The main lines of John F. Kennedy’s life are widely known: his heroism in the Second World War, the hotly contested election of 1960, alleged moral failings ranging from infidelity to equivocation on civil rights, the Bay of Pigs disaster and the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the tragic turn of events in Dallas.

But for many years we have been missing a big piece of the puzzle. Kennedy’s time in office witnessed a significant and enduring transformation of the country’s religious landscape. New research reveals that the first Catholic president was an agent of religious change who forced encounters on a scale unsuspected until now. His time in office — and not merely the turbulent campaign of 1960 — proved to be an important moment in the transition from the postwar religious revival to political coalitions that are still with us today.

Read more in John F. Kennedy and the Politics of Faith, the first major study of the meeting of faith and politics under the 35th president, now available from the University Press of Kansas.

Praise for John F. Kennedy and the Politics of Faith:

For a sneak peek of my research on the religious legacy of the 1960s, please see the following:

“How Estes and Ike Transformed the New Hampshire Primary – And How JFK Defined It,” History News Network, June 23, 2019.

In the last sixty years, the Granite State’s first-in-the-nation primary has crushed the ambitions of many a presidential hopeful – including incumbent presidents. The nearly two dozen Democratic candidates now descending on New Hampshire understand this all too well.

The state did not become a force in national politics simply because it is the first presidential primary. It was made by presidential candidates who could only glean victory by challenging backroom politics and party bosses. Instead of courting likely state delegates to party conventions, outsiders sought the support of rank-and-file members. As a result, in the 1950s, the blessing of New Hampshire voters began to hold disproportionate sway in nominating races. The national media took note and the “popularity contest” (more than delegate commitments) became the mark of success in other states as well. Ever since, candidates have followed in the footsteps of Dwight Eisenhower, Estes Kefauver, and John F. Kennedy. Read here.

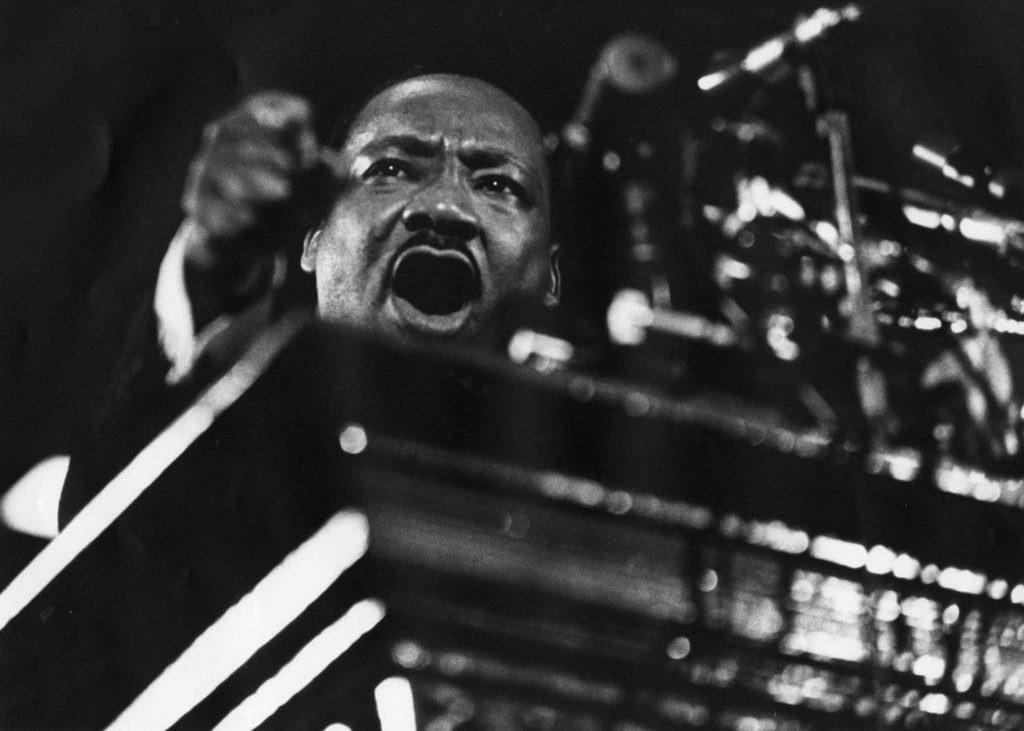

“Martin Luther King’s Activism Points to a Way Forward for the Left – But Not How We Might Imagine,” Washington Post, January 15, 2018.

Today, we pause to remember the life and work of Martin Luther King Jr. But which King will we remember? Undoubtedly, most Americans will reflect on King’s role in civil rights. As some historians remind us, we should also remember his participation in the antiwar movement and his campaign against economic injustice. There is yet another Martin Luther King that we often forget — one who takes us back to the religious ferment of the 1960s.

As a young Baptist pastor, King was steeped in black prophetic religion. To the cause of racial justice he brought a rhetoric and religious vision that captured African Americans’ centuries-long struggle for equality, a faith that was always in conversation with the evils of the world. Read here.

“Martin Luther Changed Christianity 500 Years Ago – It Changed Again in the 1960s,” Time.com, October 30, 2017.

It was 500 years ago, Oct. 31, 1517 in the old Julian Calendar, that Martin Luther submitted his Ninety-Five Theses to Roman Catholic authorities. Nearly all of American history bears the imprint of that act of protest. Luther’s challenge, the protection he obtained, and the reformers he inspired laid the foundation for the Protestant establishments of colonial America.

Vigorous anti-Catholic rhetoric and occasional violence under the Early Republic indicate that lofty Enlightenment ideals checked longstanding prejudice only to a point. Rather, the limited ecumenical impulses of the country’s formative decades cemented the United States as a “pan-Protestant enterprise.” Beginning in the 1840s, mass immigration of Catholic groups reinforced the foreign and allegedly un-American character of the Catholic faith. Read here.

“JFK at 100,” History News Network, March 12, 2017.

One hundred years ago, the United States went to war. On April 6, 1917, Congress responded to the notorious Zimmerman Telegram and continued depredations on merchant ships by adopting a resolution of war against Germany. Thus began the march to a Western victory on the battlefields of Europe; thus, also, opened a dark chapter in this country’s history. New agencies and new legislation severely curtailed civil liberties and contributed to a repressive cultural regime.

Such was the context in which John F. Kennedy entered the world, on May 29, 1917. As we reach the hundredth year of his birth, it seems natural, as with all such anniversaries, to pause and consider what remains of Kennedy’s life and legacy. With Kennedy more than any other American president, the exercise proves daunting. Few Americans have marked our collective consciousness so powerfully relative to the time they spent in the national spotlight, but it is no small task to assert the broader significance of Kennedy’s thousand days in office in the modern American history classroom. Read here.

“The Making of a Presidential Soul,” Process: Blog of the Organization of American Historians, October 20, 2016.

That this is an unprecedented presidential election campaign is already a cliché. The country has never seen the likes of the two leading contenders—and in one case, anything quite like the candidate’s words and deeds. But most remarkable of all, considering the arc of American politics in the last four decades, is the limited attention either candidate has received from the perspective of his or her faith.

Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have apparently sought to relegate their religious identities to a personal sphere, inconsequential to their politics or to the voting public. Both have proven reluctant to speak on their faith, with small, tentative exceptions (see here and here, for instance). Read here.