No history as rich and complex as that of Franco-Americans can be reduced to small vignettes. But what would a survey of iconic Franco-American documents and moments—perhaps destined to a neophyte—would look like? As a fun experiment, I propose the following. It is hoped that these texts (some well-known, some less so) will encourage readers to explore new dimensions of French Canadians’ North American journey.

Udny Hay and the Canadian Refugees (1786)

American Patriots’ invasion of the Province of Quebec, in the early stages of the Revolutionary War, was a failure. Though it held Montreal for over six months, the Continental Army could not count on a groundswell of radical fervor among French Canadians. By the time delegates in Philadelphia signed the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, British forces again controlled the St. Lawrence River valley.

Yet, in that time, hundreds of French Canadians had joined the ranks of the Continental Army. While their exiled families lived in Albany and Fishkill, New York, these men continued to serve the revolutionary cause—from the upper Connecticut River to Yorktown. When the war ended, still unwelcome in Quebec, these soldiers and officers faced uncertain prospects, not least because their pay and pensions were still in arrears.

New York State intervened—to the relief of the Congressional Congress, which was still providing rations to the indigent refugees. Arrangements were made to relocate French Canadians temporarily living in New York City and along the Hudson in the northern part of the state. A coordinator was found in the person of Udny Hay, a former Quebec City lumber merchant who had done his part for the Continental Army.

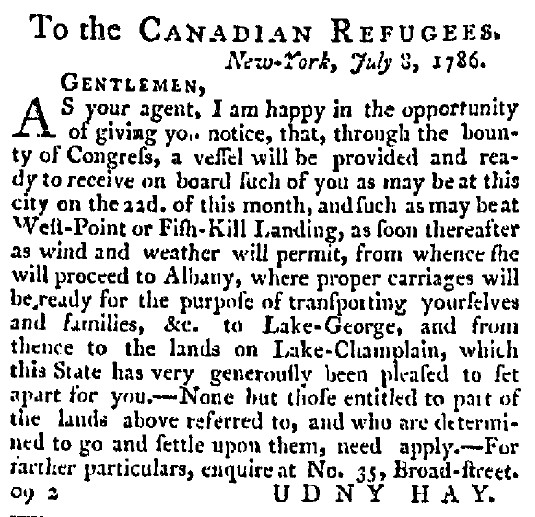

In a New York newspaper, Hay advertised Congress’s willingness to supply a vessel and plans for an expedition that would take the refugees and their goods to the shores of Lake Champlain. Although the French-Canadian settlement in present-day Clinton County held, the colonists faced every conceivable privation for years, adding to the physical and mental wounds of the war.

Hay’s public notice, which appeared in Loudon’s New-York Packet in July 1786, is not the earliest document providing evidence of French Canadians’ presence on U.S. soil. Yet it is significant as one of the first hints of an attempt to build permanent communities in this new country.

The Impending Crisis of Lower Canada (1849)

It is tempting to begin the story of French-Canadian immigration to the United States in the years following the Civil War. Most national parishes in the big industrial centers of New England were not established until the second half of the 1860s. In reality, though sources are more limited for the earlier period, there is still ample evidence that a massive wave of emigration from Lower Canada (now Quebec) was under way in the 1840s.

In the 1830s, the Montreal Gazette remarked on farmers’ sons from the Richelieu River valley seeking their fortunes—or merely a living—in the U.S. Midwest. But it is the next decade that showed that all was not well in the kingdom of Denmark colony of Lower Canada. In 1849, a parliamentary committee chaired by a future premier of Quebec reported its findings and the prognosis was far from rosy.

Every year, Canadian men left the colony to pursue seasonal work in the States. Most returned, but the number who stayed on U.S. soil was growing. The committee estimated that 20,000 Canadians had left their native soil in the prior five years. Without immediate measures on the part of the government, this migratory phenomenon would become an utter disaster for Lower Canada.

The colony, it seemed, needed better roads to promote internal trade and encourage domestic colonization. The government ought to act against speculation and the abusive rents and obligations imposed by landowners. In addition, some public funds should be allocated to promote better agricultural practices.

A similar report issued eight years later reveals how little had been done in that time. In a sense, the report of 1849 anticipated the sustained nature of emigration through the next half-century. It also foreshadowed the limits of government intervention in the same period.

There is cause to be critical of government officials of the day for their contempt and their apparent inaction. On the other hand, the British colonies formed a small economy largely focused on resource extraction and with limited access to capital. The Great Republic was quite the opposite, and the opportunities that Canadian families found south of the border attested to structural forces that could not be overcome by building roads into the wilds of northern Quebec.

Romance in Unromantic Times (1878)

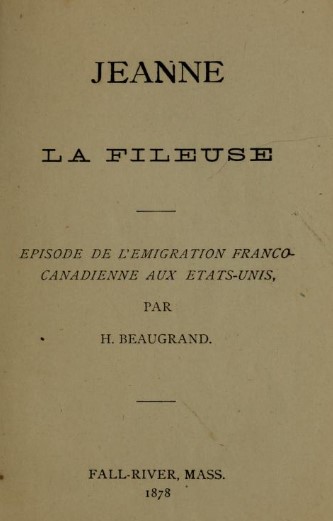

Jeanne loved Pierre, Pierre loved Jeanne. Classic love story. It may be too much to say that in Jeanne la Fileuse (1878), Honoré Beaugrand authored Quebec’s own “Romeo and Juliet.” This was no less an influential novel. Beaugrand depicted a lumber trade—then in decline—that enabled young men like Pierre Montépel to complement farm earnings. He also appealed to French Canadians’ historical memory: Pierre and Jeanne were initially kept apart by family rivalries inherited from the Rebellions of 1837-1838.

Beaugrand shared some of the reasons that were leading whole families, whole communities onto U.S. soil. Through the novel, he put a face to the diaspora and he humanized emigrants who were too often the object of elites’ contempt. Jeanne, having lost her father, followed a local family to Fall River, Massachusetts. Pierre sought to join her after another season in the logging camps; if they were kept apart in the end, it was due to the nature of industrial work in the late nineteenth century.

Beaugrand’s own life had spanned these two different economic and cultural universes; he penned Jeanne la Fileuse while an editor in Fall River and could claim to write with some authority. But he was concerned with more than verisimilitude. He interrupted the plot by commenting at length on the failures of government officials in Quebec City and Ottawa.

Instead of tending to the difficult business of fostering agricultural and industrial progress in Quebec, politicians led by George-Etienne Cartier had preferred to build a new political union and seek honors and titles in London. Beaugrand took them to task. Their own failures made the contempt they expressed for the “rabble” settling in the U.S. all the worse.

A classic love story, sure—but also a scathing attack on Canada’s conservative establishment.

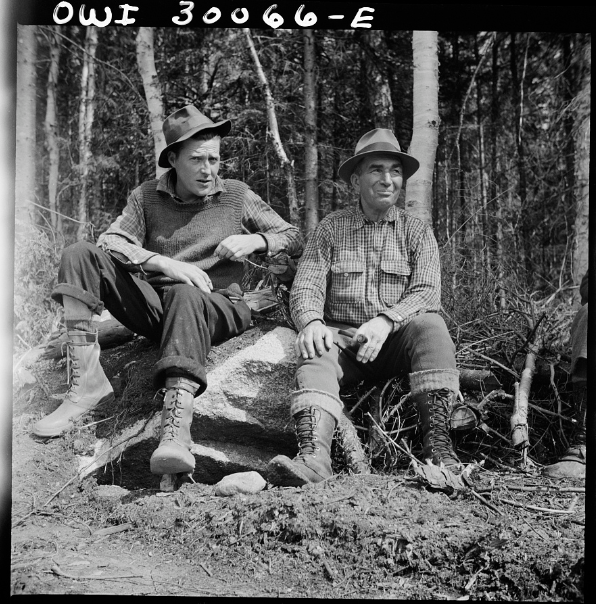

The Canadians and the Colonel (1881)

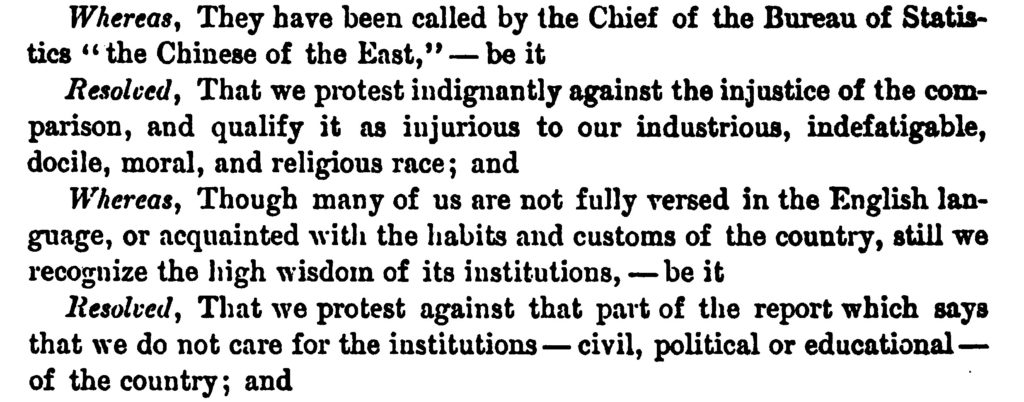

Among Franco-Americans, the Wright report typically needs no introduction. In 1881, Carroll D. Wright, head of the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics, lent his name to a report on working conditions in the Bay State. The report contained all sorts of assertions concerning French-Canadian immigrants—although no assertions by French Canadians. The most dubious statement, which instantly caused outrage in the Little Canadas, was Wright’s claim that these immigrants were “the Chinese of the Eastern States,” due to their transient presence, work habits, values, and foreign connections.

The report of 1881 was a small glimpse of the nativism (Anglo-Saxon and Irish) that Franco-Americans would encounter and endure for decades—as well as hinting at contemporary racial dynamics. On the other hand, it provided evidence of organized community life, political awareness, a sense of shared purpose, and the rise of a lay elite among Franco-Americans. The protests were vigorous and in fact forced Wright to convene hearings in the fall of 1881. Editor Ferdinand Gagnon and attorney Hugo Dubuque led the proceedings on behalf of their compatriots and left Wright with a far different impression that the image offered by his earlier Irish informants.

We know, in retrospect, that Gagnon, Dubuque, et al. overstated their case. They emphasized the progress of naturalization, the increasingly settled nature of immigrants, their commitment to their adoptive country, and so forth. Even as it applied to elites, their case was a stretch as of 1881. Yet, by their very presence, they challenged misconceptions and found support that evinced the existence of something called Franco-America.

Politics would tend to split Franco-Americans over time. Still, at the dawn of the 1880s, increased communication between Little Canadas offered hopes of a shared destiny and enabled elites to rehearse for the many more ethnic controversies yet to come.

The Age of Demographic Deluge (1891)

It was no accident that French-Canadian immigrants became the target of renewed attention—and suspicion—on the part of “old-stock” (predominantly native-born, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant) Americans in the early 1890s. The reason was a Quebec prelate named Edouard Hamon, who wrote an impressive tome of over 400 pages on Franco-American life. When his book, Les Canadiens français de la Nouvelle-Angleterre, appeared in 1891, it raised new concerns about the economic and political fate of the Great Republic in the era of mass immigration.

It must have seemed as though Franco-Americans couldn’t win. Colonel Wright had assailed them partly because they seemed unwilling to put down roots and formally commit to American life. Hamon showed that there were now 400,000 French Canadians living in the seven states of the U.S. Northeast. He faithfully recorded the names of all ethnic parishes in New England and depicted the many cultural and religious institutions the Canadians had established on American soil. These immigrants weren’t taking their money and running—they were taking over the country!

Hamon’s providential vision hinted at just such an eventuality; it lent credence to nativist fears and nourished debates for the better part of a decade. It encouraged calls for compulsory public education and may have justified efforts to restrict access to the ballot in Maine in the early 1890s. With the attention the book received, Franco-Americans may have been victims of Hamon’s success.

From a present-day standpoint, the book is an invaluable resource for researchers seeking to better understand the state of Franco-America at the turn of the 1890s. Though Hamon never settled permanently in the United States, and some errors crept into his work, Les Canadiens français de la Nouvelle-Angleterre still stands nearly unequaled as a contemporary glimpse into the rich and diverse “national” activities of the expatriates.

The series on significant historical Franco-American documents will continue and conclude next week.

Leave a Reply