian literature. Bender did his part for the cause. In 1881, he penned Literary Sheaves, designed to promote awareness and appreciation of French-Canadian authors, many being close friends of his, among English speakers.

The following year, Bender wrote Old and New Canada, a meandering biography of his great-grandfather, Joseph François Perrault, meant to revive days long past. Both books contained powerful expressions of Canadian patriotism. What ensued was thus all the more jarring. At the height of literary influence, Bender again left Canada. He settled in Boston, where he resided for the next twenty-six years of his life.

Bender’s move came at the apex of the grande saignée, the great demographic hemorrhage from Quebec. Tens of thousands were leaving the province yearly to take up work in New England factories. The middle-aged physician had other interests and steered well clear of the Little Canadas. From the comfort of the Hotel Vendome in downtown Boston, he immersed himself in an exciting new cultural universe. His fascination with the United States did not suddenly cool. A decade later, while still singing the praises of Boston, he was naturalized.

Bender continued to practice homeopathic medicine and write. He quickly lent his pen to the cause of continental economic union and American annexation of Canada. We need not look far to find the reasons. Premier Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau of Quebec had recently resigned as a result of a corruption scandal. John A. Macdonald’s “National Policy” had yet to pay substantive dividends and the economy struggled. The costs of national development were rising, as were taxes. Animosities between French and English added to Bender’s pessimism. The North-West Rebellion soon served as a case in point.

Less intransigent than fellow annexationists Louis Fréchette and Goldwin Smith, Bender proves an interesting bellwether of national development in the late nineteenth century. Like other Canadians, he could not know with complete certainty whether Confederation would offer its promised fruit and whether Canada would survive as a political project. But when a continental economic union was decisively rejected in Ottawa and in Washington at the dawn of the 1890s, Bender laid his grand idea to rest.

Still, he remained in the United States and continued to work as an interpreter of French-Canadian culture, now among Americans. He contributed numerous articles to magazines in hopes of curbing the winds of nativism and interethnic resentment. In fact, in the 1880s and 1890s, he was the leading English-language writer on French Canadians in the United States. His work as an intercultural broker on both sides of the border cannot be overlooked.

Burnt by professional reversals, wracked with nostalgia, Bender returned to Quebec City in 1908—his faith in Canada apparently restored. As the product of a different era, he spent his later years looking back on the literary scene of which he had been the centre. Spurred to action by his old friend William Blumhart’s death in 1907, he contributed over thirty articles detailing that flourishing scene to the Quebec Daily Telegraph through the next two years. He resumed work of this kind with a series of biographical sketches, also for the Telegraph, in 1914.

Bender died in 1917, on the eve of yet another national crisis. His own role in Canada’s evolving national drama had long past. He nonetheless remained an exemplar of Canadians’ enduring fascination with the United States—and reflected the many shoals that awaited his native land for decades after the British North America Act.

More than a century after Bender’s death, Canada is a much stronger country and its neighbour has lost much of its varnish. In the era of President Trump and American economic nationalism, we might be excused for searching—apparently in vain—the Canadian mind for the alleged lure of the United States. That distinct fates awaited these countries could not seem more natural.

Bender comes as a valuable corrective to that teleological view. The enduring fascination was not always—and need not be today—a self-congratulatory and condescending gaze. For generations, Canadians avidly turned to the Great Republic for cultural and economic capital that they could not access in their home country. In the first fifty years after Confederation, even amid well-meaning efforts to build good will and to nourish Canadian patriotism, the lure of the United States was in direct tension with the many controversies and challenges facing the young country to the north.

You can learn more about Prosper Bender in this article in the Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 52, no. 2 (spring 2018), 381-403.

Leave a Reply