As previously noted on this blog, it was not the call of political liberty that drew great numbers of French Canadians to the United States in the nineteenth century, but economic opportunity (if not, sometimes, economic necessity). Life in ethnic clusters, in the shadow of gargantuan textile mills, was but a small facet of this economic migration.

Although most “Little Canadas” appeared in New England’s urban landscape in the 1860s and 1870s, it is well-established that the great demographic hemorrhage from French Canada was then already decades-old. The year 1840 has become canonical as a starting point in studies of northeastern Franco-American life. That may be destined to change, as historians continue to look farther and farther back, tracing earlier phases of the diaspora through genealogical and archival research. Readers of this blog will recall that French Canadians formed permanent settlements in northern New York as early as the 1780s. Some turned to Catholic rites and sacraments north of the boundary line and re-established ties to the homeland. Growing commerce along the Champlain–Richelieu axis in the 1790s favoured other kinds of cross-border exchange. Some men evidently found work in northern New York and Vermont in the 1820s and 1830s, but the scale of such migrations—generally temporary—remains obscure. Further research along these lines will enable scholars to determine whether the political exile of Patriotes beginning in 1837 actually spurred emigration that was economically driven.

My research on the early phase of the diaspora and its lasting legacies in rural regions—outside of the Little Canadas—will soon appear online in 49th Parallel, “a peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary e-journal devoted to American and Canadian studies.” I take this opportunity to offer a preview:

In its growing proportions, the effects of the migration were felt at home. The issue entered the realm of public policy. A decade after Durham’s report appeared, the Province of Canada’s legislature formed a committee to study the causes of outmigration from the colony’s eastern section. In their own report, faced with the inescapable attraction of the United States, committee members evinced fatalism:

It would, undoubtedly, be absurd to attempt to prevent or even to discourage those inhabitants of the country who can find more accessible, better cultivated, and cheaper lands elsewhere, from seeking out of their country for that which their country denies them . . . Many Canadian farmers, however, discouraged by the want of roads, the vexations of the large landholders, and sometimes through their own fault and want of perseverance, abandon the lands they have begun to open, and go and hire themselves as labourers to the American farmers.

Estimates from Catholic authorities in Quebec City and Montreal showed that 14,000 people had left the province in the prior five years. The committee thought the number too low and offered instead a figure of 20,000. Without rapid and decisive remedial measures, this movement—believed to have begun in the counties of Huntingdon, bordering on New York State, and Rouville, south of Saint-Hyacinthe, in 1841—threatened to grow ever larger. As a glimpse of its proportions, the committee identified eight distinct occupational and social “classes” held to be contributing to the emigration.

Then, in 1851, twelve Catholic missionaries from the [Eastern] Townships, including a future bishop of Sherbrooke, issued a manifesto with their own set of proposals. […] The missionaries’ advocacy of colonization in the Townships shows that the international border mattered at least in one regard. Migration to the Townships and to the United States was a unitary movement animated by overlapping “push” and “pull” factors. But expatriation to a different polity would deplete French Canadians’ strength and influence in Canada. Emigrants would likely assimilate to a different culture and imbibe the democratic values that seemed (at least for ruling elites) at odds with the British and Catholic experiment along the St. Lawrence. The Townships were the preferred demographic safety valve. […]

The Catholic missionaries’ 1851 appeal was timely—but also in some respects too late. Young men were growing more numerous in distant places, as with Guillaume Larocque, formerly of Saint-Mathias near Chambly, and other Canadians in Addison, along Lake Champlain in southern Vermont. By 1850, the Canadian-born numbered 13.5 percent of all residents of Franklin County, in the north-western corner of the state. Even while accounting for English Canadians, this was no small number. In Burlington, whose population now exceeded 7,500, the ratio was about the same. Through the use of surnames in census returns, Ralph Vicero argued that the lowest likely number of French Canadians in Vermont in 1850 was 12,000; this figure would necessarily omit uncertain cases and exogamous women. There were then 34 towns in Vermont that could boast a population of more than 100 French Canadians.

By looking at the demographic evolution of the immigrant populations of northern New York, Vermont, and Maine, one easily discovers a French-Canadian oikumene—the area occupied by a given people—slowly expanding outwardly from the St. Lawrence River. That process, begun in the earliest days of European settlement, continued throughout the nineteenth century. In the southern part of Lower Canada, agricultural and demographic expansion necessarily encroached upon political borders, which could not contain French Canadians’ search for new economic resources.

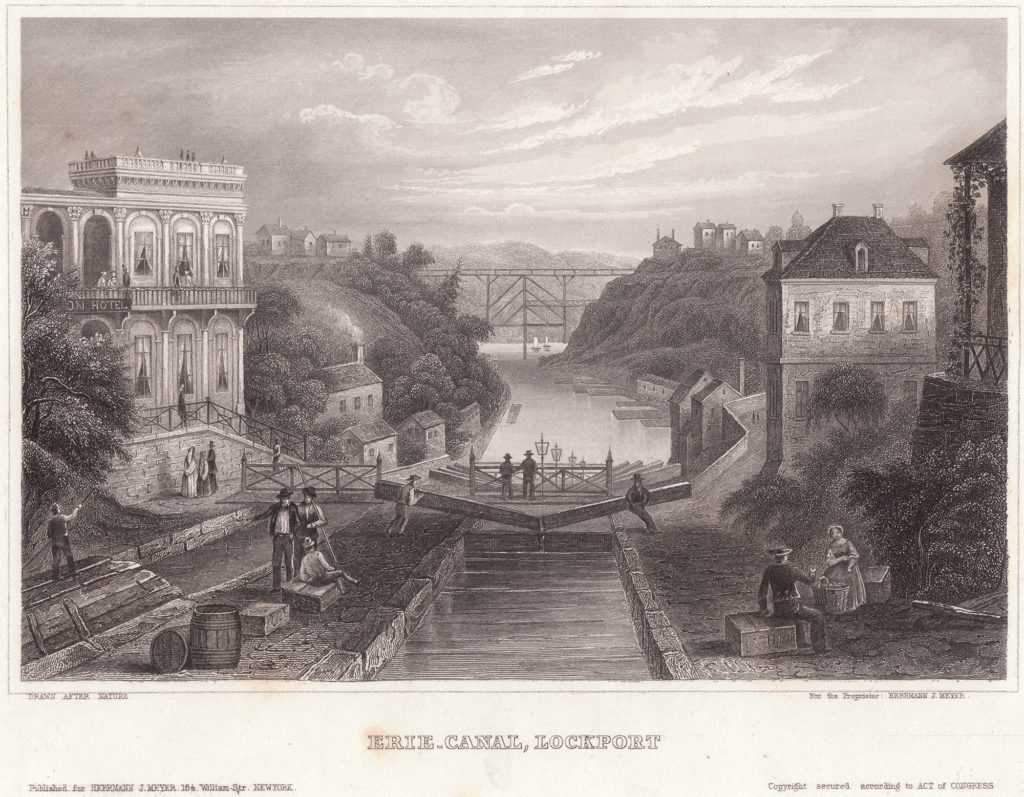

But this straightforward, satisfying process is hardly the entire story. The Canadiens’ horizons were in fact much broader, reflecting opportunities made possible by canals and new commercial networks.

Already, in the spring of 1836, the Montreal Gazette noted that

An immense tide of emigration towards Illinois and Michigan has commenced lately throughout the parishes on the banks of the Richelieu, which promises to continue during the summer. It is limited to [French-] Canadian farmers who are selling off their property, and are bent upon establishing themselves in “the far west.” Three hundred have left St. Johns’ this season with this intention, principally young men, and almost every steamboat that leaves carries off from twenty to thirty. It is said that some Canadians, who have been in Michigan and were successful in their operations, have returned to Lower Canada, and their representations have been of a nature to excite many of their friends to follow their example.

There is enough evidence to suggest that as many as half of all French-Canadian expatriates prior to the U.S. Civil War settled in the Midwest rather than in New York and New England. In a broad hinterland stretching from Louisiana to Wisconsin, this group was preceded by the “human vestiges” of New France, who still constituted a visible portion of residents in certain Midwestern towns. In the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, the development of infrastructure and the rise of a truly national economy in the United States, thanks especially to canals, produced a new wave of French-Canadian immigration to the region. The lumber industry, mines, and transit activities enabled newcomers to pay off debts and complement other income sources.

After 1860, the emergence of the textile industry and its distinctive opportunities in the Northeast would help to overshadow the early phase of the diaspora (indeed, the story of “hinterland Canadians”), which was far more extensive and complex than scholars have typically recognized.

French Canadians’ experience of the United States in these early decades deserves sustained attention, as does native-born Americans’ perception of canadien culture. Henry David Thoreau’s 1845 encounter with a wandering Frenchmen is telling in this regard, but even more so is his 1850 trip to Quebec City. More on that next week.

Leave a Reply